Curator: Fulya Erdemci

Organised by Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts

Design by Ruben Pater, LAVA Amsterdam.

The notion of the public domain as a political forum will be the focal point of the 13th Istanbul Biennial. This highly contested concept will serve as a matrix to generate ideas and develop practices that question contemporary forms of democracy, challenge current models of spatio-economic politics, problematise the given concepts of civilisation and barbarity as standardised positions and languages, and above all, unfold the role of contemporary art as an agent that both makes and unmakes what is considered public.

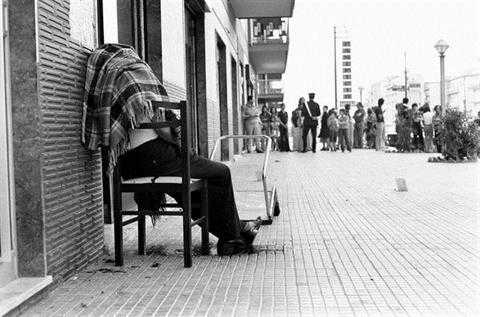

Fragility: Am I not a citizen?

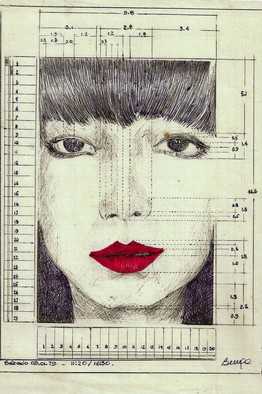

The title of the Istanbul Biennial “Mom, am I barbarian?” is a quote from the Turkish poet Lale Müldür’s book of the same title.

As a critique of the highest form of civilisation and rationality, which has produced a world of barbarity in its negative sense, many artists of the Western tradition have advocated historically what was primordial, primitive and irrational (Romanticism, Primitivism, Fauve, Dada and Surrealism, for example). This is also true of today. In the face of excessive production, connectivity and complexity in the world, the simple and direct (and their opposites, the over-complicated and convoluted) are espoused as an expression of the desire to start anew. Against the alarming incompetence of cities, governances and regimes, there is an increase in retreat to start anew, develop new communities (new collective living experiments) and alternative economic systems.

The term “barbarian” originates from the ancient Greek word “barbaros,” which referred to non-Greek people and meant “foreigner/stranger”; those who cannot speak the language properly. In the Middle Ages, it also denoted non-Christians, and later on, non-Westerners. Certainly, the etymological origin and historical and contemporary meanings of the word are loaded with strong connotations of exclusion. Strikingly in this context, in ancient Greek, barbarian was the antonym of “politis,” the “citizen,” coming from the polis, the Greek city-state. It is a term that relates inversely to the city and the rights of those within it. What does it mean to be a good citizen today, in Istanbul, for example? In the midst of ongoing urban transformations—the “battleground”—does it mean to conform to the existing status quo or take part in the acts of civil disobedience? Neo-liberal urban policies advocate the implementation of free market parameters that lead to socio-economic Darwinism, which in turn creates a wilderness, where the powerful beat the weak. Can’t we imagine another social contract in which citizens assume responsibility for each other, even for the weakest ones, those most excluded?

In the current context, what does it mean to be a barbarian? After all, galvanising the limits of the civilised, the “barbarian” reflects the “absolute other” in society, circumnavigating the frames of identity politics and multicultural discourses. But, what does the reintroduction of barbarity as a concept reveal today? Is it a response to an urge to go beyond already existing formulas, towards the unknown? It may refer to a state of fragility, with potential for radical change (and/or destruction), thus, to the responsibility to take new positions. Through the unique interventions of artists, the biennial exhibition aims to explore further such pressing questions and will ask if art can foster the construction of new subjectivities to rethink the possibility of “publicness” today.

Public Alchemy: Public programme

An integral part of the exhibition, the public programme will bring artistic production and knowledge production together in the months prior to and throughout the exhibition. Artists, architects, planners, theoreticians, activists, poets and musicians will come together to examine the ways in which publicness can be reclaimed as an artistic and political tool in the context of global financial imperialism and local social fracture.

The Public Programme is co-curated by Dr Andrea Phillips, who is currently a Reader in Fine Art in the Department of Art and Director of the Doctoral Research Programmes in Fine Art and Curating, Goldsmiths, University of London.

NB: 12th Biennale de Lyon from 12 September to 29 December, 2013

Preview: 10–11 September, 2013 / www.biennaledelyon.com

Istanbul Biennial

Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts

Nejat Eczacıbaşı Binası

Sadi Konuralp Caddesi No:5

Şişhane 34433 İstanbul Turkey

T +90 212 334 07 64

F +90 212 334 07 05

13b.iksv.org

Media Relations

Elif Obdan

T + 90 212 334 07 13

Accreditations

13b.iksv.org/tr/akreditasyon

13b.iksv.org/en/accreditation

via Mom, am I barbarian? | e-flux.