Iran has always presented a thorn in the eye of Western policy makers since the Pahlavi dynasty and its resurgent nationalism. Being strategically located in a position that affords it to patrol and play a significant part in monitoring and controlling the flux of forty percent of the world’s oil flows, the foreign policies of superpower governments teetered between soliciting Iranian support and stability through backing and the focused undermining of Iranian regional power. Throughout modern history, we have seen both policy aims carried out with effect. The crux of the issue is Iran’s power to blockade the Strait of Hormuz and its military capability to do so. Looming over this immediate outcome is Iran’s power as a multiethnic nation state with vast oil, mineral, and gas resources. Its large coastline with the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea also affords it power that it is able to project within the spheres of the Gulf States, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. One of the aims of Iran’s nuclear program is to solidify its hold on regional power and prevent any foreign intrigue from upsetting this influence.

Iran has always presented a thorn in the eye of Western policy makers since the Pahlavi dynasty and its resurgent nationalism. Being strategically located in a position that affords it to patrol and play a significant part in monitoring and controlling the flux of forty percent of the world’s oil flows, the foreign policies of superpower governments teetered between soliciting Iranian support and stability through backing and the focused undermining of Iranian regional power. Throughout modern history, we have seen both policy aims carried out with effect. The crux of the issue is Iran’s power to blockade the Strait of Hormuz and its military capability to do so. Looming over this immediate outcome is Iran’s power as a multiethnic nation state with vast oil, mineral, and gas resources. Its large coastline with the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea also affords it power that it is able to project within the spheres of the Gulf States, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. One of the aims of Iran’s nuclear program is to solidify its hold on regional power and prevent any foreign intrigue from upsetting this influence.

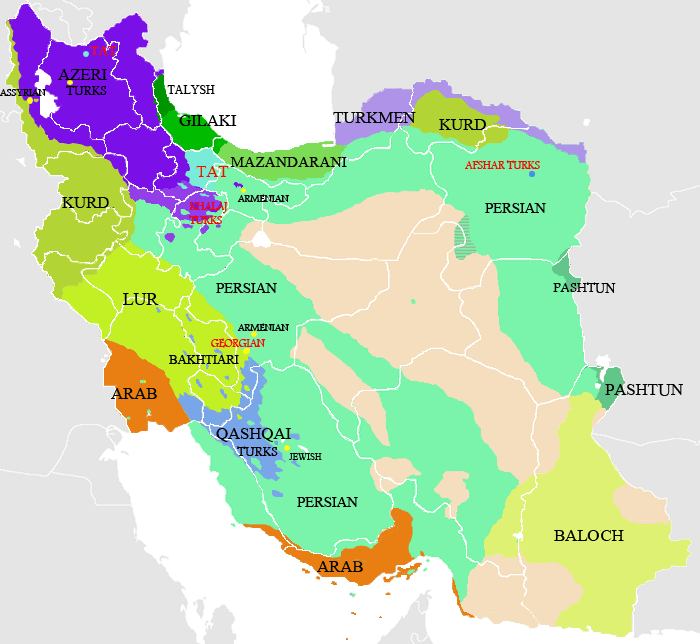

This is why the response to Iran’s nuclear program won’t just be surgical strikes. In the short term, a surgical strike or any other military action aimed at destabilizing Iran and setting back its atomic aims will do exactly that, but it will not curb Iran’s two main resources- human capital in the form of knowledge and raw material wealth. This is where separatism comes into play. The majority of Iran’s oil and gas resources are located in the Khuzestan and Hormozgan provinces, home to many ethnic Arabs. Another large chunk of oil and gas is located near and within the Caspian Sea; areas inhabited by ethnic Azeris. Any policy of providing a mortal blow to Iran will factor in ethnic tensions and the creation of new nation-states from the mammoth corpse of what used to be known as Iran. The establishment of a Kurdish Republic of Mahabad was one of the efforts put into separatism, and while unsuccessful, it demonstrated that with enough foreign funding and support, an independent republic carved out of one of Iran’s minority-held provinces is feasible and beneficial for multiple parties. A resourceless Iran poses no threat to Arab states, the increasing regional power of Azerbaijan, nor the struggling states of Pakistan and Afghanistan. And without such resources, Iran doesn’t stand a chance at mobilizing its human capital in nation-strengthening efforts that could potentially pose a threat.

