Colin Thubron reflects on a place where empires flourish and crumble.

At the confluence of three strategic waters—the Bosporus, the Marmara, and the Golden Horn—the center of Istanbul occupies the skyline like an oriental Manhattan. Its gray-blue stone touches it with a steely glamour. The old palace of the sultans crouches on its promontory’s edge; nearby rises the cupola of Hagia Sophia, the greatest church of Orthodox Christendom; and over all ascend the pencil minarets of the city’s first mosques.

Wander these streets beyond the usual tourist trail and you are often in the labyrinth of a gently deteriorating past. Window grilles look onto imperial cemeteries; wooden mansions survive among the concrete; Byzantine walls crumble on the periphery. This, perhaps—the survival into modernity of a decaying splendor—is what imbues Istanbul with its pervasive melancholy. As Constantinople it presided over two of the longest-lasting empires in history: the Byzantine and the Ottoman. Both, in their prolonged old age, became bywords for decadence; and the feel of a long, heartsick twilight is never far away. This is the mournful hüzün of Orhan Pamuk, the country’s foremost writer: almost a quality in the air. The weather, indeed, may have something to do with it: in summer a drowsy and debilitating humidity sets in.

It was this soporific past from which Kemal Atatürk, the country’s 20th-century modernizer, removed the capital to the bracing Anatolian plateau of Ankara. Istanbul was not only the power base of his enemies. It was, in a sense, scarcely Turkish at all. For centuries the elite of the Ottoman administration (and its odalisques, too) had been ethnic Greeks, Slavs, Circassians, recruited as children from conquered peoples. Within a few generations the entire aristocracy, including the sultans, owned scarcely a drop of Turkish blood.

Fifty years ago, when I first knew the city, its population—little more than one and a half million—was an ancient, cosmopolitan mélange of Turks, Greeks, Jews, Armenians, Assyrian Christians, even Russians. But now the population has mushroomed to 17 million. Rural immigrants from Asia Minor have flooded into the city, seeking the proverbial gold that paves its streets. They find jobs where they can and sometimes erect their dwellings overnight on any patch of land. (An intact roof makes a home near-legal, and these gecekondular—“night-built dwellings”—are still one of the strange phenomena of the suburbs.)

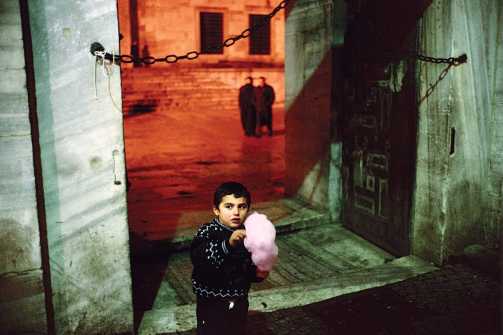

In the past half century the outflow of Greeks has escalated, their numbers dwindled now to a mere 2,000. The Armenians and Jews only nervously continue. The city’s streets and alleys bustle with a rougher, sturdier people. Satellite towns have sprung up on nearby hills; new suburbs clutter the Marmara shore, and the two bridges spanning the Bosporus bring traffic to a stupefying halt at rush hour. The change is provocative. Where is the city going? Will it absorb and temper today’s people, as it has all previous inhabitants?

Alone among cities, Istanbul bridges two continents—Europe and Asia—and this bipolar status is its pride and dilemma. If Turkey is a no man’s land between Islam and the West—its government secular, its culture Islamic—Istanbul may be its site of resolution. It may be Europe’s bridge into Islam, or Islam’s into Europe. If Turkey wants to join the European Union, Istanbul is its flagship.

At its heart the great basilica of Hagia Sophia, completed by the emperor Justinian in 537, marks the apogee of early Christian culture. In its soaring spaces—turned into a mosque by Turkish conquest in 1453, then into a museum in 1931—the tour groups dwindle to centipedes and the stupendous dome, so shallow that it seems to hang in space, drains away all sound. Beneath the semi-domes eight giant roundels proclaim the names of Allah, Mahomet and the first caliphs and heroes of Islam. They are the only obtrusive sign that this was once a mosque.

To Western sightseers, these are gaudy disruptions of the Byzantine basilica, but there are others who gaze up in wonder at the calligraphy—gold on jade green—and murmur the names inscribed there. For Istanbul, of course, is not a no man’s land at all. Despite the brutalities of past warfare, the city is home to a people whose Islam is stout but restrained, and the invocations to prayer, echoing from the loudspeakers of countless mosques, float here like familiar music.

Like The Daily Beast on Facebook and follow us on Twitter for updates all day long.

Thubron is a travel writer and novelist, whose To a Mountain in Tibet was published in April.

For inquiries, please contact The Daily Beast at [email protected].

via Colin Thubron on Istanbul – The Daily Beast.