Southeast Turkey is home to one of the oldest Christian civilizations in the world – the Assyrians who were among the first to convert to Christianity. Among their ancient traditions is making wine, in a way that has changed little since the time of the Roman Empire. But the region they live in is at the center of a bloody conflict between Kurdish rebels and the Turkish state, and most fled the region to Europe and the U.S. But in the town of Midyat in southeast Turkey a few people are keeping the winemaking tradition alive.

Tradition

Assyrian Christian Yusuk Uluisik is crushing grapes by hand – a ritual that has not changed for centuries.

“From our fathers and grandfathers, all the way back to the time of the Jesus, we are making wine in the same way. My family has been making wine here and drinking it for centuries,” he explained. “Every year they produce two to three small barrels and put them indoors until they are ready. Then we drink two to three glasses with oily food.”

Gradually the juice of the grapes pours out of the bottom of a stone pot and trickles down a stone trench where it is collected and then stored in large plastic containers to ferment.

Once he was one of hundreds of families making wine but now he is just one of a few left. Most departed to escape fighting between Kurdish rebels and the Turkish state during the 1980’s and 90’s.

“In the past there was little demand, he noted. “Maybe a few bottles at Christmas, to a few Christian families that were left. As everyone else had gone abroad to escape the fighting and for a better life. But in the last five years there has been some kind of revival. There are many tourists visiting and we can’t produce enough to meet the demand.”

More tourists

The growing number of tourists visiting this ancient part of Turkey is a testament to the return of peace and growing prosperity.

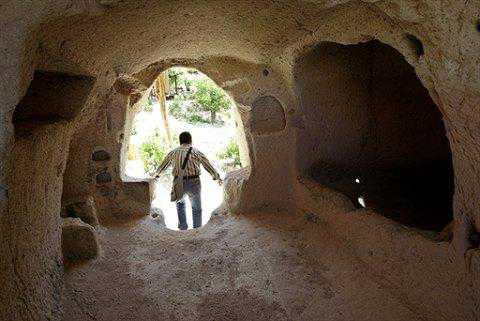

“Assyrians used to live here. They used to make their prayers everything. As you can see the windows look to east,” said Kaya Gulersan, the manager of a boutique hotel. “In the belief of Assyrians, the day of reincarnation, Jesus Christ rises from the east. And that’s why in a cemetery of the Assyrians they, have been buried sitting down not lying, therefore waiting for the day to come to greet Jesus.”

The luxurious hotel opened a year ago. It is has been renovated into a grand Assyrian-style building, a reminder of past prosperity of Assyrian Christians which once made more up than 80 percent of the town’s population.

Drinking a glass of locally-produced wine with Gulersan he explains the opportunity to discover one of Christianity’s oldest communities is drawing people from around world and providing a small boom for wine makers like Yusuf.

“They come here to see the churches,” he explained. “There is one here called Mor Gabria which is 1,600 years old. A few weeks ago I had 60 orthodox Greeks who feasted her. Next week some Italians. We have visitors from all nations. About two weeks we had a family, [the father] he left 25 to 26 years ago. He brought his family. He showed his children where he was born. They are returning more and more and there is a village here. Assyrian origin Swiss citizens, they are are building their own town here.”

The town Gulersan is referring to is Kafkoy, about 40 kilometers away from Midyat .

Back to motherland

Kafkoy is a hive of activity. Abandoned in the 1990’s by its inhabitants at the height of the conflict between the state and the PKK, it still shows the scars of that conflict. But five years ago, a few Assyrian families returned from Switzerland to bring the town back to life.

Yakup Demir was one of the first to come back.

“It was always in our mind to return back. We are people of this land. We are the oldest people of this land,” he said. “We have been here almost 5,000 years. This is our land our motherland we belong here he said. But, he says, the situation here didn’t allow us to stay here or even visit. But the world is changing, Turkey is changing and even people around here are changing so we decided to return.

Warm memories

Walking around newly built houses of the growing community Demir explains memories of wine making remain strong along with plans to bring back the tradition.

He says you can see, all around are grape vines, they are all overgrown now, but this region is famous for the quality of grapes. He said he can remember as a child here making wine, the whole village would come together to make wine every year. He says we even made spirits with the grape seeds. But now we are planning to build a proper vineyard.

As we walk through the village, we come across two Assyrian Christian visitors from Europe. They are arguing about whether it is the right time to move back.

Although the region here is at peace, fears remain of a return to a full scale conflict between the Kurdish rebels and the Turkish state as peace efforts falter. But, Demir says he is an optimist, proudly pointing to their rebuilt village, as his vindication, adding that he hopes in the near future this region will be famous more for its wine than conflict.

via VOA | Ancient Winemaking Makes Resurgence in Southeast Turkey | News | English.