Turkey is held up by many as a beacon of democratic reform. But its youth are frustrated with social and political progress

o Joshua Surtees

o guardian.co.uk, Sunday 1 May 2011 11.00 BST

Turkey – Society – Sacred and Secular Istanbul

Many young Turks are concerned about gay rights, religious freedom, women’s rights and other principles of liberty. Photograph: David Bathgate/Corbis

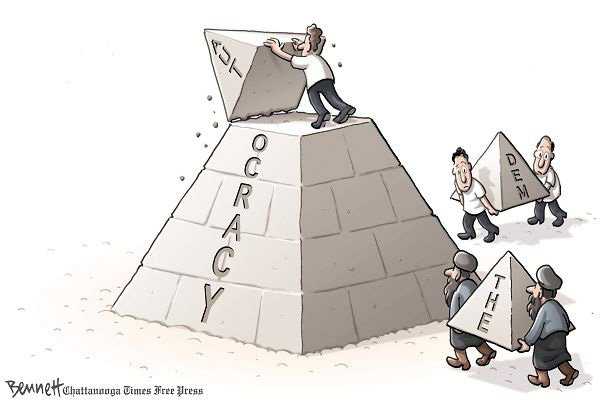

Turkey is often held up as a symbol of progressive modernism – a Muslim democracy on the doorstep of Europe. But the young politically active Turks I spoke to recently in Istanbul feel that social and political freedom is not yet a reality in a country still oppressing its Kurdish population, still tentative on gay rights and still operating compulsory military conscription.

While Turkey is a long way from revolution, the complaints I heard in Istanbul are similar to the frustrations voiced by Arab activists across the Middle East. Those with progressive or liberal inclinations in Turkey are deeply frustrated by a political establishment that does not reflect their values.

Hacer Ocak, a 24-year-old teacher, voted for the Republican People’s party (CHP) at the last elections. Asked about her politics she told me it is not possible to “be political” in Turkey. “You have three options – the current government [Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s conservative Justice and Development party, or AKP], who to me represent the old religious regime; the MHP, who are a militant far-right party; and the CHP, which claims to represent the centre-left but drifts further and further to the right. I voted CHP by a process of elimination.”

Politics in Turkey is extremely divisive. Pelin, 28, a chef, would not tell me who she voted for. “It can destroy friendships,” she said. “Turkey is not a free country. You vote according to whether you are religious or not and Turkey right now is experiencing a huge divide. The young miniskirt wearers hate the burqa wearers and vice versa. The secular people are hugely judgmental of the religious population. Religion is a sensitive subject and cannot be separated from politics.”

When I asked about Turkey’s politically oppressive history in the context of the current situation in the Middle East – crackdowns and detentions in Syria and Yemen – it was interesting to note people were either unwilling to acknowledge Turkey’s dark past or were simply unaware of the brutal actions of the military dictatorship of the 1980s.

I put this down to a deep-seated sense of national pride that is bred through parenting and schooling. There is a strong reluctance in Turkey to criticise the history of their nation. It is this kind of blinkered pride that has seen Turkey steadfastly refusing to recognise or apologise for the Armenian genocide, carried out almost 100 years ago.

As far as the Middle East is concerned, liberal Turks feel that participating in military intervention in Libya is self-interested and hypocritical. Not many people I talked to were willing to discuss the situation in Syria, Libya and Egypt. “We have our own problems to deal with,” said Leyla Buyum, a peace activist. “How can we think of supporting Nato or sending troops to fight while in our own country we have a situation of political repression that isn’t publicised in the Turkish media and is ignored internationally?”

She was referring to the situation in south-eastern Turkey where violence between the Turkish army and Kurdish separatists – the PKK – has continued for decades.

The right to protest is officially sanctioned in Turkey, so protesting is not a danger as it is in Syria. However, it is certainly not as straightforward as in European countries. Police tend to react over-zealously, as seen in the recent use of water cannons on student demonstrators in Ankara.

But what specific issues are there to protest about? There is little overt anti-government sentiment. Erdoğan has successfully taken the reins of the economy, has addressed previously taboo subjects such as the Kurdish question and seems set to be re-elected in June in elections recognised as free and fair.

Military conscription is widely opposed by Turkish youths who feel it represents an archaic militaristic ideal. “Why are we being conscripted? Who are we going to war with?” asked Yavuz Tuncay. “If Turkey really wants to become progressive this has to be abolished. And they must let gay [people] in the army.”

Attitudes towards homosexuality, along with religious freedom, women’s rights and other principles of liberty, are an important touchstone of social democracy, and an issue that Turkey continues to struggle with.

As I left Istanbul I got the sense that Turkey, while having achieved much in the past decade to establish itself as a country intent on progress and social inclusion, still has to deal with issues that its young population has identified as out of sync with democratic ideals.

It is clear that Turks on the street do not align themselves with Europe, the Arab world, the US or anywhere else. Turks feel very independent and fiercely proud of the state created by Atatürk in 1923.

International governments will continue to align themselves with Turkey for strategic purposes and this may further enhance Turkey’s diplomatic status. The assumption that Turkey is a burgeoning or even fully functioning democracy is not entirely accurate yet it is useful for global superpowers such as the US to promote this idea.

The Arab uprisings have reaffirmed Turkey’s strategic importance to the world’s political powers including the US, Israel and the Arab states. The country now occupies a privileged position as the nominal fulcrum of a newly emerging axis in east-west international relations. Turkey has played a central role in Libya and spoken out strongly on Syria. It acts as a base for the US military, a watchdog on Israeli actions and a prospective member of the EU.

The message from within Turkey is that domestic policy should be a higher priority than foreign policy. Many Turks feel that membership of the UN security council and roles in facilitating Nato interventions in external conflicts distract their government from crucial issues at home. They also feel the praise heaped on Turkey from abroad as a model of democratic reform is not yet warranted and may be counterproductive – there is still lots to get right. They hope Erdoğan will continue to give more attention to Turkish citizens’ expectations and social rights as part of a continuing momentum towards a freer and more inclusive society.