While the Turkish-American community was as usual pre-occupied with arts and entertainment ), during the exact same time the Armenian diaspora was busily continuing to lay the groundwork for an independent Nagorno-Karabağ.

I have attached the complete text of former Armenian Foreign Minister Vartan Oskanian’s April 12, 2018 speech at the Harvard University Law School below. Turks as well as Azeris should pay heed since it not only mentions Nagorno-Karabağ but refers to “Kurdistan” as well and quite obviously the thesis of “Self-Determination” Oskanian was attempting to make would apply in both cases if one were to subscribe to it.

Enis Pınar

Kimden: USC Institute of Armenian Studies [mailto:armenian=Yerine USC Institute of Armenian Studies

Tarih: Thursday, April 5, 2018 7:06 PM

Konu: Self-Determination Under International Law: With Vartan Oskanian

April 12 – Harvard Law School Pound Hall – 12-1pm

After a series of lectures at University of Southern California, in a class called IN PURSUIT OF INDEPENDENCE, Vartan Oskanian, former Foreign Minister of Armenia, will be heading to Harvard University for a lecture on a matter that is at the crux of Armenia’s existence and future development.

Vartan Oskanian served as Armenia’s foreign minister from 1998 to 2008 and is the founder of Civilitas Foundation, a Yerevan-based education and advocacy NGO. He is a graduate of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. Mr. Oskanian was a visiting assistant professor at the American University of Armenia and currently a visiting lecturer at the University of Southern California and Tufts University.

The talk will be moderated by Anna Crowe, Lecturer on Law and Clinical Instructor at the Human Rights Program of Harvard Law School.

Organized by:

West Coast Law Students Association

Middle East Law Students Association

Harvard International Law Journal

Harvard European Law Association

Sponsored by the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research – NAASR

Former Foreign Minister Vartan Oskanian Delivers Talk on Self-Determination at Harvard Law School (Full Transcript)

April 16, 2018

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (A.W.)—Armenia’s Former Minister of Foreign Affairs Vartan Oskanian delivered a talk at Harvard Law School titled “Self-Determination Under International Law: The Cases of Kosovo and Nagorno-Karabagh,” on April 12.

