CQ Transcripts Wire

Tuesday, April 7, 2009; 8:57 AM

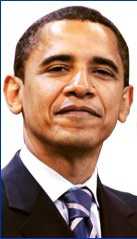

PRESIDENT OBAMA: Thank you so much. Well, it is a great pleasure to be here. Let me begin by thanking Professor Rahmi Aksungur — did I say that properly — who is director of the university here. And I want to thank all the young people who’ve gathered together. This is a great privilege for me and I’m really looking forward to it. I’m going to make a few remarks at the beginning and then I want to spend most of the time having an exchange and giving you an opportunity to ask — ask questions of me and I may ask some questions of you.

So as I said yesterday, I came to Turkey on my first trip overseas as President for a reason, and it’s not just to see the beautiful sights here in Istanbul. I came here to reaffirm the importance of Turkey and the importance of the partnership between our two countries. I came here out of my respect to Turkey’s democracy and culture and my belief that Turkey plays a critically important role in the region and in the world. And I came to Turkey because I’m deeply committed to rebuilding a relationship between the United States and the people of the Muslim world — one that’s grounded in mutual interest and mutual respect.

Turkey and the United States have a long history of partnership and cooperation. Exchanges between our two peoples go back over 150 years. We’ve been NATO allies for more than five decades. We have deep ties in trade and education, in science and research. And America is proud to have many men and women of Turkish origin who have made our country a more dynamic and a more successful place. So Turkish- American relations rest on a strong foundation.

That said, I know there have been some difficulties in recent years. In some ways, that foundation has been weakening. We’ve had some specific differences over policy, but we’ve also at times lost the sense that both of our countries are in this together — that we have shared interests and shared values and that we can have a partnership that serves our common hopes and common dreams.

So I came here to renew that foundation and to build on it. I enjoyed visiting your parliament. I’ve had productive discussions with your President and your Prime Minister. But I also always like to take some time to talk to people directly, especially young people. So in the next few minutes I want to focus on three areas in which I think we can make some progress: advancing dialogue between our two countries, but also advancing dialogue between the United States and the Muslim world; extending opportunity in education and in social welfare; and then also reaching out to young people as our best hope for peaceful, prosperous futures in both Turkey and in the United States.

Now, let me just talk briefly about those three points.

First, I believe we can have a dialogue that’s open, honest, vibrant, and grounded in respect. And I want you to know that I’m personally committed to a new chapter of American engagement. We can’t afford to talk past one another, to focus only on our differences, or to let the walls of mistrust go up around us.

Instead we have to listen carefully to each other. We have to focus on places where we can find common ground and respect each other’s views, even when we disagree. And if we do so I believe we can bridge some of our differences and divisions that we’ve had in the past. A part of that process involves giving you a better sense of America. I know that the stereotypes of the United States are out there, and I know that many of them are informed not by direct exchange or dialogue, but by television shows and movies and misinformation. Sometimes it suggests that America has become selfish and crass, or that we don’t care about the world beyond us. And I’m here to tell you that that’s not the country that I know and it’s not the country that I love.

America, like every other nation, has made mistakes and has its flaws. But for more than two centuries we have strived at great cost and sacrifice to form a more perfect union, to seek with other nations a more hopeful world. We remain committed to a greater good, and we have citizens in countless countries who are serving in wonderful capacities as doctors and as agricultural specialists, people — teachers — people who are committed to making the world a better place.

We’re also a country of different backgrounds and races and religions that have come together around a set of shared ideals. And we are still a place where anybody has a chance to make it if they try. If that wasn’t true, then somebody named Barack Hussein Obama would not be elected President of the United States of America. That’s the America I want you to know.

Second, I believe that we can forge a partnership with Turkey and across the Muslim world on behalf of greater opportunity. This trip began for me in London at the G-20, and one of the issues we discussed there was how to help peoples and countries who, through no fault of their own, are being very hard hit by the current world economic crisis. We took some important steps to extend a hand to emerging markets and developing countries by setting aside over a trillion dollars to the International Monetary Fund and by making historic investments in food security.

