Turkey’s migrant deal with Europe may collapse under post-coup attempt crackdown

People wave Turkish national flags as they gather this month at Kizilay Democracy Square in Ankara during a rally against a failed military coup on July 15. (Adem Altan/AFP/Getty Images)

By Michael Birnbaum and Erin Cunningham

Europe

August 23 at 3:00 AM

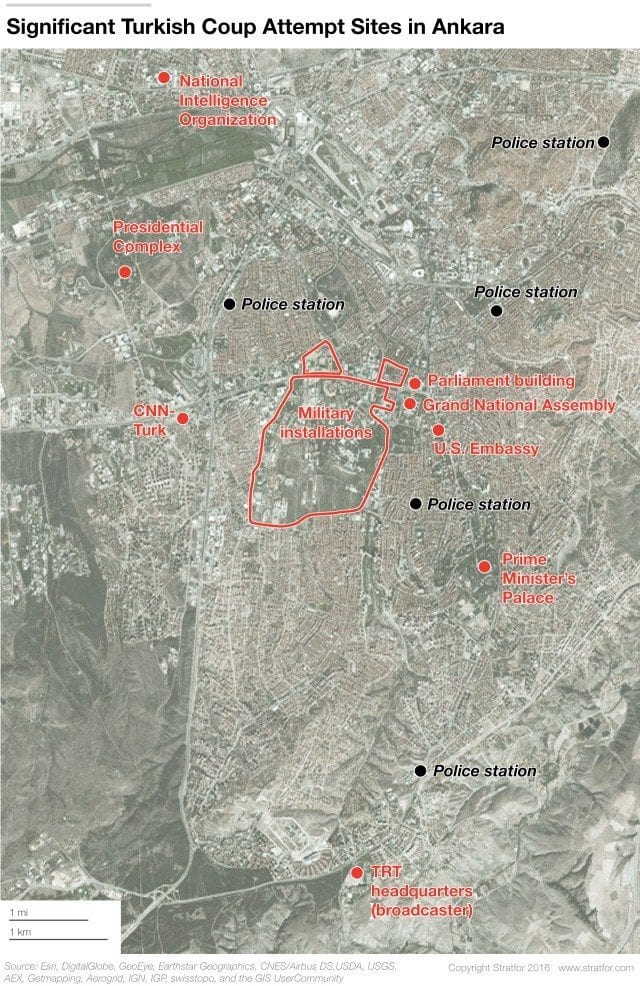

BRUSSELS — The landmark agreement that halted a torrent of migrants flowing from Turkey into Europe is nearing collapse in the wake of the failed Turkish coup and the subsequent nationwide crackdown.

Turkish and European leaders are threatening to abandon the deal — the Europeans because they say they are worried about widespread human rights abuses, the Turks because of European reluctance to fulfill a promise to drop visa restrictions for Turkish nationals.

Now, even as it detains tens of thousands of people in response to the coup attempt, Turkey has given the European Union an October deadline over the visa pledge — or it will walk away from its commitment to stem the flow.

An end to the agreement, which came after more than a million migrants and refugees entered in Europe in 2015, would mark another blow to the contentious relationship between the E.U. and Turkey, which is petitioning to join the bloc. It could also result in a fresh surge of asylum seekers traveling from Turkey, which would confront E.U. leaders with a new humanitarian and political dilemma after a relatively quiet spring and summer.

Austrian Chancellor Christian Kern said this month that Turkey was headed toward dictatorship, and that Europe should reset talks with the Turkish government.

“I do not know if the deal with Turkey will be officially terminated,” Austrian Foreign Minister Sebastian Kurz said in an interview with a German publication last week. But “what we are experiencing now are threats and the attempt by Turkey to give us an ultimatum for visa liberalization.”

On Monday, in a blunt acknowledgment of the rising tension, Turkey withdrew its ambassador from Vienna, for what Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu called “consultations.”

For months, Europe has demanded changes to Turkey’s harsh anti-terrorism legislation before it loosens its visa rules. But Turkey has fired back, pointing to the terrorist attacks that have hit the country in recent years.

Now, as Turkish authorities clamp down on dissent, the dispute is more heated than ever. Where E.U. leaders see rights violations, Turkish officials see measures necessary to head off another coup attempt.