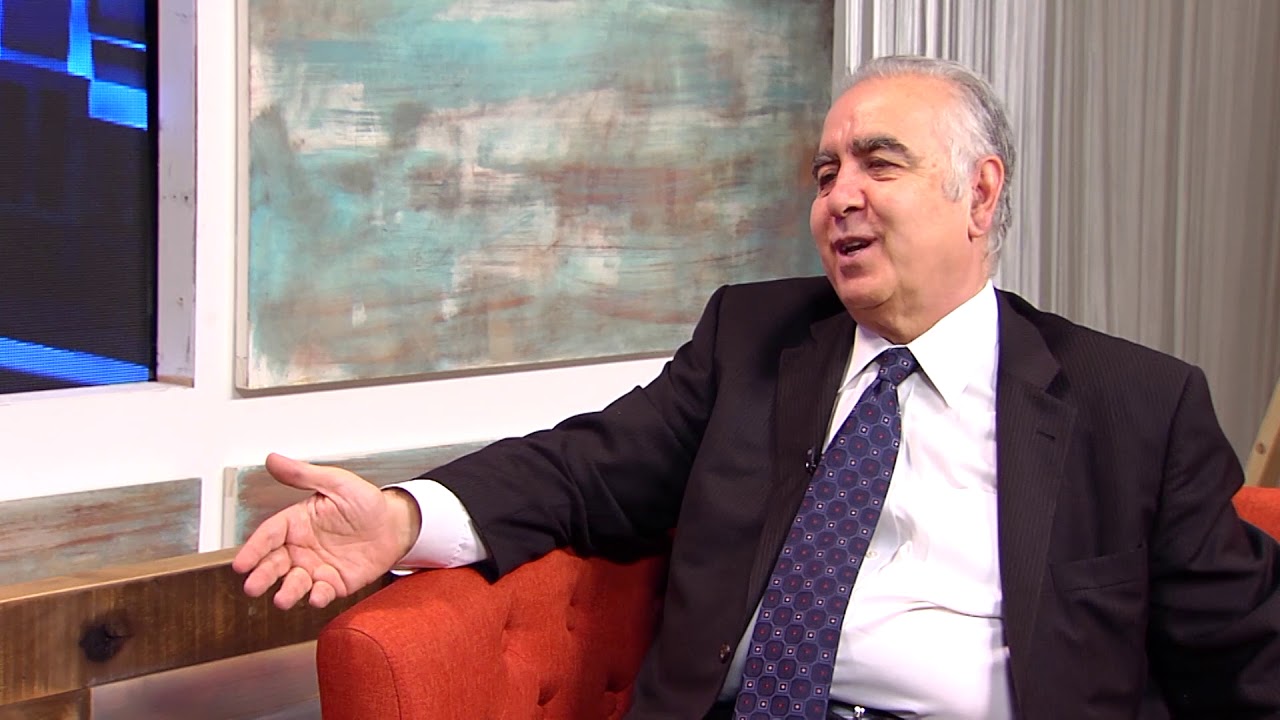

Oskanian speaking at Harvard Law School (Photo: Harout Ekmanian)

The talk was organized by the joint efforts of Harvard Law International Journal, Harvard West Coast Law Students Association, Harvard European Law Association, and the Harvard Middle Eastern Law Students Association. It was moderated Anna Crowe, Lecturer on Law and Clinical Instructor at the Human Rights Program of Harvard Law School, and sponsored by the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (NAASR).

Oskanian addressed the right of self-determination in the cases of Kosovo and Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabagh) through the dual lenses of international law and global politics, as well as the origins and the evolution of the right for self-determination, and what the sources of international law say about it. He also touched upon the currently active self-determination movements, including Kurdish and Catalan referenda, and assessed the impact and relevance to these movements.

Before his talk at Harvard Law School, Oskanian delivered a series of lectures at the University of Southern California in a class called “In Pursuit of Independence.” Next fall, he will teach a course at Tisch College of Civic Life of Tufts University called “Special Topics in International Relations: The Politics of Self-Determination and Secession.”

Below is the full transcript of Oskanian’s talk at Harvard Law School.

‘Self-Determination Under International Law: The Cases of Kosovo and Nagorno-Karabagh’

Vartan Oskanian at Harvard Law School – April 12, 2018

Thank you for the invitation. I truly appreciate this opportunity.

Although my theme today is international law and, in particular, the law of self-determination and secession, let me reinforce the fact that I am not an international lawyer; have never argued or judged a case in international courts, nor represented any government in judicial proceedings. I am simply a practitioner of diplomacy.

My diplomatic and ten-year tenure as foreign minister of Armenia, and as Armenia’s chief negotiator for Nagorno-Karabagh conflict with Azerbaijan, propelled me to the forefront of diplomatic activities of one of the most pressing and trying global transformations: that of the emergence of great number of new independent states at the end of the Cold War and subsequently a parade of sub-state self-determination claims each with unforeseen consequences.

Nagorno-Karabagh was, and still is, one of them. So was Kosovo together with many others. This period coincided also with the emergence of many other secessionist movements outside the context of the unraveling of the USSR and Yugoslavia—South Sudan, Timor L’este, and later on Quebec, Scotland, and more recently Kurdistan and Catalonia.

If you are pursuing a self-determination claim, you need to pose and seek answers to two fundamental questions: First, is there enforceable international law or its all politics? Can we speak of international law as a coherent activity? Second, is there a law on self-determination and secession that minority groups can rely on to support their claims? The answer to these questions depends on who you ask, what the circumstances are, and the geopolitical interests of the rich and powerful.

There is a common belief in diplomatic and political circles that there are two kinds of international legal order. They concede the existence of law in areas such as trade, telecommunication or civil aviation while at the same time dismissing as mere unenforceable aspirations, laws on the use of force, human rights, sovereignty and self-determination. This duality of international law goes back, at least to early 1920s, to Hans Morgenthau, one of the founders of international relations and a realist in his outlook, who contrasted two different types of international law, a “functional international law” based on ‘permanent or stable interests’ and ‘political international law’ that was opportunistic, indeterminate and aspirational.

Before I move to the second question, whether there is a law on self-determination and secession that minority groups can rely on to support their claim, let me briefly talk about the sources of international law.

