Airport Exchange 2010 in Istanbul brought together a broad church of industry luminaries to address the more pressing issues of the air transport sector. From regulatory issues and Single European Sky to modernisation and charging models, the event was billed as “a series of individually tailored conferences addressing the critical issues affecting the air transport sector”.

Organised by ACI Europe and ACI Asia, Airport Exchange 2010, was held in Istanbul from 04 to 06-Oct-2010 and attended by some 1000 delegates, covered 20 topics over five conferences.

Five of the topics for review were: Regulatory Issues; SES/SESAR and Airports; How to Address Current Obstacles to Airport Development, Modernisation and Expansion; Market Regulation; and Airport Charges: Innovative Charging Models.

The opening address of the Airport Operations conference was delivered by President ofACI Europe and Chief Operating Office for the Schiphol Group, Ad Rutten. He addressed extensively Apr-2010’s volcanic ash cloud in Europe and presented a diary of events that catalogued the day-by-day development of the crisis. Up to 80% of airspace was closed, 100,000 flights cancelled and 9.5 million passengers could not travel. EUR250 million in revenue was lost by European airports, which did not benefit from the EUR450 million fuel cost savings made by airlines, to offset their EUR1.3 billion operating loss.

“National governments have little interest in aviation”

Mr Rutten argued there were three clear lessons from the crisis:

- National governments appear to have little interest in supporting aviation;

- Implementing the Single European Sky is an immediate and urgent priority;

- Aviation is essential to the life of Europe’s citizens and businesses.

He suggested an eight-point follow-up plan to be implemented by the EU including: the establishment of a steering task force of three commissioners; regular meetings of transport ministers; a crisis coordination cell; and acceleration of SES II. He put four questions for further discussion:

- Who should be responsible for taking care of stranded passengers, airports or airlines?

- Who will take the costs, such as parking charges, for stranded aircraft?

- Which entities are primarily responsible in terms of decision making?

- Should airports have a greater coordination role and what opportunities, but also burdens, could this role bring to airports?

The first working session of the Airport Operations conference covered the subject of regulation.

Dr Holger Schultz – CEO of Airsight, a consultant to air traffic service organisations – reviewed the EASA study on the implementation of provisions contained in ICAO Annex 14 on Aerodromes in the EASA member states. His damning summary was that the legal framework and transposition is very heterogeneous and partly inconsistent; that authorities are understaffed; that certification requirements vary from “nothing” to “highly sophisticated”; that there is a wide range of variations at almost all aerodromes; and that awareness of the handling of deviations is limited at some aerodromes with a significant difference in handling between member states.

Let’s go for business class

Corporate Legal Counsel Aviation at the Schiphol Group and Vice-Chair of ACI Europe’s Single European Sky Steering Group, Ilona Crommentuijn, concluded the session by asking whether European airports are taking an “economy class” or “business class” approach to what she described as “the Single European Sky aircraft”. Pointing to the existing regulatory framework, the “pillar” of airport capacity and ATM airport performance she concluded that European airports have already “boarded” the Single European Sky aircraft, and that ACI Europe’s SES Steering Group is taking care of the interests of the European airports. She ended with the plea, “Let’s go for business class!”

Thorsten Astheimer of Fraport’s Air Traffic Solutions Division spoke on the same issue in the third working session on SES/SESAR and Airports. He argued today’s situation in European air traffic could be summed up as follows:

- European airspace is already close to saturation in some regions and society’s demand for mobility is growing;

- Despite the growing demand many large hub airports are already operating close to their capacity limit;

- The highly fragmented airspace over Europe is resulting in limited capacity, delays and high costs for airlines and passengers;

- The legal framework may be highly different from state to state (and airport to airport);

- Only a system-wide approach can overcome the blocking issues in Europe.

How to Address Current Obstacles to Airport Development, Modernisation and Expansion

The session “How to Address Current Obstacles to Airport Development, Modernisation and Expansion” was the first in the Airport Development and Environment conference and contained contributions from Thomas Brehmer, Director Air Traffic Management for Germany’s Hochtief Airport and Hochtief AirPort Capital; Feride Gokalp, General Manager of Turkey’s TAV Construction; and Curtis Grad, CEO ofAirport International Group (AIG), the operator, manager and developer of Jordan’sQueen Alia International Airport.

5% of 2% = not a big emission contribution from airports

Mr Brehmer, who focused on developing airports’ sustainably, stated that growth in aviation should be moderated by the costs of mitigation of environmental impact and that transparency is required to initiate market mechanisms. Airports are contributing to an (environmental) solution but it is a joint problem that can only be engaged in cooperation. He reiterated that aviation’s emissions are around 622 million tons of CO2 annually, about 2-3% of the man-made total, and that the contribution of airports is just 5% of that.

He stressed that in the newly industrialised and emerging economies, growth will be almost double of developed countries’ GDP in the coming years and that, consequently, it is airport operators within these economies that will come under the microscope.

