by Adam Cole

Most folks who resolved to cut down on coffee this year are driven by the simple desire for self-improvement.

But for coffee drinkers in 17th-century Turkey, there was a much more concrete motivating force: a big guy with a sword.

Sultan Murad IV, a ruler of the Ottoman Empire, would not have been a fan of Starbucks. Under his rule, the consumption of coffee was a capital offense.

Though Murad IV banned tobacco, alcohol and coffee, some say he consumed all three and his death was the result of alcohol poisoning.

The sultan was so intent on eradicating coffee that he would disguise himself as a commoner and stalk the streets of Istanbul with a hundred-pound broadsword. Unfortunate coffee drinkers were decapitated as they sipped.

Murad IV’s successor was more lenient. The punishment for a first offense was a light cudgeling. Caught with coffee a second time, the perpetrator was sewn into a leather bag and tossed in the river.

But people still drank coffee. Even with the sultan at the front door with a sword and the executioner at the back door with a sewing kit, they still wanted their daily cup of joe. And that’s the history of coffee in a bean skin: Old habits die hard.

Wherever it spread, coffee was popular with the masses but challenged by the powerful.

“If you look at the rhetoric about drugs that we’re dealing with now — like, say, crack — it’s very similar to what was said about coffee,” Stewart Allen, author of The Devil’s Cup: Coffee, the Driving Force in History, tells The Salt.

In Murad’s Istanbul, religious leaders preached on street corners that coffee would inspire indecent behavior. As the bean moved west into Europe, physicians rallied against it, claiming that coffee would “dry up the cerebrospinal fluid” and cause paralysis.

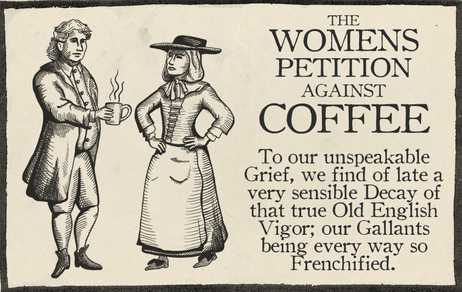

Perhaps the bawdiest argument against coffee was “The Womens [sic] Petition Against Coffee,” published in England in 1674. Brimming with innuendos that would make Shakespeare blush, the six-page manifesto blamed coffee for every type of impotence.

The male response in defense of coffee was just as heavy-handed and, predictably, even more lewd

One of the more repeatable passages:

… the Excessive use of that Newfangled, Abominable, Heathenish Liquor called COFFEE, which Riffling Nature of her Choicest Treasures, and Drying up the Radical Moisture, has so Eunucht our Husbands that they are become as unfruitful as those Desarts whence that unhappy Berry is said to be brought.

Monarchs and tyrants publicly argued that coffee was poison for the bodies and souls of their subjects, but Mark Pendergrast — author of Uncommon Grounds: The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World — says their real concern was political.

He observed that the people drinking alcohol would just get drunk and sing and be jolly, whereas the people drinking coffee remained sober and plotted against the government.

– Stewart Allen

“Coffee has a tendency to loosen people’s imaginations … and mouths,” he tells The Salt.

And inventive, chatty citizens scare dictators.

According to one story, an Ottoman Grand Vizier secretly visited a coffeehouse in Istanbul.

“He observed that the people drinking alcohol would just get drunk and sing and be jolly, whereas the people drinking coffee remained sober and plotted against the government,” says Allen.

Coffee fueled dissent — not just in the Ottoman Empire but all through the Western world. The French and American Revolutions were planned, in part, in the dark corners of coffeehouses. In Germany, a fearful Frederick the Great demanded that Germans switch from coffee to beer. He sent soldiers sniffing through the streets, searching for the slightest whiff of the illegal bean.

In England, King Charles II issued an order to shut down all coffeehouses after he traced some clever but seditious poetry to them. The backlash was throne-shaking. In just 11 days, Charles reversed his ruling.

“I think maybe he recalled that they had beheaded his father,” Pendergrast says. “He didn’t want to stir up too much trouble.”

And so coffee took its place in the center of culture. Where so many other underground movements — religious, political, even musical — were squashed, coffee managed to go mainstream.

According to legend, even the Pope Clement VIII couldn’t resist coffee’s charms. After inspecting the drink, he remarked to his skeptical advisers, “Why, this Satan’s drink is so delicious that it would be a pity to let the infidels have exclusive use of it.”

Papal advisers told Pope Clement VII that coffee was the antithesis of communion wine. He disagreed, and laid the foundation for the strictest of Catholic traditions: coffee hour

So to all you caffeine-fasters and New Year’s resolvers, I say good luck. I hope you have more discipline than the pope and more strength than the Ottoman Empire.

via Drink Coffee? Off With Your Head! : The Salt : NPR.