Unlike national law which is made in the legislature, international law creation is much more complex, and has a multitude of sources.

There are several sources of international law. One is international treaties and conventions; the second is international custom and the general principles of law, as evidence of a general practice accepted as law; and third, the subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law, such as judicial decision and the teachings of the most highly qualified publicists. This also includes the United Nations General Assembly resolutions. For example, Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), Declaration on the Inadmissibility of Intervention in the Domestic Affairs of States and the Protection of their Sovereignty (1965), Declaration on Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation among States (1970), etc., are all treated as strong evidence of rules of customary international law.

The law of self-determination has its roots, not in treaties, that would have made things much simpler, but in the customs, general principles of law and the subsidiary means, such as UN General Assembly declarations and resolutions, judicial decisions and the writings of qualified publicist. And that is why the right of self-determination is more elusive in the context of law. And if we add to this that the issue of self-determination falls also in the domain of Morganthau’s “political international law,” it becomes even clearer the complexities associated with it and the divide it creates between the opponents and proponents of the right for self-determination..

The principle of self-determination developed as political idea and corollary to growing ethnic and linguistic political demands in the 18th and 19th centuries. Those times equating a nation with a homogeneous populace was very common. It gained prominence when President Wilson became the most public advocate of self-determination as a guiding principle in the post-war period, but was never fully implemented as the allies were guided mostly by political considerations to buttress Germany and the Soviet Union.

It was only after the founding of the UNin 1945 that the principle of self-determination began a gradual shift to a more enforceable right to freedom from colonial rule. The UN Charter, of course, explicitly refers in its Article 2(1) to the self-determination of peoples, but it is its Chapters XI and XII on non-self-governing and trust territories that gave the principle its more enforceable character, eventually transforming self-determination from principle to right.

During the 1950s and 1960s The UN General Assembly passed several resolutions granting independence to colonial territories and countries. All of them had two things in common; the focus was on territory rather than people and had a “safeguard clause” stressing the preservation of territorial integrity, by stating that “any attempt aimed at the partial or total disruption of the national unity and the territorial integrity of a country is incompatible with the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations.”

In 1966, the adoption of two international human rights covenants—one on economic, social, and cultural rights, the other on civil and political rights—raised, for the first time, true possibility that international law might provide some support for other form of self-determination. Both covenants state that “all peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of the right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.”

And in 1970, the General Assembly unanimously approved a landmark resolution, known as the “Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation among States.” This Declaration was unique and groundbreaking for two reasons: one, for its expansion of the scope of the right of self-determination arguing that it be implemented through the “establishment of a sovereign and independent State, the free association with an independent State or the emergence into any other political status freely determined by a people;” two, while like the resolutions that preceded it, emphasized the preservation of territorial integrity, for containing a qualification specifying that the protection of territorial integrity applies to states “possessed of a government representing the whole people belonging to the territory without distinction as to race, creed or color.”

There is no consensus among scholars or governments on how this qualification affects the relationship between the right of self-determination and the principle of territorial integrity. Some have argued that the principle of self-determination can be accorded priority over the principle of territorial integrity if a state is not possessed of a government representing the whole people. Others, of course, disagree.

In my view, what has preceded and followed this particular qualification established in the “Friendly Relations” resolution, does provide bases to argue for the existence of what came to be known in the parlance of international law as the right for “remedial secession.” One may go back to the early 1920s to see evidence of this norm in the Aaland Island case, when non of this trajectory of the evolution of the self-determination law, whether in the context of decolonization or outside of it, ever existed.. And the juxtaposition of the natural law reasoning with the positivist tradition renders this notion even a more credible and applicable norm of international law.

Aaland Islands, located in the Baltic Sea between Sweden and Finland, were under Swedish control from 1157 to 1809 and retained their Swedish linguistic, cultural heritage thereafter. After Sweden’s defeat by Russia in 1809, Finland, including Aaland, was ceded to Russia, and Finland became an autonomous Grand Duchy within the Russian Empire. In 1917, shortly after the March Russian Revolution, Finland declared its independence in December 1917. Riding the Wilsonian self-determination wave, the Swedish population of Aaland opted for unification with Sweden causing serious turmoil and instability in the region. To address the issue, the League of Nations appointed two bodies of experts, each with a little different task, to examine the question.

