28 July 2013

The Honorable Barack H. Obama

President of the United States

The White House

1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW

Washington, DC 20500

USA

Dear Mr. President:

It has been three years since I last wrote to you advising that there was a political force rising in Turkey to throw off the Islamo-Fascist ruling party, the now infamous AKP. Mr. President, you know AKP well, even embracing the malevolent prime minister as a friend. I am sorry for the harm this has done to your reputation and America’s. This damage is irreducible and nothing can be done either for you or the Turkish prime

minister. But plenty can and should be done for the Turkish people.

I was wrong in using the words “political force” in my earlier letter. The force that has arisen transcends politics and politicians. It is sui generis and it is for real. Its name, GEZI PARK RESISTANCE; its success is inevitable. Inevitable, yes, inevitable despite you and your agents destructive and subversive meddling with the democratic, secular Republic of Turkey. The world knows the truth, Mr. President, that the AKP is the main

destructive force in Turkey. And before the Turkish Constitutional Court was destroyed it opined similarly.

After a ten-year on-going coup by the now-radical Islamic AKP, Turkey is fully under occupation. You and your CIA and all your other subversive operators have achieved another great victory over another secular country. For shame, Mr. President, to spout about democratic values the while undermining and destroying all institutions along with the culture essential for democracy. There is no democracy in Turkey. And that’s why the Turkish youth took to the streets. To restore the nation’s embrace of the founding principles of Atatürk. To assure that they, the Turkish young people, would have a viable future, just like young people in America. You wouldn’t gas them, would you, Mr. President? Then why, in the middle of all this unspeakable violence, did you sell the lamentable Erdoğan even more toxic pepper gas? Why? (I have copies of the invoices, Mr. President.)

To maim the young, patriotic Turkish democrats who chose to fight for their freedom? Over ten thousand injured. Eleven have lost eyes from gas capsules directly aimed at their faces by the fascist police. 106 people suffered severe head trauma damage. Five dead. And blindings, poisonings, deaths, beatings by the police, and pursuits by AKP “civilian” police with scimitars… And now eleven thousand more imprisoned in an AKP nazi-style round-up. And still you sell this criminal government more deadly chemicals for the desperate Erdoğan to injure, blind and kill his fellow Turkish citizens. History will not be kind to you for this, Mr. President. Nor will it be kind to your mouse of an ambassador, one Francis Ricciardone, who described the AKP government’s apalling violence against Atatürk’s Turkish Youth as its having a “conversation about your future.” Such a conversation! Such disgusting words! What benumbed diplomatic brain would utter such stupidity? He has further encouraged the fascist criminals in the AKP government with additional platitudes about the USA sharing democratic values with these AKP gangsters. How could you tolerate such tripe from such a high-level representative of our country, Mr. President? How?

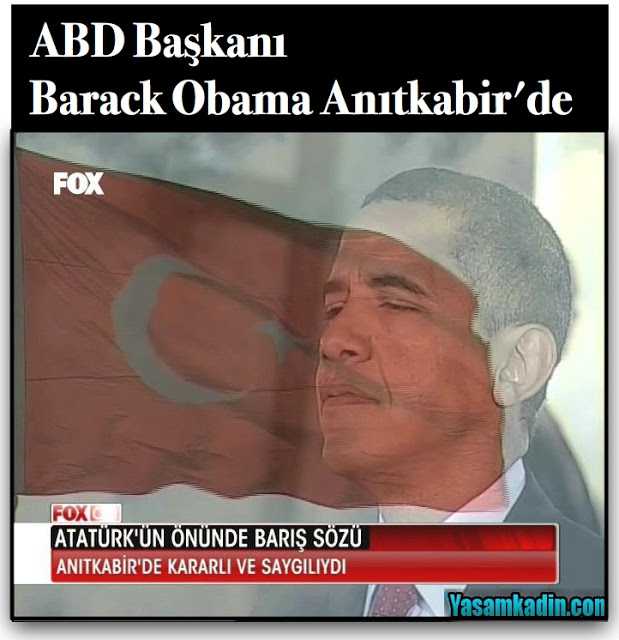

You, on your first visit to Turkey, stood misty-eyed at Atatürk’s grave on April 6, 2009. There and then, you wrote in the guest book that you looked forward to “supporting Ataturk’s vision of Turkey” and “providing ‘peace at home, peace in the world.’” Were these remarks sincere, Mr. President? Perhaps. Or were you lying through your crocodile tears? Perhaps. But the real truth is that your words have indeed proved hollow. You unashamedly embraced and continue to support the repulsive policies of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, policies that have brought disasters at home and chaos in the world. Do you still stand behind your ambassador’s lamentable support for one of the greatest ongoing human rights violations since America’s murderous antics with Pinochet in Chile forty years ago? Would you dare return to Turkey and repeat your past words about Mustafa Kemal Atatürk? I doubt it. The roof at Anıkabir would crash on your head. Do you still believe that a violent government like AKP, rotten to its core with human rights violations, shares America’s values? Given America’s “values” over the past ten years as applied to Turkey and the world you probably do. But do you know what you are supporting?

In less than a decade, the ruling party has imposed the shadow of the dark cloud of sharia over the land. The largest budget item is for the Ministry of Religious Affairs. Mosques and mini-mosques (mescit) are everywhere. Sounds spiritual doesn’t it? Well imagine what would happen in one of the occupying power’s land, say in America, if every theater, ballpark, shopping mall and school had a prayer chapel? That’s a bit much for a secular country like America to deal with, isn’t it? Sure it is. But that’s what the government of Turkey imposes on it’s own soon-to-collapse secular nation.