But there’s also a larger issue of how Turkey and America can help those who have been left behind in this new global economy. All of our countries have poverty within it. All of it — all of our countries have young people who aren’t obtaining the opportunities that they need to get the education that they need. And that’s not just true here in Turkey or in the United States, but that’s true around the world. And so we should be working together to figure out how we can help people live out their dreams.

Here there’s great potential for the United States to work with Muslims around the world on behalf of a more prosperous future. And I want to pursue a new partnership on behalf of basic priorities: What can we do to help more children get a good education? What can we do to expand health care to regions that are on the margins of global society? What steps can we take in terms of trade and investment to create new jobs and industries and ultimately advance prosperity for all of us? To me, these are the true tests of whether we are leaving a world that is better and more hopeful than the one we found.

Finally, I want to say how much I’m counting on young people to help shape a more peaceful and prosperous future. Already, this generation, your generation, has come of age in a world that’s been marked by change that’s both dramatic and difficult. While you are empowered through unprecedented access to information and invention, you’re also confronted with big challenges — a global economy in transition, climate change, extremism, old conflicts but new weapons. These are all issues that you have to deal with as young people both in Turkey and around the world.

In America, I’m proud to see a new spirit of activism and responsibility take root. I’ve seen it in the young Americans who are choosing to teach in our schools or volunteer abroad. I saw it in my own presidential campaign where young people provided the energy and the idealism that made effort possible. And I’ve seen it wherever I travel abroad and speak to groups like this. Everywhere I go I find young people who are passionate, engaged, and deeply informed about the world around them.

So as President, I’d like to find new ways to connect young Americans to young people all around the world, by supporting opportunities to learn new languages, and serve and study, welcoming students from other countries to our shores. That’s always been a critical part of how America engages the world. That’s how my father, who was from Kenya, from Africa, came to the United States and eventually met my mother. It’s how Robert College was founded so long ago here in Istanbul.

Simple exchanges can break down walls between us, for when people come together and speak to one another and share a common experience, then their common humanity is revealed. We are reminded that we’re joined together by our pursuit of a life that’s productive and purposeful, and when that happens mistrust begins to fade and our smaller differences no longer overshadow the things that we share. And that’s where progress begins.

So to all of you, I want you to know that the world will be what you make of it. You can choose to build new bridges instead of building new walls. You can choose to put aside longstanding divisions in pursuit of lasting peace. You can choose to advance a prosperity that is shared by all people and not just the wealthy few. And I want you to know that in these endeavors, you will find a partner and a supporter and a friend in the United States of America.

So I very much appreciate all of you joining me here today. And now what I’d like to do is take some questions. I think we’ve got — do we have some microphones in the audience? So what I’d like to do is people can just raise their hands and I’ll choose each person — if you could stand up and introduce yourself. I have a little microphone in my pocket here in case you’re speaking Turkish, because my Turkish is not so good — (laughter) — and I’ll have a translator for me.

OK? All right. And I want to make sure that we end before the call to prayer, so we have about — it looks like we have about half an hour. All right? OK, we’ll start right here.

QUESTION: I’m from the university. I want to ask some questions about climate issue. Yesterday you said that peace in home and peace in world, but to my opinion, firstly the peace should be in nature. For this reason, I wonder that when the USA will sign the Kyoto Protocol.

OBAMA: Well, it’s an excellent question. Is this mike working? It is? OK. Thank you very much. What was your name?

QUESTION: (Inaudible.)

OBAMA: As many of you know, I think the science tells us that the planet is getting warmer because of carbon gases that are being sent into the atmosphere. And if we do not take steps soon to deal with it, then you could see an increase of three, four, five degrees, which would have a devastating effect — the oceans would rise; we don’t know what would happen to the beauty of Istanbul if suddenly the seas rise. Changing weather patterns would create extraordinary drought in some regions, floods in others. It could have a devastating effect on human civilization. So we’ve got to take steps to deal with this.

When the Kyoto Protocol was put forward, the United States opted out of it, as did China and some other countries — and I think that was a mistake, particularly because the United States and — is the biggest carbon — has been the biggest carbon producer. China is now becoming the biggest carbon producer because its population is so large. And so we need to bring an international agreement together very soon.

