By M K Bhadrakumar

The Arab Spring has apparently had no impact whatsoever on Europe’s entrenched views on Turkey. This much becomes clear from the annual report of the European Commission (EC) on Turkey issued in Brussels on Wednesday. The report took stock of Turkey’s reform program in terms of its membership bid of the European Union (EU) and roundly censured the country over human rights and its increasingly acrimonious spat with Cyprus.

Conceivably, the EC report mummifies for a long time Turkey’s EU bid, which has spluttered in the past year or two. To add insult to injury, the EC gave the green light to two of Ottoman Turkey’s “grandchildren” in the Balkans – Serbia and Montenegro – on their respective aspirations to join the European club.

Recent months have been a heady period for Turkey, which has convinced itself that the new Middle East taking shape in the upheaval of the Arab Spring would find it irresistible as a role model, and that the Western world would inevitably be compelled to revise its opinions and view Turkey in an altogether new light as the torchbearer of enlightenment in the Muslim world.

Wednesday’s EC report comes as a reality check. The more things seemed to change, the more they remain the same. The EC report chastised Turkey about the lack of freedom of expression, women’s rights and freedom of religion as falling below accepted standards in the liberal democracies of Europe. It estimated that the shortfalls continued to disqualify Turkey from joining the EU.

In a scathing reference, the EC report said, “In Turkey, the legal framework does not yet sufficiently safeguard freedom of expression. The high number of legal cases and investigations against journalists and undue pressure on the media raise serious concern.”

Worn-out lens

The harsh criticism by the EC comes as an embarrassment when the leadership of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been riding the wave of the Arab Spring in the Muslim Middle East and exhorting the Arab world to follow Turkey’s unique example of combining or reconciling – depending on one’s point of view – Western-style liberal democracy with Islam.

During his recent visit to Cairo, an assertive Erdogan crossed the Rubicon of Islam and gave audacious advice to the Egyptian people about the virtues of secularism – at a juncture when the Muslim Brotherhood is surging in that country and could be at the threshold of entering the corridors of power.

Curiously, the EC report has been received with ennui in Turkey. As prominent editor Murat Yetkin put it, “The truth is that fewer and fewer people in Turkey care about what the EU is saying on the country day by day.” Yet, Turkey’s Minister for Europe, Egemen Bagis, responded polemically to the EC report and alleged that the human-rights record of many EU member countries couldn’t be “half as good as Turkey’s”.

He said the EC report was simply out of focus:

Although the report tries to take an objective and balanced picture of Turkey, we think that the camera used by the commission is old with a worn-out lens and the lens needs to be changed, as the picture has taken lots of blurred parts and the camera seems to be zooming on the false points.

Bagis maintained for the record that Turkey would not be detracted from its chosen path of an EC-membership bid. However, he added the caveat that “full membership is Turkey’s only goal, no other goals can be accepted”. Turkey bristles at the “privileged partnership” that has been mooted by France and Germany as an alternative to regular membership.

Objectively, the EC report is fair and balanced. It commends the Erdogan government for initiating civilian supremacy over the military, is supportive of his agenda to draw up a new constitution and even praises Turkey’s economic policies. On the other hand, it flags Turkey’s poor record of individual liberty and civil rights, the rule of law, freedom of expression, women’s rights and the erosion of the autonomy of regulatory bodies. “Significant further efforts are required to guarantee fundamental rights in most areas.”

However, these European perspectives don’t surprise Turkey. The common perception in Turkey is that Brussels keeps coming up with excuses for not admitting Turkey into what is essentially a Christian club. The EC decision to encourage the membership bid by Serbia and Montenegro and to leave Turkey’s accession hanging will only reinforce the grouse of “cultural” discrimination toward Turks.

The latest EC report may also have shifted the goal posts by introducing a new template, namely, Turkey’s latest acrimonious rift with Cyprus, which erupted over gas deposits in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The report criticized Turkey for its strong reaction to the recent gas drilling by Cyprus in the Eastern Mediterranean and for carrying the rift to a potential flashpoint by starting its own seismic exploration in the region under a Turkish naval presence. It demanded that Turkey should make progress in normalizing relations with Cyprus and avoid “any kind of threat, source of friction or action that could damage good neighborly relations and the peaceful settlement of disputes”.