Their decision was negative, and they basically argued that granting them their wish “it would be to uphold a theory incompatible with the very idea of the State as a territorial and political unity.” However, the Commission did suggest that under extreme oppression, self-determination by Aaland citizens might be possible. “The separation of a minority from the state of which it forms a part and its incorporation in another state can only be considered as an altogether exceptional solution, a last resort when the state lacks the will or the power to enact and apply just and effective guarantees.” This is a clear articulation for the right for remedial secession

In 1993, one of the rounds of Nagorno-Karabagh talks was organized in Mariehamn, the capital of Aaland Islands in Finland. Finland, at that time was, along with Russia, the co-chair of the Minsk Group process on Nagorno-Karabagh. Their purpose was to demonstrate to all participants, Armenian and Azeri, but particularly for the Nagorno-Karabagh representatives, how workable it is Aaland’s autonomous all Swede minority status within Finland. We stayed on the Island for about a week, and along our daily regular talks, were given tours to governmental institutions, had talks with officials and regular citizens. Clearly, it was a happy Swedish island, and the Swedish minority was the master of its faith and future. The only reminder of Finnish sovereignty over the Island were the Finnish flags on top of government buildings. As we were wrapping up the talks and the trip in general, the head of Nagorno-Karabagh delegation made an astounding statement: “We have truly liked what we have seen here, and I can officially declare that we will accept a similar autonomous status for Nagorno-Karabagh.” Then came the punchline: “but within Finland; not Azerbaijan.” We all laughed. But this is very telling and goes directly to heart of the notion of “remedial secession.”

Another example of institutional practice that supports the idea of secession as a remedial right was the Canadian Supreme Court interpretation of self-determination and secession in its 1996 landmark decision. The Federal Government of Canada asked the court for an advisory opinion on several aspects of Quebec separation, hoping that the result might discourage Quebecers from voting for it. The Court’s opinion was that “a right to secession only arises under the principle of self-determination of peoples at international law where a people is governed as part of a colonial empire, where a people is subject to alien subjugation, domination or exploitation; and possibly where a people is denied any meaningful exercise of its right to self-determination within the state of which it forms part.”

Interestingly, the Canadian Supreme Court in its decision also introduced a caveat, stating that if a referendum found in favor of independence, the rest of Canada “would have no basis to deny the right of the government of Quebec to pursue secession.” In my view, this statement has extremely consequential effect on the political aspects of the law of self-determination, and I will ask you to hold on to this thought until I come back to it towards the end of my talk.

Then, of course, there is the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) Advisory Opinion on Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence. As you know, on February 2008 Kosovo unilaterally declared its independence. In October of the same year, the General Assembly decided to ask the Court to render an advisory opinion on the following question: “Is the unilateral Declaration of Independence by the Provisional Institutions of Self-Government of Kosovo in accordance with international law?” The court in its advisory opinion said that the practice of states both in the context of decolonization and outside of it “does not point to the emergence in international law of a new rule prohibiting the making of a declaration of independence in such cases.” That means the international law neither forbids nor supports secession. It is simply agnostic about it. Thus, the ICJ itself, in his opinion, adopted a very narrow approach, not providing any guidance regarding the contemporary scope of self-determination.

However, the value of the ICJ’s Advisory Opinion is not in its opinion per se, rather in its explanatory notes and the positions expressed by the more than forty or so states in their written and oral presentations to the court.

There are three important takeaways from all this which, in my view, reaffirm certain understandings that are critical in establishing positions regarding the right of self-determination in international law.

One is that as several participants in their arguments before the court contended that a prohibition of unilateral declaration of independence is implicit in the principle of territorial integrity, the court responded that the scope of the principle of territorial integrity is confined to the sphere of relations between states, citing the UN charter, the Friendly Relations resolution and OSCE Helsinki Final Act. Indeed, Article two of the UN Charter provides that “all members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of many State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.”

Two is, that when several participants invoked resolutions of Security Council condemning particular declarations of independence, such as Southern Rhodesia (1965), Northern Cyprus (1983) and Respublika Srpska (1992), the court responded that the illegality attached to those declarations of independence stemmed not from the unilateral character of the declarations as such, but from the fact that they were, or would have been, connected with the unlawful use of force or other egregious violations of norm of general international law.