It doesn’t make sense for the United States to sign Kyoto because Kyoto is about to end. So instead what my administration is doing is preparing for the next round, which is — there will be discussions in Copenhagen at the end of this year. And what we want to do is to prepare an agenda both in the United States and work internationally so that we can start making progress on these issues.

Now, there are a number of elements. Number one, we have to be more energy efficient. And so all countries around the world should be sharing technology and information about how we can reduce the usage of electricity, and how we can make our transportation more efficient, make our cars get better gas mileage. Reducing the amount of energy we use is absolutely critical.

We should also think about are there ways that if we’re using fossil fuels — oil, coal, other fossil fuels — are there ways of capturing or reducing the carbon emissions that come from them?

So this is going to be a big, big project and a very difficult one and a very costly one. And I don’t want to — I don’t want to lie to you: I think the politics of this in every country is going to be difficult, because if you suddenly say to people, you have to change your factory to make it more energy efficient — well, that costs the factory owner money. If you say to a power plant, you have to produce energy in a different way, and that costs them money, then they want to pass that cost on to consumers, which means everybody’s electricity prices go up — and that is something that is not very popular.

So there are going to be big political struggles in every country to try to ratify an agreement on these issues. And that’s why it’s going to be so important that young people like yourself who will be suffering the consequences if we don’t do something, that you are active politically in making sure that politicians in every country are responsive to these issues and that we educate the public more than we have so far.

But it is excellent question, thank you.

All right, this gentleman right here.

QUESTION: Thank you. I’m studying at Bahcesehir University, and my major is energy engineering, so…

OBAMA: Oh, there you go. You could have given an even better answer.

QUESTION: Yes, I hope we will solve that problem in the future. So my question is, what actions will you take after you wrote quote, peace at home, peace at the world, to do…

OBAMA: I’m sorry, could you repeat the question?

QUESTION: What actions will you take after you wrote your quote, peace at home and peace at the world, to — (inaudible) — and what do you think, as Turkish young men and women, how can we help you at this purpose you have?

OBAMA: Well, some people say that maybe I’m being too idealistic. I made a speech in Prague about reducing and ultimately eliminating nuclear weapons, and some people said, ah, that will never happen. And some people have said, why are you discussing the Middle East when it’s not going to be possible for the Israelis and the Palestinians to come together? Or, why are you reaching out to the Iranians, because the U.S. and Iran can never agree on anything?

My attitude is, is that all these things are hard. I mean, I’m not naive. If it was easy, it would have already been done. Somebody else would have done it. But if we don’t try, if we don’t reach high, then we won’t make any progress. And I think that there’s a lot of progress that can be made.

And as I said in my opening remarks, I think the most important thing to start with is dialogue. When you have a chance to meet people from other cultures and other countries, and you listen to them and you find out that, even though you may speak a different language or you may have a different religious faith, it turns out that you care about your family, you have your same hopes about being able to have a career that is useful to the society, you hope that you can raise a family of your own, and that your children will be healthy and have a good education — that all those things that human beings all around the world share are more important than the things that are different.

And so that is a very important place to start. And that’s where young people can be very helpful, because I think old people, we get into habits and we become suspicious and we carry grudges. Right? You know, it was interesting when I met with President Medvedev of Russia and we actually had a very good dialogue, and we were — we spoke about the fact that although both of us were born during the Cold War, we came of age after the Cold War had already begun to decline, which means we have a slightly different attitude than somebody who was seeing Russia only as the Soviet Union — only as an enemy or who saw America only as an enemy.

So young people, they can get rid of some of the old baggage and the old suspicions, and I think that’s very important. But understanding alone is not enough. Then you — we actually have to do the work.

And for the United States, I think that means that we have to make sure that our actions are responsible, so on international issues like climate change we have to take leadership. If we’re producing a lot of pollution that’s causing global warming, then we have to step forward and say, here’s what we’re willing to do, and then ask countries like China to join us.