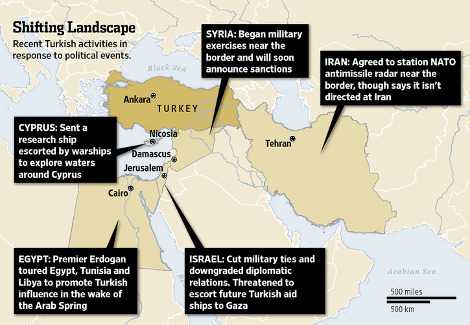

Evidently, the new assertiveness in Turkey’s regional policies is not going down well in European opinion. In addition to Turkey’s showdown with Cyprus, European countries have been urging Ankara to address the tensions in its relations with Israel, but Erdogan has been in no mood to listen, and the rupture with Israel happens to be the one issue that has probably overnight made him a hero on the Arab street, while it has cost Turkey virtually nothing.

Europe always took with a pinch of salt Turkey’s claims to play a leadership role in its surrounding regions. It sidelined Turkey’s swagger in the Balkans in the project over the disbandment of Yugoslavia; more recently, France initially didn’t even invite Turkey to the conclave discussing the Western intervention in Libya, although Arab countries were invited.

Tunisia surges

Most certainly, Europe (especially France) will ignore Turkey’s claim for any leadership role in Syria or the Levant, leave alone in the Maghreb region. The vocal supporter of Turkey’s regional leadership of a democratic Middle East happens to be Saudi Arabia and it has a special interest in doing so. French President Nicolas Sarkozy went to the Caucasus recently and put down Turkey rather harshly in an unwarranted display of derision.

The paradox, as the EC report implies, is that Turkey’s own exciting reform program has ground to a virtual halt in the recent past, while Erdogan has been exhorting the Middle East to reform. Thoughtful Turkish commentators realize this contradiction. One of Turkey’s most respected political observers, Sedat Ergin, drew attention to this in a column this week titled “The problem of fine-tuning policies on Syria”.

Ergin wrote, “As soon as the winds named ‘Arab Spring’ started blowing, [Turkey] took the stance supporting the demands for change and democracy.” Turkey’s choice, he argued, was and is essentially correct, but a contradiction nonetheless arises when Turkey expresses such robust opinions favoring democratic reform. Ergin pointed out:

The Syrian regime’s actions against the opposition groups coincide with a time when Peace and Democracy Party [Kurdish political party] members are being subjected to mass arrests, when elected deputies are kept in jails and when the space for the Kurdish political movement to operate within democratic bounds is being entirely constricted in Turkey.

Credit must be given to Erdogan that such frank discussions on the Kurdish problem are possible at all in today’s Turkey, whereas, before his advent to power, the Kurdish problem itself used to be forbidden terrain for public discourse. All the same, the past two years have been more or less barren, and Erdogan was even regressive on the democratization front despite being so advantageously placed in Turkish domestic politics.

Erdogan needs to pay heed to the EC report when it gently underscores that Turkey is neglecting to do its own homework while immersed in espousing the cause of democratization in the Middle East. Out of the 35 chapters of the EU’s Acquis Communautaire that Turkey is expected to comply with to gain membership, negotiations have begun on only 13 chapters in the entire period since 2005 when the accession talks began under Erdogan’s stewardship.

The EU, it increasingly appears, was actually the driving force behind Erdogan’s democratization program, and today the disconcerting reality is that Turkey may be losing interest in the EU membership project. A leading Turkish columnist, Semih Idiz, summed up the mood:

Turkish-EU membership talks are currently at a standstill, with little prospect of being revived soon … EU is not something the majority of Turks look to with confidence or enthusiasm anymore … The average Turk is aware of the obstacles strewn on Turkey’s path … Put another way, the “EU stick” simply does not work anymore … because the “EU carrot” is not enticing for Turkey anymore, especially at a time of turmoil in Europe itself.

Indeed, Turkey’s resounding success as an economic power-house during Erdogan’s rule and the crisis shaking the European economies do present contrasting pictures that are misleading public opinion that Turkey could as well do without EU membership. No doubt, the EU’s political leverage on Turkey is diminishing.

If so, where will a fresh impetus for reform come from? The Turkish official claim is that the government has an innate urge to reform the country, no matter the EU membership bid. But that isn’t a convincing enough argument. So, could it be from the Arab Spring, which, ironically, Erdogan is charioting abroad?

As Tunisia heads for an historic poll on October 23 to elect an assembly that would frame a new constitution, Islamist leader Rachid Ghannouchi stole a march over Erdogan by fielding as candidate for the Ennahda party in the capital, Tunis, a woman who does not wear a head scarf. Even after nearly nine decades of constitutional rule, Turkey has not reached a comparable point.

Ambassador M K Bhadrakumar was a career diplomat in the Indian Foreign Service. His assignments included the Soviet Union, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Germany, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Kuwait and Turkey.