Mr Gokalp’s presentation focussed on the extension and modernisation of Ataturk Airport in the host city of Istanbul. New investments in 2010 add up to EUR30 million out of a total investment to date of EUR197 million under the PPP model, enabling the airport to handle 27.5 million passengers. However, no clue was offered as to TAV’s position on the need for a third Istanbul airport. Turkey’s Prime Minister went on to announce subsequently (30-Oct-2010) that another airport could be constructed in Istanbul “in the near future”, one of many such announcements that often amount to little.

Curtis Grad also spoke about new development at the Queen Alia airport, where USD750 million is being invested in a 100,000sqm state-of-the-art terminal due for completion in 1Q2012. He detailed three major challenges facing AIG: the limited flexibility for innovation or commercial optimisation; the requirement to build atop a live and dynamic airport site; and capacity constraints coupled with rapid traffic growth. The airport is experimenting with new concepts and operators during the construction period and with retail agreements it is moving away from flat, area-based rents, to a concession format with minimum guarantee and percentage of gross revenues.

Market Regulation: Delivering Regulation that Truly Reflects the Market

The session on Market Regulation: Delivering Regulation that Truly Reflects the Market was the third working session of the conference on Economic and Market Regulation, and featured presentations from Carmine Bassetti, head of Airports for India’sGMR; Tim Hardy, BAA Director for Airside; and Carlos Madeira, Vice President of ANA Aeroportos de Portugal.

Mr Bassetti posed the question: “Can the airport business, in the scope of a single till model, be considered sustainable/attractive in the future?” In the course of a comprehensive presentation he concluded that it depends on the price paid for the airport asset. The closer to RAB (regulatory asset base) value the more secure the investment is and easier for the regulator to incentivise the investor/operator to do better.

If, instead, the price paid for the airport asset is in the high range (a lot more than RAB), then the investment becomes risky and the investor will have to place hope in the regulator to better remunerate the investment.

For an investor, he maintained, the dual till and no till approaches are certainly more incentivising because they allow market-related returns on commercial non-aeronautical investments.

Uncertain certainty

Tim Hardy dealt with airport slots and asked: “Is there a need to review the EU Slot Regulation in light of new market developments?” His answer, which might have been the title of an album by the rock band Oasis was, “Yes … maybe”. He went on to explain that there are concerns about the current regime, but there may be a case for a “do nothing” option if amendments being considered would make the system worse, therefore “do nothing” remains a fall-back option.

Other important features of his presentation were:

- The slot coordinator should be constitutionally independent of airline, airport andANSP interests;

- Slot misuse is a major problem and new measures to address this would be strongly supported (by BAA);

- The acquisition of slots by general and business aviation (GA/BA) is not supported (by BAA). Business aviation/GA are at their most effective making use of under-used infrastructure, not occupying space in congested airports;

- Ownership/acquisition of slots by non-airlines is not supported;

- Are they slots or a “right to operate”?

- Secondary trading is not to be restricted as it encourages market fluidity.

Competition in a EUR34 billion market

Carlos Madeira concerned himself with the topic of ground handling and the revision of the Council Directive 96/67/EC, asking: “What should be the priorities?”

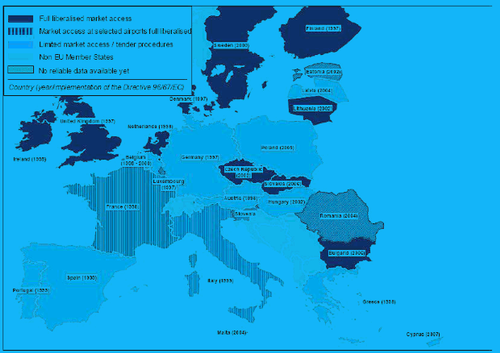

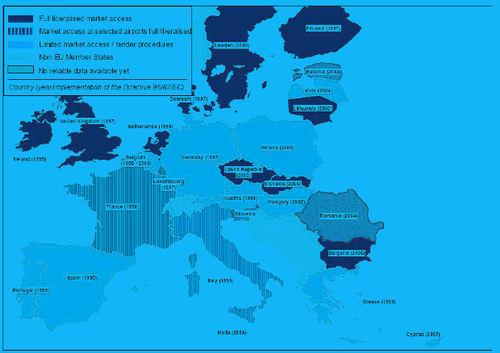

In a highly valuable technical presentation (see chart 1 below for an example) he described the evolution of the European airport ground handling industry in some detail, stating that it will continue to grow, driven by “air traffic evolution” and that the business is becoming more complex in order to satisfy different clients’ requirements. The global ground handling market is now estimated to be worth EUR34 billion, from EUR26 billion in 2003. The market share of independent ground handlers (as opposed to airlines and airports) has risen from 25% to 45% in that period.

Chart 1: Overview on types of liberalisation already achieved

Source: Presentation, Carlos Madeira

But a reduced number of large international players is trying to reshape the industry. Just eight of these players, led by Swissport – which is being sold by Ferrovial – control 15% of the industry.

For many players, the ground handling activities are less profitable than other business areas.

He concluded by saying that ANA sees no compelling reason to revise Council Directive 96/67/EC, which is proposed in order to (gradually) increase competition in the handling market and to clarify and simplify a number of provisions.