If we want to say to Iran, don’t develop nuclear weapons because if you develop them then everybody in the region is going to want them and you’ll have a nuclear arms race in the Middle East and that will be dangerous for everybody — if we want to say that to Iranians, it helps if we are also saying, “and we will reduce our own,” so that we have more moral authority in those claims.

If we want to communicate to countries that we sincerely care about the well-being of their people, then we have to make sure that our aid programs and our assistance programs are meaningful.

So words are good and understanding is good, but ultimately it has to translate into concrete actions. And it takes time. I was just talking to my press team and they were amused because some of my reporter friends from the States were asking, how come you didn’t solve everything on this trip? They said, well, you know, it’s only been a week. These things take time and the idea is that you lay the groundwork and slowly, over time, if you make small efforts, they can add up into big efforts. And that’s, I think, the approach that we want to take in promoting more peace and prosperity around the world.

OK, let me make sure I get all sides of the room here. This young lady right here.

QUESTION: In one of your interviews you said you want us to be a member of the European Union. But after that, Nicolas Sarkozy said, it’s not yours, it’s European Union decision. Now I want to ask you that what’s your opinion, and why Nicolas Sarkozy said that? Is that because he’s more likely to support the so-called Armenian genocide?

OBAMA: You know, the — I don’t think — well, first of all, it’s true, I’m not a member of — the United States is not a member of the European Union, so it’s not our decision to make. But that doesn’t prevent me from having an opinion. I mean, I notice the Europeans have had a lot of opinions about U.S. policy for a long time, right? They haven’t been shy about giving us suggestions about what we should be doing, so I don’t think there’s anything wrong with us reciprocating. That’s what friends do — we try to be honest about what we think is the right approach. I think it is the right approach to have Turkey join the European Union. I think if Turkey can be a member of NATO and send its troops to help protect and support its allies, and its young men are put in harm’s way, well, I don’t know why you should also not be able to sell apricots to Europe, or have more freedom in terms of travel.

So I think it’s the right thing to do. I also think it would send a strong signal that Europe is not monolithic but is diverse and that that is a source of strength instead of weakness. So that’s my opinion.

Now, President Sarkozy is a good friend and a good ally. As I said, friends are going to sometimes disagree on this. I haven’t had a lengthy conversation with him about his position on this issue. My hope is, is that as time goes on and as trust builds, that this is ultimately something that occurs.

I don’t get a sense that his opposition is related to the Armenian issue. I don’t think that’s it. I think it’s a more fundamental issue of whether he’s confident about Turkey’s ability to integrate fully. But you’ll probably have to ask him directly. So maybe when he comes here he’ll have a town hall meeting like this one.

OK, the gentleman right there. Yes, go ahead. Here’s a microphone.

QUESTION: First, I will ask about the Bush and you differences at the core, because some say just the face has changed and that — but core is the same still. They will have a fight with the Middle East and they will have a fight with Iran.

And my second question is more in part to this. You will let the Kurdish state in northern Iraq? You will let — you’ll allow this?

OBAMA: OK, the…

QUESTION: Thank you.

OBAMA: Yes. Well, let me answer — I’ll answer the Kurdish question first. You know, we are very clear about our position on Turkish territorial integrity. Turkey is an ally of ours and part of what NATO allies do is to protect the territorial integrity of their allies. And so we are — we would be opposed to anything that would start cutting off parts of Turkey, and we have been very supportive in efforts to reduce terrorist activity by the PKK.

Now, I also think that it’s important that the Kurdish minority inside of Turkey is free to advance in the society and that they have equal opportunity, that they have free political expression, that they are not suppressed in terms of opportunity. And I think that the President and Prime Minister are committed to that, but I want to continually encourage allowing — whether it’s religious minorities or ethnic minorities — to be full parts of the society. And that, I think, is very, very important.

The first question, if I understood you correctly, is the suggestion that even though I present a different face from Bush, that the policies are the same and so there’s really not much difference.

And, you know, I think this will be tested in time because as I said before, moving the ship of state is a slow process. States are like big tankers, they’re not like speedboats. You can’t just whip them around and go in a new direction. Instead you’ve got to slowly move it and then eventually you end up in a very different place.