[Turkey’s purge turns a former national hero into a fugitive]

“It cannot be that everything that is good for the E.U. is implemented by our side, but Turkey gets nothing in return,” Cavusoglu told Germany’s Bild newspaper.

“I don’t want to talk about the worst-case scenario,” he said, referring to the potential for another swell of migrants. “But it’s clear that we either apply all treaties at the same time or we put them all aside.”

Migration agencies and analysts say the consequences of the deal’s breakdown are difficult to predict. At stake is Europe’s fragile migration system, more than $6 billion in aid for refugees, and Turkey’s broader relationship with the West.

For thousands of migrants and refugees, their futures may be at risk.

Under the agreement, the E.U. can send back migrants who have arrived from Turkey in exchange for aid and visa-free travel for Turks. Before it went into effect in March, an average of 1,740 asylum seekers, mostly from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, were arriving in Greece every day, according to E.U. figures.

But by May, the average number had plummeted to just 47 a day. And aid agencies say that it was clear Turkish security forces were working to block the stream of people leaving for Greece, which is just across the Aegean Sea.

Although the number of arrivals is down, Greek authorities say they have returned only 482 of more than 10,000 people who have arrived on their shores from Turkey since March. The implementation of the agreement was slow, but deportations were delayed even further when Turkish liaison officers posted to Greece were recalled after the coup attempt, aid officials say.

As part of the wide-scale purge that has followed, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has sought to consolidate control over the security services. In addition to detaining 18,000 military personnel, Erdogan shook up command structures and placed the Turkish coast guard under the control of the Interior Ministry.

The purge “will kill the bureaucracy’s ability to think,” said Aaron Stein, an expert in Turkish politics and a resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center. “So things slow down and grind to a halt.”

[Welcome to Greece’s refugee squats]

The chaos may have also led to a rise in the number of arrivals in Greece over the past month, according to figures from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). More than 2,700 asylum seekers landed in Greece from Turkey from July 15 to Aug. 15, or about 90 a day. And although that is a fraction of last year’s influx, it’s still nearly double the late-spring average.

“We need to be prepared. Contingency, it’s important — it’s something we are doing with Greece and with other countries, telling them you need to be prepared in case this happens,” said William Spindler, a spokesman for the UNHCR.

More than 800,000 men, women and children arrived in Greece last year, overwhelming the nation’s weak response system. Any new spike in arrivals could crowd the camps Greece has established to house migrants and refugees, which are over capacity.

But the greater pressure on Europe may have abated, even if Turkey refuses to patrol its coastline for asylum seekers.

Because western Balkan nations sealed their borders this year, the migrants who make it to Greece are marooned there, unable to press northward. Germany and Sweden, once generous to new refugees, have become less so as their respective governments face domestic backlash for the influx.

“People in Turkey who had been thinking about migrating to Greece know that there they will get stuck, and Greece is not their final destination,” said Eugenio Ambrosi, the director of the E.U., Norway and Switzerland office of the International Organization for Migration, which is involved in providing aid to asylum seekers in Greece and Turkey.

“There are a series of constraints that now exist,” he said, “regardless of the deal.”

Still, a full pullback from the agreement could affect broader cooperation between Europe and Turkey — and also make life tougher for refugees.

The E.U. pledged $3.4 billion in aid for refugees in Turkey, plus up to another $3.4 billion by 2018. This funding could help ease living conditions for the 2.7 million Syrian refugees living in Turkey.

But what happens to that money if the deal falls apart is unclear. And advocacy groups have warned of the human consequences should the two sides walk away from each other.

“Canceling this agreement would inevitably risk a return to smuggling of human beings, illegal trafficking, illegal trade and a massive undermining of human rights,” said Daniel Holtgen, a spokesman for the Council of Europe, a human rights group.

But the post-coup attempt crackdown suggests to some critics that Turkey won’t be able fulfill its human rights obligations under the agreement.

“It’s another nail in the coffin of the deal,” Elizabeth Collett, director of the Brussels-based Migration Policy Institute Europe, said of the crackdown. “It’s another reason to be skeptical.”