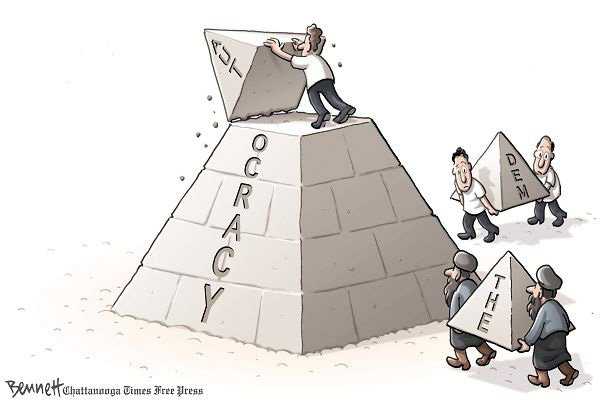

The Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) “democratization package” was announced by Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan on Monday, October 1. The package offers various improvements regarding the rights of non-Muslim minorities, subordinated groups and Kurds as well as readjustments of ongoing state-society relations. Erdogan claimed that this historically important package will not be a “final point” in the country’s journey towards democracy and that it is open to revision.

Since May 31 when the “Gezi resistance” began, the existing paradigms of social relations in Turkey have been controversially mutating. Individuals who attached their political subjectivities to Gezi in varying ways claim to have launched a “resistance” against the “authoritarian” tendencies of the AKP in general and Prime Minister Erdogan in particular. Many groups called for a collective mobilization against the government for the overthrow of the existing political status quo, turning to a “Gezi spirit” expressing a yearning for some kind of “revolution”.

A huge variety of groups including Turkish nationalists, far-right extremists, leftists, secularists and anti-capitalist Muslims gathered under the heading of this “Gezi spirit”. The following months witnessed the attempts to mobilize the masses for an organized uprising against the AKP, which seems to have failed. As previously argued in my piece on the agents of resistance at Gezi Park, one of the reasons for this failure is the gulf between these activists and the more underprivileged, lower classes of society. As sociologist Caglar Keyder alsopoints out, Gezi announces the emergence of a newly visible “new middle class” with a distinct sense of society, individuality and the world; a generation which inherits its social-cultural capital from previous generations with middle/upper-middle class, secular and Kemalist roots.

Yet what may not have been expected by this new middle class after the Gezi resistance was that the AKP would embrace their own “revolutionary” paradigm for reshaping social and political dynamics in Turkey. Just one month into the events of the Gezi resistance, AKP headquarters published a book entitled The Silent Revolution (Sessiz Devrim), to be distributed not publicly but to the party’s organizations throughout the country.

The book cites the policies undertaken by the AKP for the last 11 years, focusing particularly on their struggle with the military establishment leading to a radical transformation of centre-periphery relations, as well as the reform of healthcare to create greater social equality and all sorts of social policy aimed at raising the level of welfare among the middle classes and the suburban poor.

Several AKP deputies had already claimed that the AKP’s policies constituted a “silent revolution” (a concept drawing on Gramscian analysis of hegemony and ‘passive revolution’). But these claims that a revolution is under way had not been heard since the 2011 general elections. Since then there has been unremitting criticism of the authoritarianism of the AKP.

The Gezi resistance has undoubtedly triggered the AKP’s ambition to be seen once again to embrace democratic policies and radical reforms. Therefore, the Gezi resistance must claim to have been successful in two regards: first, ecologically, in saving the green space in Gezi Park from the fate of being replaced by a shopping mall; and second, by forcing the AKP to take the bold steps towards democratization, announced last Monday.

Transforming language

The democratization package includes minor yet revolutionary steps towards democratization since it aims to go beyond the “taboos” set forth by the official republican ideology, inscribed in the foundational mission statement of the Turkish nation-state. Primary school students are no longer obliged to read the “Student Oath” every morning which goes as follows:

“I am a Turk, honest and hardworking. My principle is … to love my homeland and my nation more than my essence. … Oh Great Atatürk ! On the path that you have paved, I swear to walk incessantly toward the aims that you have set. My existence shall be dedicated to the Turkish existence. How happy is the one who says “I am a Turk !”