So let me just give you a few examples. When it comes to Iraq, I opposed the war in Iraq. I thought it was a bad idea. Now that we’re there, I have a responsibility to make sure that as we bring troops out, that we do so in a careful enough way that we don’t see a complete collapse into violence. So some people might say, wait, I thought you were opposed to the war, why don’t you just get them all out right away? Well, just because I was opposed at the outset it doesn’t mean that I don’t have now responsibilities to make sure that we do things in a responsible fashion.

When it comes to climate change, George Bush didn’t believe in climate change. I do believe in climate change, I think it’s important. That doesn’t mean that suddenly the day I’m elected I can say, OK, we’re going to turn off all the lights and everybody is going to stop driving. Right? All I can do is to start moving policies that over time are going to obtain different results.

And then it is true, though, that there are some areas where I agree with many of my friends in the United States who are on the opposite political party. For example, I agree that Al Qaida is an enormous threat not just to the United States but to the world. I have no sympathy and I have no patience for people who would go around blowing up innocent people for a political cause. I don’t believe in that.

So, yes, I think that it is just and right for the United States and NATO allies and other allies from around the world to do what we can to eliminate the threat of Al Qaida. Now, I think it’s important that we don’t just do that militarily. I think it’s important that we provide educational opportunities for young people in Pakistan and Afghanistan so that they see a different path. And so my policies will be somewhat different, but I don’t make any apologies for continuing the effort to prevent bombs going off or planes going into buildings that would kill innocents. I don’t think any society can justify that.

And so, as I said, four years from now or eight years from now, you can look back and you can see maybe what he did wasn’t that different, and hopefully you’ll come to the conclusion that what I did made progress.

Yes, this young lady right here.

QUESTION: First of all, welcome to our country, Turkey. I would like to continue in Turkish if it’s possible.

OBAMA: Yes, let me — wait, wait, wait. See, I’ve got my…

QUESTION: Thank you very much.

OBAMA: Hold on.

QUESTION: (As translated.) My first question is that in the event that Turkey becomes an EU member, what — how will that — how is that…

OBAMA: OK, try again.

QUESTION: In the event that Turkey becomes a member of the EU, how will that affect U.S. foreign policy and the alliance of civilizations? And my second question is a little more personal. We watched your election with my American friends. Before you were elected, my friends who said that they were ashamed of being Americans, after you were elected said that they were proud to be Americans. This is a very sudden and big change. What do you think the reason is for this change?

OBAMA: You know, the United States friendship with Turkey doesn’t depend on their EU membership. So even if Turkey continued not to be a member of the EU, the United States in our bilateral relations and in our relations as a NATO ally can really strengthen progress. And I had long discussions with the President and the Prime Minister about a range of areas where we can improve relations, including business and commerce and trade.

We probably can increase trade between our two countries significantly, but we haven’t really focused on it. Traditionally the focus in Turkish-American relations has been around the military and I think for us to broaden that relationship and those exchanges could be very important.

You know, in terms of my election, I think that what people felt good about was it affirmed the sense that America is still a land of opportunity. I was not born into wealth. I wasn’t born into fame. I come from a racial minority. My name is very unusual for the United States. And so I think people saw my election as proof, as testimony, that although we are imperfect, our society has continued to improve; that racial discrimination has been reduced; that educational opportunity for all people is something that is still available. And I also think that people were encouraged that somebody like me who has a background of living overseas, who has Muslims in his family — you know, that I might be able to help to build bridges with other parts of the world.

You know, the American people are a very hopeful people. We’re an optimistic people by nature. We believe that anything is possible if we put our minds to it. And that is one of the qualities of America that I think the world appreciates. You know, sometimes people may think that we are — we aren’t realistic enough about how the world works and we think that we can just remake the world without regard to history, because we’re still a relatively new nation. Compared to Turkey and how old this civilization is, America is still very new.

And so it’s true that I think we believe that things can happen very fast and that transformations in politics or in economics or in science and technology can make our lives better overnight. So sometimes we need more patience. But I also think the world needs to have a sense — (drop in audio feed). That’s a good thing and that we don’t have to always be stuck with old arguments. I mean, one thing that is interesting about Europe as I travel around is, you know, you hear disputes between countries that date back to a hundred years, a thousand years — people are still made about things that happened a very long time ago.