Three is, that the Court simply noted—taking no position—that “radically different views” were expressed on the question of whether a right of remedial secession exists and, if so, in what circumstances and if those circumstances were present in Kosovo.

This last point is hugely important because the bigger question and the more controversial part of the right of self-determination is not as much whether there is a right for remedial secession in international law. There is. Rather, the circumstances which one may maintain that would give rise to right to remedial secession are sufficiently present in any particular case.

The determination of the presence of circumstances is more of a political decision rather than a legal judgment, and it is the very critical component around which law and politics intertwine. However, as a result of the new developments in international law after the end of the Cold War, now in addition to unlawful use of military force, oppression and atrocities committed, the protection of minority rights and entitlement to democratic government are key elements in determining the circumstances that may give rise to the right for remedial secession.

Kosovo and Nagorno-Karabagh are very similar yet different. Both are geographically separate and ethnically, religiously distinct from the mother state. Both neighbor a country of their kin. Both have been disputed territories at one point in their history, both had autonomous status within their mother states during the Cold War, and their autonomous status revoked at one point. Both subjected to severe oppression and atrocities. The key difference is geopolitical.. Kosovo is at the heart of Europe and has history of triggering and implicating others in a broader conflict and jeopardize Europe’s and world’s peace and security. Hence the extraordinary global attention and the international community’s immediate and continued involvement in providing an early solution. Karabagh has taken a different path but gone through similar process. If ever Nagorno-Karabagh case goes to ICJ, the nature and content of the arguments will not be much different from Kosovo’s case.

And finally let me introduce two overbearing political developments which, in my view, complements the existing legal framework in support of the right of self-determination and secession.

First is that earlier, speaking of Canada’s Supreme Court decision on Quebec’s referendum I said hold on to the thought that the justices said that if a referendum found in favor of independence, the rest of Canada “would have no basis to deny the right of the government of Quebec to pursue secession.” This naturally means that political negotiations would have to follow to define the terms under which Quebec would gain independence, should it maintain that goal. This, clearly is a political decision; a recommendation of sort to reach a peaceful resolution.

This also implies that references to the state’s own constitution as a non-negotiable bar, as is being employed in case of Kurdistan, Catalonia and also Nagorno-Karabagh, to any concessions or even negotiations do not represent good faith, and cannot be justification for use of force to suppress the movement.

Second is that since the end of the Cold War, there has been at least a dozen of peace processes related to ethnic conflicts mediated by third parties and mandated by international organizations, where in their proposed solutions granting satisfaction to the aspirations of the minority groups have been the norm rather than the exception. Some have been fully implemented, others failed due to different circumstances and few others are still work in progress.

But the fact is that after lengthy and arduous processes, the mediators, in all those cases where the historical, legal and military realities have tilted the balance on the self-determination side, seem to have always favored to arrive to the inevitable sooner than later. The Road Map for Peace for the Israeli/Palestinian conflict; the Good Friday Accord for Northern Ireland; the Machakos Protocol for Sudan; Ahtisaari plan and Security Council Resolution for Kosovo; the Baker Peace Plan for the Western Sahara, the Dayton Accords for Bosnia, UNSC Resolution 1272 for East Timor; the Comprehensive Agreement for Bougainville; the New Constitution for the Union of Serbia and Montenegro, the Madrid Principles for Nagorno-Karabagh.

All self-determination or secessionist movements are, in essence and at heart, ethnic conflicts. They originate in history; get litigated, adjudicated, argued and negotiated in international organizations; always have their military component, since one or the other side and, most of the time, both sides use force against each other to achieve their goals; and finally, if they ever get resolved, are resolved at the political level. It is true that at the end of day it is the politics that has the final word. But history, law, military outcome and geopolitical realities on the ground, are all critical in determining the fate of a particular claim, and inevitably forces the political hand even of the most ardent opponents, including the mother states, of the right of self-determination and secession.

1 Comment

Dave says:

Dave says:

April 17, 2018 at 4:34 pm

And so, mr. Oskanian, what is Artsakh’s case specifically?

What are the arguments in its favor?

Let’s admit that, ultimately, it depends on politics and military strength.