Turkey’s Ottoman revival

Daniel Craig may have revamped the Bond franchise but, for all the praise, Skyfall isn’t being credited with reviving interest in the British empire’s foreign policy, or in black knitted ties worn with cream shirts and dark blue suits, or even in scrambled eggs à la Bond (incessantly stirred, not shaken), a recipe Ian Fleming actually attached to the short story, 007 in New York, and which he was photographed cooking.

The production values of the ‘Ottomanalia’ industry are much higher today

– Ranier Fsadni

But something like all that is being attributed to the Turkish film, Conquest, 1453 (Fetih, 1453 in Turkish), about the Ottoman capture of Constantinople. The film came out in February and since then has fired hearts, minds and loins. The film has spawned a TV show.

There are clubs dedicated to historical enactments of glorious Ottoman victories. There is a flourishing taste for Ottoman beards, decorative motifs (walls, offices and even business cards) and dressing up as sultans and nobles.

Conquest is hardly the first feel-good Turkish film set in the glory days of empire. The popularity of such films has waxed and waned. But this epic, released in 12 countries (Middle East, Germany and the US) has become the highest-earning Turkish film ever: its cost of $18.2 million was a record but so was the $40 million grossed in Turkey and Europe. The buzz has earned it a feature in the New York Times.

Our own Maltese experience with Great Siege enactments should tell us that, no matter how earnest the ‘historical research’ is claimed to be, what emerges tends to be schlock and myth, more to do with our own fantasies than life back then. It’s the same with Conquest and its brethren.

A few years ago, the Cypriot anthropologist, Yiannis Papadakis, wrote about the experience of watching such films as part of his compelling account of discussing identity with Turks and (Turkish) Cypriots in Istanbul.

His friends and acquaintances often treated their identity with irony and amusement and, in his Echoes from the Dead Zone (2005), Papadakis himself gives a tongue-in-cheek film guide to help non-Turkish speakers distinguish the heroic Ottomans from the dastardly Byzantines.

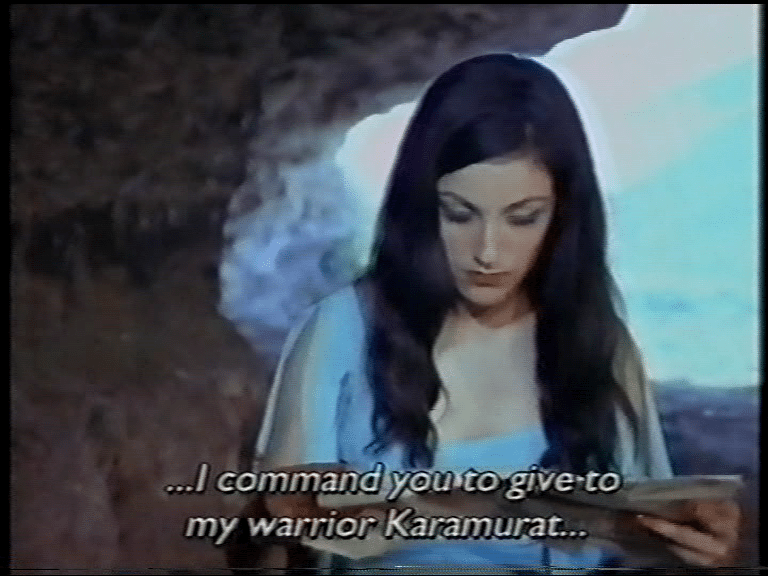

On the one hand, Turkish men are the good looking ones, with decent table manners; they win battles even when outnumbered by 20 to one (thanks to expert skill in karate, swordsmanship and American wrestling). All women – even the jaded, debauched Byzantines – fall in love with them.

On the other hand, Byzantine men are ugly and, when bald and bearded to boot, are inevitably torturers. They dribble while eating meat with their dirty hands and rape the beautiful-but-chaste Turkish women. In the end, they get what they deserve because they can’t help but stand frozen in amazement as their artful opponent leaps towards them with a number of forward somersaults before delivering the fatal blow.

The Byzantine women, meanwhile, are never chaste and their parts were played (at least in the late 1980s) by soft-porn actresses.

No great surprise, then, to learn that Conquest presents the court of Constantine XI, the last Byzantine emperor, as pullulating with nubile dancing girls and punch-drunk hedonists.

Papadakis hastens to add that when he was living in Turkey two decades ago almost no one watched such films. The only people who watched did so to laugh and catch the director’s mistakes (the watch on the hero’s wrist, the telephone lines behind the rushing chariot…). So why the popularity in 2012?

The production values of the ‘Ottomanalia’ industry are much higher today. Still, the industry has many critics in Turkey itself, people who frown at the jingoism. The critics of the critics, in their turn, say that too much is being read into what is essentially entertainment. They can also point to last year’s $70 million earnings from Turkey’s soap opera exports.

Being low-brow entertainment, however, does not make it insignificant. Popular entertainment is often the theatre where culture idly plays with new possibilities.

In this case, renewed popularity is no doubt partly a matter of fashion. But not only. The last 10 years of the Islamist Erdogan government have seen Turkey recover strongly from the economic bust of 2002. A new, affluent middle class is culturally comfortable with Erdogan’s brand of Islamist nationalism and consumerism; it is ready to re-interpret the Ottoman past in the light of its own experience.

And that experience includes the country’s re-assertion on the regional stage. While the Syrian crisis is a potential threat to Turkey’s own unity (given the impact of Syria’s increasingly unbound Kurds on Turkey’s minority), the turbulence of the region also highlights Turkey’s prosperity and relative stability, while Europe grows pale beside it.

Turkey doesn’t welcome the wedge that the crisis is driving between its interests and Russia’s, yet, the fact that Turkey is ready to criticise Russia’s role on the UN Security Council does highlight its growing confidence. Any wonder why the latest Ottoman craze is accompanied by a popular amateur interest in ancient foreign policy?

We may yet look back at Conquest as the watershed that, for all its kitsch, stood for the indefinable moment when the debate on EU membership in Turkey began to swing decisively against membership.

via Turkey’s Ottoman revival – timesofmalta.com.