However, in case such a revision takes place, some points could and should be clarified and/or improved. For example, ANA believes an additional effort should be made to ensure that the existing directive is fully implemented in all member states. Also, passenger airports shouldn’t be subjected to market experiments in the ground handling industry “just because it’s nice to make a few changes from time to time”.

Airport Charges: Innovative Charging Models

Airport Charges: Innovative Charging Models was the fourth and final session of theEconomic and Market Regulation conference, and featured presentations from Nazareno Ventola, Planning and Control Director of Bologna Airport in Italy; Dr Richard Sharp, Director of Jacobs Consultancy; and Alberto Baldi, Planning and Control Manager of SEAAeroporti di Milano.

Fun for airlines

Nazareno Ventola – after pointing out the traffic growth at Bologna in 2010, with more than a little help from Ryanair – dealt with the “myth” and “reality” at Italian airports. The myths include claims that airports with an average EBITDA of 30-40% are the “rich and fat” part of the air transport market chain and that airport charges are too high and costs out of control. The realities are that a high operating margin is essential to finance necessary infrastructure development and that, in Italy, airport charges have been frozen since 2001 and have therefore decreased in real terms.

The new Italian economic regulation agreement’s reference rule is the ‘Delibera Cipe 38/2007, which was approved in 2008 and which is aimed at the pre-financing of urgent infrastructure investments for those airport managing bodies that expressly request it. But as the result of a complex process, with multiple subjects involved at different stages, only a small number of agreements (eg Pisa, Naples and Apulia airports) have been put in place. The basic principles of the new system include: price cap on regulated services; charges must be consistent with actual costs (operating, depreciation, capital); incentives linked to quality and environmental performance; and the introduction of a “hybrid till” system.

Mr Ventola described the whole charging procedure as it works now as “fun – for the airlines” and concluded that the world is changing and that the new paradigm is “deregulate!”.

Airport-driven hub

Milan’s Alberto Baldi focused on charging strategies for an airport catering to legacy and low-cost carriers and spent some time on the new competitive scenario of the “airport-driven hub” or new generation hub, where the airport operator encourages the establishment of competitive connections between network carriers and LCCs and provides ad hoc infrastructures and organisational devices to facilitate those connections.

He also pointed to airport alliances as an effective competitive response to the evolution of the sector as some international examples show, such as AdP-Schiphol and the East Asia Airport Alliance.

He added that SEA is working on the creation of a North of Italy airport system that aims at taking new market opportunities by the integration of different airports.

He concluded by stating that charging systems depend on regulatory models and that current regulation is based on the principle that “airport = monopoly”. There are many ways of integrating legacy carriers and LCCs such as new generation hub models and airport alliances. The boom of LCCs is deeply changing the air transport market (certainly true of Italy) and airports should re-think their traditional business model. Legacy and low-cost carriers can coexist at the same airport in an integrated model.

Finally, Richard Sharp touched on a similar theme: “How can a single defined pricing strategy for an airport accommodate charges for low cost carriers?” Referring to the “big stick”, the EU’s Airport Charges Directive, he opined that no policy needs to be entirely cost based or follow a single method or rule, but that it should be “systematic‟; not discriminate; follow what an airport actually does rather than an idealised model that the airport cannot live up to; and be capable of being supported by evidence if required.

Six times the utilisation of a scarce resource

Mr Sharp pointed to an example from Bristol Airport, UK. A typical regional airline is achieving three turnarounds per day with 80 seats and a 60% load factor, thus carrying 288 passengers, while an LCC has six daily turnarounds with 85% load factor on 160 seats, thus carrying 1928 passengers, which he describes as “over six times the utilisation of a scarce resource”.

Answering the question, “What makes a justifiable charge?”, he stated that the key criteria are:

- That it has credible economic justification;

- That it best promotes airport development, the long-term interests of passengers and the wider public interest.

For example, it reflects:

- Viability of airport;

- Competitive position;

- Opportunity to develop greater number and greater range of services;

- Efficiency of use;

- Promotion of cost effective capital expenditure.

Also, can they survive the scrutiny of airlines and the regulator and be implemented?

He concluded:

- A charges policy supports the overall strategy for developing the airport and provides a means for defending the airport’s position;

- There are a number of features of low-cost traffic which suggest that charges should be lower;

- Costs are one consideration for setting charges but not necessarily the only fair approach;

- There are a range of potential tools for an airport to use in support of reasonable commercial objectives;

- The ideal solution may not help you if you are not able to implement it;

- ”Everyone gets some of what they want – no one gets all of what they want‟.

Following the foundation of the State of Israel in 1948, a Cuban airline and a group of Cuban pilots were commissioned to transport all the Jewish people who wished to immigrate to the dawning state. Their many flights between 1951 and 1952 as part of what may be the largest air evacuation in human history had remained unknown until now.

Following the foundation of the State of Israel in 1948, a Cuban airline and a group of Cuban pilots were commissioned to transport all the Jewish people who wished to immigrate to the dawning state. Their many flights between 1951 and 1952 as part of what may be the largest air evacuation in human history had remained unknown until now.