This nationalist and militarist narrative was a special obstacle for students of different ethnic backgrounds such as Kurds, Circassians, and Arabs, since it was designed to turn them into the obedient subjects of the nation-state, ready to sacrifice himself/herself for the Turkish race and Ataturk, the founder of the nation-state.

Complementary to the abolition of the oath, private institutions are now allowed to facilitate education in various mother tongues. Since the language of education was entirely confined to Turkish, this particular step has an historic importance in going beyond the taboos of the nation-state. The letters W-Q-X which belong to the Kurdish alphabet, for example, were prohibited by the state, which ordered the strict use of Turkish alphabet. Under these linguistic reforms, for instance, Kurdish parents will be able to name their children as they wish.

This transformation of “language” also restores the original names in the Kurdish and Armenian language banned under republican ideology of the villages and towns in Turkey. But permitting “state institutions” to undertake primary and high school education in different mother tongues is still missing from the current democratization package. The necessary adjustments have yet to be made in the constitutional law to reform the whole education system along multi-ethnic lines.

Emancipating the public space

From the time it was formed, the AKP has received immense public support for tackling the politics of the headscarf ban in Turkey. Women who wear headscarves, due to the “militant laicism” inherent in the foundational principles of the official ideology, were not allowed to work in public offices including universities, which entailed thousands of cases of human rights violations. The democratization package offers steps to be taken against such human rights violations and allows women to work in public institutions in their headscarves. Excepted from this reform, however, are those who work as judges, prosecutors, police officers and members of the army. The AKP has failed to offer a total abolition of the ban by leaving these important public institutions out of the headscarf reform.

“Hate speech” and “hate crimes” have been brought into this legislation, with judicial measures to be taken against individuals who discriminate against a person or a group of people for their ethnicity, religious beliefs and lifestyles. Yet the reform act does not mention “women” and “LGBTT” individuals amongst the groups suffering from discrimination on the basis of gender and sexual orientation. Here the criticism of the conservative AKP for being inherently “patriarchal” has been vocal. The law however, will hopefully be useful for the discrimination against women and LGBTT individuals in due course. For now it is up to civil society to form pressure groups so that the legal adjustments can be made on behalf of all underprivileged social classes; Muslim women wearing headscarves, women experiencing male violence, LGBTT individuals oppressed for their sexual orientation, Kurds, Armenians, Alevis and other ethnic/religious groups, who have been victims of discrimination and repression.

The democratization package also includes several reform acts for non-Muslim minorities. The lands of the “Mor Gabriel Monastery” will be returned to the Syriac Christian community foundation. An educational institution dedicated to the language and culture of the “Roma people” has been founded to begin to deal with their problems. While these are necessary steps towards democratization in terms of the rights of minorities, “The Halki Seminary”, which was the main school of theology of Eastern Orthodox Church’s Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, still remains banned from the list of religious facilities. The high expectations on the part of non-Muslims and democrats for the abolition of this ban led to huge disappointment. Erdogan, who during his declaration of the democratization package asserted that, “the rights of people cannot be subjected to any kinds of negotiation”, contradicts himself when the AKP waits for a response from Greek authorities to opening of a mosque in Athens, before they make any attempt to recognise the Halki Seminary. The opening of the Halki Seminary could have facilitated a dialogue between religions and paved the way for Orthodox Christians in Turkey to educate their religious staff; which could only further democratization. The opening of Halki Seminary is an important benchmark for the state’s ability to transform itself from the “militant laicism” which aims to oppress religious multiplicity in the public space, to an Anglo-Saxon type of secularism, in which the state apparatus guarantees citizens’ rights to religious expression and freedom.

There was a further huge disappointment for the Alevi people who were completely left out of the democratization package. Alevism has historically been left out of the official discourse and considered in opposition to the Sunni sect of Islam. Alevis traditionally worship in places called “Cemevi”, different from the mosques of other Islamic sects. Alevis still have no official permission for opening Cemevi in their neighbourhoods, which are not “officially” recognized as places of worship by the Presidency of Religious Affairs. Additionally since Alevi people do not feast during Ramadan, they face various kinds of discrimination in public space as they are considered “heretics” who have fallen away from Islam.