The policy does, however, pose some risks. For one, a Kurdistan carved out of Iran will destabilize and effectively plunge Turkey into ethnic war. Already, an autonomous Kurdish republic is in effect in the state of Iraq, and has also gone into effect in Syria. The next steps are Iran and Turkey- Iran being the weaker and more unstable holder of Kurd-inhabited territories. A war with Iran will provide the instability and resource sapping necessary for the formation of an autonomous Kurdistan in western Iran. The trouble starts when the Kurds of Turkey begin to demand their own autonomy. Perhaps it is a worthwhile deal for Turkish inclusion into Europe, and for the promotion of stability in a region haunted by war and sectarianism. What remains to be seen is whether the Kurds, given autonomy in Iraq, Syria, Iran, and Turkey, will opt to secede and form a resource-rich nation-state. However, it seems the Kurdistan dilemma is an inevitability; preventing 45 million people from forming a nation-state is an uphill battle for all parties involved.

Any formation of an Arab state from Southwestern Iran would serve the goal of limiting Iran’s coastline in the Gulf and resource wealth. It would be eagerly supported by Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Kingdoms, and with enough repression from Iran, will evoke international support. This will effectively cripple Iran as a nation and plunge it into Afghanistan-grade poverty within several generations. The question of Azerbaijan remains. While separatists and pan-Turkists declare that Iranian Azeris suffer discrimination, facts on the ground hold otherwise. Azeris serve high positions in Iranian society and politics, and enjoy lifestyles similar to ethnic Persians. Furthermore, the historical link of the land of Azerbaijan (northern and southern) is part and parcel of Iranian history. The Land of Fire was the hub of Zoroastrianism and Persian culture for eons. It is unclear whether separatism will take hold as a popular sentiment in Iranian Azerbaijan. It is greatly dependent on how well the Republic of Azerbaijan in the north does in the coming years, as it fosters greater relations with the United States and Europe. If standard of living and economic mobility in the country rise simultaneously as quality of life, political and social repression, and economic rot plague Iran, the desire to join their brothers in the north will increase.

And why would international players be apprehensive about this option in the long run? The momentary instability that will rise from carving new states out of Iranian territory is a tradeoff that pales in comparison the the benefits of stronger trading partners in the area, the goodwill of neighboring countries, and the loss of the threat to oil flow in the Gulf and the Caucasus. An Iran without Kurdistan, Azerbaijan, and Khuzestan will be an immobile and poverty-stricken land. The secession of barren Baluchistan will also rob Iran of its rich mineral resources. The goal is to ensure Iran will never pose a threat to international interests in the Middle East- without the resources and strategic advantages it holds, it will never be able to pose such a threat again. Minority groups may be apprehensive- they may hold the belief that they have greater opportunities as Iranians in socioeconomic mobility, yet a concerted support and funding effort from the international community can dissolve such apprehension at the prospect of separation.

Iran is “The Land of the Aryans” much as Yugoslavia was the land of the Slavs. It does not have a consistent national identity that rests on three pillars- language, ethnicity, and religion. Thus far, religion is the tie that binds many Iranians, and to an extent, language. This is why Iran is adamant on excluding Azeri and Kurdish as national tongues, as such moves may dissolve Iranian national unity. A state without a national identity resting on the aforementioned pillars provides a tempting opportunity for more powerful players to play the ethnic tension card. In this sense, whatever Iranian government in power must learn to adeptly play at identity politics and mitigate the forces of separatism and ethnic division. Thus far, all of Iran’s governments have done poorly in mitigating these differences, often resulting in crises and near-losses for the nation state of Iran. As Iran’s tension with the international community grows, a dismembered Land of the Aryans continues to become a very real possibility in our lifetime.

Source: iranian.com