And so one thing America may have to offer is an insistence on looking forward and not always looking backwards.

OK, I only have time for one more question. I’ll give it to this gentleman right here.

Oh, wait, wait, wait, wait — I’ve got to get my earplug.

QUESTION: I thank you for the opportunity to ask you a question. Right now I am in the Turkish language and literature faculty of this university. How do you assess the Prime Minister’s attitude in Davos? Had you been in the same situation, would you have reacted the same way?

OBAMA: Well, first of all, I think very highly of your Prime Minister. I’ve had a chance now to talk with him first in London. I had spoken to him on the phone previously, but we had the opportunity to meet in London during the G-20, and then we’ve been obviously having a number of visits while I’ve been here in Turkey.

And so I think that he is a good man who is very interested in promoting peace in the region and takes great pride I believe in trying to help work through the issues between Israel and its neighbors. And Turkey has a long history of being an ally and a friend of both Israel and its neighbors. And so it can occupy a unique position in trying to resolve some of these differences.

I wasn’t at Davos so I don’t want to offer an opinion about how he responded and what prompted his reaction. I will say this — that I believe that peace in the Middle East is possible. I think it will be based on two states, side by side: a Palestinian state and a Jewish state. I think in order to achieve that, both sides are going to have to make compromises.

I think we have a sense of what those compromises should be and will be. Now what we need is political will and courage on the part of leadership. And it is not the United States’ role or Turkey’s role to tell people what they have to do, but we can be good friends in encouraging them to move the dialogue forward.

I have to believe that the mothers of Palestinians and the mothers of Israelis hope the same thing for their children. They want them not to be vulnerable to violence. They don’t want, when their child gets on a bus, to worry that that bus might explode. They don’t want their child to have to suffer indignities because of who they are. And so sometimes I think that if you just put the mothers in charge for a while, that things would get resolved. And it’s that spirit of thinking about the future and not the past that I just talked about earlier that I think could help advance the peace process, because if you look at the situation there, over time I don’t believe it’s sustainable.

It’s not sustainable for Israel’s security because as populations grow around them, if there is more and more antagonism towards Israel, over time that will make Israel less secure.

It’s not sustainable for the Palestinians because increasingly their economies are unable to produce the jobs and the goods and the income for people’s basic quality of life.

So we know that path is a dead end, and we’ve got to move in a new direction. But it’s going to be hard. A lot of mistrust has been built up, a lot of anger, a lot of hatred. And unwinding that hatred requires patience. But it has been done. You know, think about — my Special Envoy to the Middle East is a gentleman named George Mitchell, who was a senator in the United States and then became the Special Envoy for the United States in Northern Ireland. And the Protestants and the Catholics in Northern Ireland had been fighting for hundreds of years, and as recently as 20 years ago or 30 years ago, the antagonism, the hatred, was a fierce as any sectarian battle in the world.

And yet because of persistent, courageous efforts by leaders, a peace accord was arrived at. A government that uses the democratic process was formed. And I had at the White House just a few weeks ago the leader of the Protestants, the leaders of Catholics in the same room, the separatists and the unionists in the same room, as part of a single system. And so that tells me that anything is possible if we’re willing to strive for it.

But it will depend on young people like you being open to new ideas and new possibilities. And it will require young people like you never to stereotype or assume the worst about other people.

In the Muslim world, this notion that somehow everything is the fault of the Israelis lacks balance — because there’s two sides to every question. That doesn’t mean that sometimes one side has done something wrong and should not be condemned. But it does mean there’s always two sides to an issue.

I say the same thing to my Jewish friends, which is you have to see the perspective of the Palestinians. Learning to stand in somebody else’s shoes to see through their eyes, that’s how peace begins. And it’s up to you to make that happen.

All right. Thank you very much, everybody. I enjoyed it. (Applause.)

END

2 p.m. local time after concluding an eight-day overseas tour through Europe.

2 p.m. local time after concluding an eight-day overseas tour through Europe.