The cultural and state-based discrimination of the Alevi people should have been on the agenda for the democratization package to prevent their further alienation. The only step taken was the change of the name of Nevsehir University into “Haji Bektash Veli” University; named after an influential Alevi mystic and philosopher from the 13th century. Though this particular step seems thinly “symbolic” at best, the AKP deputies declare that they will be announcing another democratization package for the Alevi people soon. The Alevis constitute a large population who in general do not vote AKP, and so far this democratization package offers nothing which suggests that the AKP is attempting to win over this significant slice of the other “50%” of non-AKP supporters.

“Yes, but not enough”

Several groups associated with the “Gezi spirit”, especially the nationalist-Kemalists, have been furiously protesting against this package of measures. Rather than considering the headscarf reform as a step towards equal participation in the public sphere and freedom of lifestyle, Kemalist groups who are dedicated to the official ideology of the Turkish nation-state protest against the permitting of headscarves into public offices, and argue that this is part of a concerted AKP effort to convert the country into an Islamic state. The leaders of opposition parties such as the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and Republican People’s Party (CHP) have protested against the abolition of the “student oath”, claiming that the AKP aims with this move to eliminate republican-nationalist ideals. The reform acts towards Kurdish language and other ethnic-groups have met similar protests by these oppositional groups.

Constructing this particular paranoia, by carefully aiming to consolidate the taboo subjects of the official ideology, the parties in opposition and their supporters are indeed reacting directly against the “Gezi spirit”, which waslibertarian in form and content. The AKP’s embrace of their ‘silent revolution’ in the name of democracy has once again exposed and wrong-footed those social classes who resist change and resent the gradual transformation of the status of various underprivileged groups in society. It also shows us that the “Gezi spirit” was heterogeneous and that not every participant was motivated by the impulse to transform the relations of subordination and oppression in Turkey. Some were rather motivated by reaction against the AKP, who had already taken some bold steps towards Turkey’s democratization.

On previous occasions, the Turkish people have declared,“Yes, but not enough”, regarding AKP reforms, and once again it is clear that this package includes minor yet important steps for democratization. These steps should not be regarded as a “gift” from the AKP or Erdogan to our society; they rather point to the success of our civil society in putting pressure on the AKP to democratize the country. They have been forced to take on the totalitarian tendencies of those social classes who internalize and would like to legitimize the structures of discrimination and domination, reproducing the nationalist, militant-laicist and militarist motives of the official ideology. The opposition parties representative of such classes constitute a hegemonic bloc which strictly supports “the first republic”, when what we need is to extend the scope of democratization with a critical approach capable of ushering in what is nowadays referred to as “the second republic”.

The word “revolution” is frequently used to describe this transition from the totalitarian discourses of the nation-state towards a multicultural society which truly respects each other’s differences. Considering the attempts by the opposition parties who insistently oppose democratization, we need the active participation of a civil society that is motivated by an anti-militarist, multi-culturalist and libertarian vision, to oversee the emergence of a democratization process that can be practiced on a sustainable basis.

The active participation of civil society will be key to Turkey’s progress towards an “open society” in forming successive pressure groups that will continue to impel the AKP into further democratic advance. But in dealing with a wide range of social taboos, we have a long way to go, on a journey which takes us safely far beyond AKP patriarchy, “Aleviphobia”, and those social classes opposed to the AKP who have their own totalitarian tendencies, who are calling for the restoration of the first republic. All we have to do, however, is to show that a “third way” centered on libertarian and democratic politics, is possible.

ISTANBUL—Turkey’s government removed 20 top prosecutors from their posts and cleared the way to investigate three others, in a new sign that Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan is gaining the upper hand in a political power struggle.

ISTANBUL—Turkey’s government removed 20 top prosecutors from their posts and cleared the way to investigate three others, in a new sign that Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan is gaining the upper hand in a political power struggle.