A court ban on the most pro-Western party would be a big mistake.

By Alex Taurel and Shadi Hamid

from the July 24, 2008 edition

Washington – President Bush’s vision of a democratic Middle East was premised in part on the region’s popular Islamist groups reconciling themselves to the give-and-take nature of democracy.

It might make sense then, that the Bush administration would do what it could to support a party that has made such a transformation in Turkey. But it’s not.

Turkey’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), which fashioned itself as the Muslim equivalent of Europe’s Christian Democrats, has stood out by passing a series of unprecedented political reforms as the country’s ruling party.

Yet the Turkish Constitutional Court – bastion of the hard-line secularist old guard – is now threatening to close down the AKP and ban its leading figures, including Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and President Abdullah Gul, from party politics for five years. And the Bush administration, in the face of this impending judicial coup, has chosen to remain indifferent. The consequences could reach beyond a setback to democracy in Turkey and affect the Middle East.

The Constitutional Court will rule as soon as next week on an indictment accusing the AKP of being a “focal point of antisecular activities.”

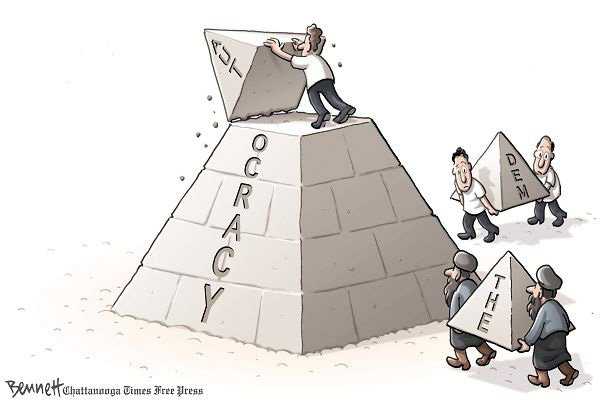

Turkey’s Constitution establishes secularism as an unalterable principle and allows the court to ban parties it deems antisecular. But disbanding a democratically-elected party on such dubious grounds as attempting to lift a controversial ban on wearing head scarves in universities – the crux of the case against the AKP – is not how mature democracies handle divisive issues. Judges should not decide parties’ fates; voters should.

Indeed, voters have flocked to the AKP since its founding by break away reformists within the Islamic movement. The party was elected in 2002 on pledges to preserve secularism and vigorously pursue Turkey’s efforts to join the European Union. It also explicitly disavowed the Islamist label.

The AKP-led government then passed a series of democratic reforms that led Brussels to begin formal accession negotiations with Turkey. Those reforms, together with a booming economy, spurred 47 percent of Turks to vote for the AKP in its landslide 2007 reelection.

To be sure, the AKP’s democratic credentials are hardly perfect. It has been overly cautious in repealing certain restrictions on freedom of speech, and it abruptly lifted the head scarf ban without first initiating a national dialogue.

Yet despite its flaws, the AKP is the most democratically inclined – and somewhat ironically, the most pro-Western – political party on the Turkish scene today. Closing it down would be a mistake.

A ban on a party that nearly half of the country supports could spark violence – which Turkey’s secularist generals might then use as a pretext for a direct military intervention. Regardless, senior EU figures have criticized the closure case and warned that banning the AKP could gravely damage Turkey’s candidacy.

Even more troubling is the message it would send to the rest of the Muslim world – no matter how much Islamists moderate, they won’t be accepted as legitimate participants in the democratic process.

In recent years, mainstream Islamist groups throughout the region – including in Egypt, Jordan, and Morocco – have embraced many of the foundational components of democratic life. Yet their moderation has been met with harsh government repression, or more subtle designs to restrict their political participation.

More is at stake than may initially appear. If the AKP – the most moderate, pro-democratic “Islamist” party in the region today – is disbanded, it will strengthen those Islamists who see violence and confrontation as a surer means to influence political power.

During the past year, a number of Islamist leaders we’ve spoken to in Egypt and Jordan have warned that rank-and-file activists are losing faith in the democratic process, and may soon become attracted to more radical approaches. A ban on the AKP would only make it that much harder for moderates to continue making the case that participating in elections is worthwhile.

Though US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice praises the AKP’s democratization agenda, last month she said, “Obviously, we are not going to get involved in … the current controversy in Turkey about the court case.” Yet moments later she opined, “Sometimes when I’m asked what might democracy look like in the Middle East, I think it might look like Turkey.” It’s difficult to tell if she’s referring to the new, democratizing Turkey of the past five years – or the reactionary Turkey where judges and generals flagrantly overrule the people’s will.

President Bush has one last opportunity to reinvigorate the cause of Middle East democracy. By publicly denouncing the closure case, the administration would signal that the US not only supports Turkish democracy against a dangerous internal assault, but that it is also committed to defending all actors willing to abide by democratic principles in a region that desperately needs more of them.

• Alex Taurel is a research associate at the Project on Middle East Democracy. Shadi Hamid is the director of research there and a research fellow at the American Center for Oriental Research in Amman, Jordan.

Source: The Christian Science Monitor, July 24, 2008