Moreover, early morning knocks-on-the-door have imprisoned thousands opposed to this government. All opposition are called terrorists and bounced into jail by Erdoğan’s kangaroo courts. University rectors have been defamed and deposed, replaced by government-friendly yes-men and yes-women. Same for the faculty members. Oh, and freedom of speech on campus or anywhere else? None!

You, a constitutional lawyer by training, know well that every democracy requires an independent judiciary. Not so in Turkey. Evidence is ill-gotten and completely tainted. Witnesses give secret, unsworn testimony. Those accused spend years and years in prison while “evidence” is gathered and contaminated. There is no effective, or even ineffective, law of habeas corpus. Judges and prosecutors are clients of the ruling party, in effect, the prime minister. Defense counsels are routinely punished and even arrested for making procedural objections in court.

You also know that a free press provides a vital protection against an abusive government. But not here, Mr. President. Except for a few minor and heroic exceptions, Turkey’s press and media is completely government-controlled. The prime minister tells the corrupt media bosses who to fire and who to hire. It is a sick joke, another travesty of justice. Yet most of the Turks read and watch the government’s puppet media. This speaks to the other requirement for democracy—the necessity to have an informed electorate. Forget that too in Turkey. More journalists are in jail in Turkey than anywhere in the world, including China and Iran.

As most people know, except perhaps Americans, Turkey occupies a dangerous spot in the world. For centuries, religious extremists have been imposing sharia governments on the citizens. Since Turkey became a secular state in 1923, it has been beset by these destructive religious elements. Hence the historic need for a strong army to protect itself from these dark external and internal forces. But now, since the dark forces have taken over the government, there is no longer a need for such an army. Why? Because the Islamo-Fascist conspired to destroy the staunchly secular Turkish military. In a series of ridiculously implausible conspiracies worthy of an Adolph Hitler, the army’s generals have been jailed and replaced by government-friendly hacks. And since the nation is already under occupation by religious extremists, the historical internal security responsibilities for the military have been eliminated by the parliament. Amazingly, the major opposition party voted in agreement. And who now has the responsibility for internal security? The thoroughly violent, completely nazified police. Turkey is indeed a nation under occupation. The dark forces are consolidating their power. And the young people stand alone facing the oppressive, treasonous government. And to the extent that you and your ambassador continue to provide deadly weapons to its police force, the young people face you too. Believe me, Mr. President, all of you should be worried and careful about this.

Having widely, and illegally, ignored the Turkish Constitution, the fascist government is writing a new one which will dramatically change Turkey to the presidential system (like America’s) and give even more power to the head of government. This is the hope and dream of the current prime minister. He will continue to do what he knows best: demeaning, dividing, lying, scheming, repressing, hating and revenging.

Meanwhile murderous cops go free. Thousands of protestors (now known as terrorists) are in jail under unspeakably disgusting conditions. Every public assembly is considered a terrorist gathering. So-called “civilian police,” more accurately described as Hitler-Brownshirts, roam the streets with scimitars, meat cleavers, clubs and knives. This unspeakable, genuine terror has the full support of the prime minister. In fact, they are “his people,” AKP street thugs. And, in case you are wondering, the actual police are just as bad. The police force is under the de facto control of one of your CIA assets living under protection in rural Pennsylvania. Violence. Violence. Violence. None of this is mentioned by your representative in Ankara either. Nor you for that matter. The world knows, but you don’t? You need much better advisors, Mr. President.

Sadly for humanity, the Erdoğan of Turkey is also sui generis. Stubborn, arrogant, always straight ahead at full speed, the first ten days of the Gezi Park Resistance revealed his true essence in all its ignominy. And so it continues with rants about conspiracies, plots, name-callings, arrests, an overall disgraceful show of bad government and criminality. Erdoğan may have destroyed everything: the constitutional court, the media, the judicial system, rules of evidence, university independence, social life, the arts, the army and virtually all aspects of what had been the, as you yourself so movingly called it, “Ataturk’s vision of Turkey.” All these things may have been destroyed. But then Erdoğan called Atatürk a drunk. And that will finish him.

These kids have Erdoğan’s number. There is no way he can stand against their dazzling intelligence and creativity. I wish you had been with me in the streets to meet some of them. Then you would fully understand all that I have written. History tells us that fascists are like bulls, going forward ever forward, punishing and restricting and arresting. And at their end, they blabber into the wind and get their ravings blown back into their faces twice as hard. Turkey is now at that point. You may have noticed this, Mr. President. That’s why when the end comes for fascists, they fold up like cheap suits, their distorted world and their faults reeking of their doom. They, the fascists, are few, and the people, in Turkey’s case, the UNIFIED young people, who chant proudly that they are Mustafa Kemal’s soldiers, are many. And remember, Mr. President, both in the arena and out, the bull never wins.

Sincerely yours,

James (Cem) Ryan, Ph.D.

28 July 2013

Istanbul, Turkey

“We are the soldiers of Mustafa Kemal!”

BRIEF BIO:

James (Cem) Ryan was born and raised in The Bronx, New York City. A graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, he holds

advanced degrees in economics and English literature, a Master of Fine Arts degree from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in literature. He is a proponent for peace and founder of West Point Graduates Against the War: http://www.wpgaw.org/ and Service Academy Graduates Against the War:

PREVIOUS

LETTERS TO PRESIDENT OBAMA: