ANTHONY SHADID and DAVID D KIRKPATRICK

ANALYSIS : Puritanical Islamists are vying with more liberal ones to impose their vision of the world on the Middle East

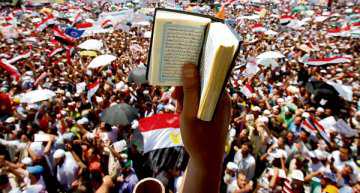

BY FORCE of this year’s Arab revolts and revolutions, activists marching under the banner of Islam are on the verge of a reckoning decades in the making: the prospect of achieving decisive power across the region has unleashed an unprecedented debate over the character of the emerging political orders they are helping to build.

BY FORCE of this year’s Arab revolts and revolutions, activists marching under the banner of Islam are on the verge of a reckoning decades in the making: the prospect of achieving decisive power across the region has unleashed an unprecedented debate over the character of the emerging political orders they are helping to build.

Few question the coming electoral success of religious activists, but as they emerge from the shadows of a long, sometimes bloody, struggle with authoritarian and ostensibly secular governments, they are confronting newly urgent questions about how to apply Islamic precepts to more open societies.

In Turkey and Tunisia, culturally conservative parties founded on Islamic principles are rejecting the name “Islamist” to stake out what they see as a more democratic and tolerant vision.

In Egypt, a similar impulse has begun to fracture the Muslim Brotherhood as a growing number of politicians and parties argue for a model inspired by Turkey, where a party with roots in political Islam has thrived in a once-adamantly secular system. Some contend that the absolute monarchy of puritanical Saudi Arabia in fact violates Islamic law.

A backlash has ensued, as well, as traditionalists have flirted with time-worn Islamist ideas like imposing interest-free banking and obligatory religious taxes and censoring irreligious discourse.

The debates are deep enough that many in the region believe the most important struggles may no longer be between Islamists and secularists, but rather between the Islamists themselves, pitting the more puritanical against the more liberal.

“That’s the struggle of the future,” said Azzam Tamimi, a scholar and the author of a biography of a Tunisian Islamist, Rachid Ghannouchi, whose party, Ennahda, is expected to dominate elections next month to choose an assembly to draft a constitution.

The moment is as dramatic as any in recent decades in the Arab world, as autocracies crumble and suddenly vibrant parties begin building a new order, starting with elections in Tunisia in October, then Egypt in November. Though the region has witnessed examples of ventures by Islamists into politics, elections in Egypt and Tunisia, attempts in Libya to build a state from scratch and the shaping of an alternative to Syria’s dictatorship are their most forceful entry yet into the region’s still embryonic body politic.

“It is a turning point,” said Emad Shahin, a scholar on Islamic law and politics at the University of Notre Dame who was in Cairo.

At the centre of the debates is a new breed of politician who has risen from an Islamist milieu but accepts an essentially secular state, a current that some scholars have already taken to identifying as “post-Islamist”. Its foremost exemplars are prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party in Turkey, whose intellectuals speak of a shared experience and a common heritage with some of the younger members of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and with the Ennahda party in Tunisia. Like Turkey, Tunisia faced decades of a state-enforced secularism that never completely reconciled itself with a conservative population.

“They feel at home with each other,” said Cengiz Candar, an Arabic-speaking Turkish columnist. “It’s similar terms of reference, and they can easily communicate with them.”

Ghannouchi has suggested a common ambition, proposing what some say Erdogan’s party has managed to achieve: a prosperous, democratic Muslim state, led by a party that is deeply religious but operates within a system that is supposed to protect liberties.

“If the Islamic spectrum goes from bin Laden to Erdogan, which of them is Islam?” Ghannouchi asked in a recent debate with a secular critic. “Why are we put in the same place as a model that is far from our thought, like the Taliban or the Saudi model, while there are other successful Islamic models that are close to us, like the Turkish, the Malaysian and the Indonesian models, models that combine Islam and modernity?”

In Libya, Ali Sallabi, the most important Islamist political leader, cites Ghannouchi as a major influence. Abdel Moneim Abou el-Fotouh, a former Muslim Brotherhood leader running for president in Egypt, has joined several breakaway political parties in arguing that the state should avoid interpreting or enforcing Islamic law, regulating religious taxes or barring a person from running for president based on gender or religion.

A party formed by three leaders of the Brotherhood’s youth wing says that while Egypt shares a common Arab and Islamic culture with the region, its emerging political system should ensure protections of individual freedoms as robust as the West’s. One of them, Islam Lotfy, argues that the strictly religious kingdom of Saudi Arabia, where the Koran is ostensibly the constitution, was less Islamist than Turkey. “It is not Islamist; it is dictatorship,” said Lotfy, who was recently expelled from the Brotherhood for starting the new party.

Egypt’s Centre Party, a group that struggled for 16 years to win a licence from the ousted government, may go furthest here in elaborating the notion of post-Islamism. Its founder, Abul-Ela Madi, has long sought to mediate between religious and liberal forces, even coming up with a set of shared principles last month. Like the Ennahda party in Tunisia, he disavows the term “Islamist” and, like other progressive Islamic activists, he describes his group as Egypt’s closest equivalent to Erdogan’s “neither secular nor Islamist. We’re in between.”

It is often said in Turkey that its political system, until recently dominated by the military, moderated Islamic currents there. Lotfy says he hopes that Egyptian Islamists will undergo a similar, election-driven evolution. But, compared with Turkey, the stakes of the debates may be even higher in the Arab world, where divided and weak liberal currents pale before the organisation and popularity of Islamic activists.

In Syria, debates rage among activists over whether a civil or Islamic state should follow the dictatorship of Bashar al-Assad, if he falls. The emergence in Egypt, Tunisia and Syria of Salafists, the most inflexible currents in political Islam, is one of the most striking political developments. (“The Koran is our constitution,” goes one of their sayings.)

And the most powerful current in Egypt, still represented by the Muslim Brotherhood, has stubbornly resisted some of the changes in discourse. When Erdogan expressed hope for “a secular state in Egypt”, meaning, he explained, a state equidistant from all faiths, Brotherhood leaders immediately lashed out, saying that Erdogan’s Turkey offered no model for either Egypt or its Islamists.

A Brotherhood spokesman, Mahmoud Ghozlan, accused Turkey of violating Islamic law by failing to criminalise adultery. “In the secularist system, this is accepted, and the laws protect the adulterer,” he said, “But in the Shariah law this is a crime.”

As recently as 2007, a prototype Brotherhood platform sought to bar women or Christians from serving as Egypt’s president and called for a panel of religious scholars to advise on the compliance of any legislation with Islamic law. The group has never disavowed the document. Its rhetoric of Islam’s long tolerance of minorities often sounds condescending to Egypt’s Christian minority, which wants to be afforded equal citizenship, not special protections.

Indeed, Tamimi, the scholar, argued that some mainstream groups like the Brotherhood were feeling the tug of their increasingly assertive conservative constituencies, which still relentlessly call for censorship and interest-free banking.

“Is democracy the voice of the majority?” asks Mohammed Nadi, a 26-year-old student at a recent Salafist protest in Cairo. “We as Islamists are the majority. Why do they want to impose on us the views of the minorities – the liberals and the secularists? That’s all I want to know.” – ( New York Times )