By Begüm Burak

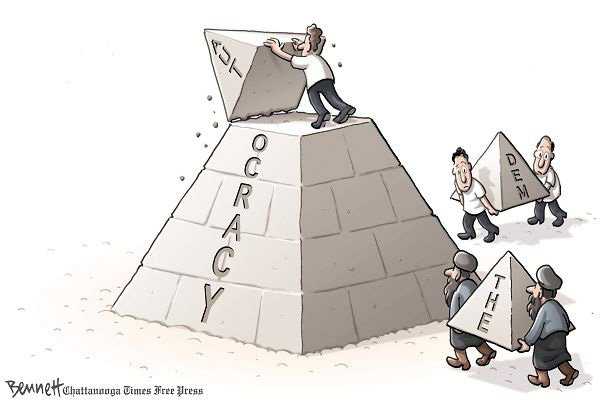

Democracy is the most ideal form of government in the contemporary world. In the post-Cold War era, with the triumph of liberal democracy against Soviet Communism, the importance of democratic norms and principles were emphasized. In fact, the emphasis put upon the virtues of democracy was a product of the Second World War, with the United States’ victory as proof for the necessity of democracy in the new world order.

“…[the] Turkish Army is determined to defend the unitary secular state founded by Ataturk… [and the] Protection of fundamental characteristics of the republic cannot be considered as an intervention in domestic politics.” Isık Kosaner, ex-Chief of the General Staff[1]

Turkey first experienced democracy in the 1800s. Despite the fact that the official history in Turkey states that the parliament was founded in 1920 in Ankara, the truth is a bit different. As a columnist writes:

“Turkey’s [Ottoman Empire’s] first parliament, that is the Meclis-i Mebusan, was founded on March 31, 1877, and it had 115 members. And the parliament founded in 1920 in Ankara was not a new parliament, but a successor to the former one. Almost half of the members of the Meclis-i Mebusan were in the parliament founded in 1920, for example.” [2]

In the world we live in, with the impact of globalisation and the increasing awareness among the people about the developments taking place all over the world, democracy today is not an alien concept. Almost every single person knows that democracy in its simplest terms consists of ‘free and fair elections’. However, this is just a minimal definition of democracy.

Robert Dahl (1982) has offered the most generally accepted listing of what he terms the “procedural minimal” conditions that must be present for modern political democracy (or as he puts it, “polyarchy”) to exist:

1) Control over government decisions about policy is constitutionally vested in elected officials.

2) Elected officials are chosen in frequent and fairly conducted elections in which coercion is comparatively uncommon.

3) Practically all adults have the fight to vote in the election of officials.

4) Practically all adults have the fight to run for elective offices in the government . . . .

5) Citizens have a fight to express themselves without the danger of severe punishment on political matters broadly defined . . . .

6) Citizens have a fight to seek out alternative sources of information. Moreover, alternative sources of information exist and are protected by law.

7) . . . Citizens also have the fight to form relatively independent associations or organizations, including independent political parties and interest groups.

On the other hand, democracy in the Turkish case has generally been a contested concept over which the military elites, bureaucratic class and the politicians generally disagree. The foremost characteristic of Turkish Republic since 1923 has been her secular identity and not a democratic political system. In this context, according to the founders of Turkey among whom Mustafa Kemal Ataturk has had an undisputedly decisive and dominant role, the most important priority was to make Turkey a modern state with a precisely secular(ist) character.

It is obvious that the secularist drive was the most characteristic element of the Kemalist reform movement. Ironically, the way these reforms were implemented has impeded another important aim of the Kemalist modernisation process, that is, realising democracy in the practical sense. Becoming a modern state for the Kemalist elites meant having a Western type of political, social and cultural life (for instance listening to Western music, wearing “modern” Western type of clothes).

But how does democracy become “the only game in town”? The functioning of the economic system, state-religion relations, civil-military relations, the minority rights etc., all have a considerable degree of significance in the establishment of democratic consolidation. Some people argue that Turkey has got an illiberal democracy. An illiberal democracy, as described by Fareed Zakaria, is a political system in which free and fair elections exist, but civil liberties are not fully protected and state power is not limited by liberal principles.[3] Illiberal practices are seen most virulently in the religious sphere and persecution of minority rights. However, it must be noted that these illiberal practices are being challenged today thanks to the EU harmonisation laws and the strengthening of civil society in Turkey.

The Turkish Republic inherited from the Ottoman Empire a strong, centralised, and highly bureaucratic state. Indeed, the “output” structures of the state (the civil service, armed forces, police, and courts) have been so highly institutionalised that this overdevelopment of the state machinery, coupled with the predominance of a “strong-state tradition” in Turkish political culture,[4] impede the emergence of a consolidated democracy.[5]

Despite the EU reform process and other legal and institutional regulations, Turkey still has a long way to go for further democracy. Despite the trial of the coup makers, broadcasting in Kurdish language, the strengthening of a free-market economy and the relative softening of the secularist policies, some pathological state codes constitute a major threat for democratic consolidation.

As Şahin Alpay proposes:

“Reasonable people in Turkey (or abroad) have to face the simple and naked truth: Kemalism, that is, Turkish secular nationalism, is not compatible with liberal and pluralistic democracy. All of Turkey’s major political problems today are the consequence of the forced imposition in accordance with the ‘founding philosophy’ of the republic, that is Kemalism, of a uniform identity onto a religiously and ethnically heterogeneous society”[6]

Last but not the least, I think the most influential factor that is used to block Turkish political progress and harm democracy is the nature of the relationship between the state and religion. As İhsan Yılmaz states:In contemporary Turkey, besides the ruling elites (namely the Justice and Development Party- the AKP[7]), the civil society actors and the bureaucracy occupy undisputedly important roles for making democracy stronger. Because a new, civilian constitution can only be drafted in a pluralistic process through which all the different segments of the society, different ideologies and worldviews reach a common reasoning.

“Laicism was the primary and sacred norm of the country, and for its sake everything else, including democracy, could be sacrificed. Hopefully, this perverted conception of modernity and progress is fading away in Turkey. As we are now talking about crimes against democracy, it is only normal that we start with the main perpetrators of these crimes: coup-loving soldiers.” [8]

[1] The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/aug/29/turkey.islam (August 26, 2011)

[2] http://www.todayszaman.com/columnist-278356-historical-awareness.html (May 10, 2012)

[3] (May 10, 2012)

[4] For further information about political culture in Turkey, please visit (May 10, 2012)

[5] Begüm Burak, “Turkish Political Culture and Democracy: A Forced Marriage or Not?” in Civilacademy, , p. 15 (May 10, 2012)

[6] (May 10, 2012)

[7] A piece regarding AKP, (May 10, 2012)

[8] http://www.todayszaman.com/columnist-278132-democratic-sins-of-the-politicians-in-the-february-28-coup.html (May 10, 2012)