For the first time in 95 years liturgy and hymns were heard on Lake Van

by Tatul Hakobyan

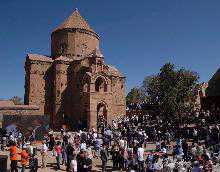

Van, Turkey – As Armenian clergy led by acting Istanbul Patriarch Aram Ateshyan were ringing the bells and making their way from the half-destroyed bell-tower to the Church of Holy Cross to hold a divine liturgy there for the first time in 95 years, several hundred mostly Turkish Armenians walked around the church, looked out towards the lake, lit candles and cried.

An older man kneeled before the church walls and silently prayed and cried with his eyes to the sky.

A middle-aged woman kept trying to light a candle but couldn’t with her hands trembling as she cried.

Another woman walked between cracked khachkars (cross-stones) lying here and there in the church yard and cried with her entire body shaking.

But the Church of Holy Cross (Surb Khach in Armenian) deserves more Armenian tears, more prayers and more believers. The Van Lake (or the Van Sea as Armenians call it), its azure waves have long yearned for Armenian eyes.

But the Church of Holy Cross (Surb Khach in Armenian) deserves more Armenian tears, more prayers and more believers. The Van Lake (or the Van Sea as Armenians call it), its azure waves have long yearned for Armenian eyes.

By noon on September 19 only several dozen Armenians from Armenia arrived here with the same number coming from Diaspora.

The many who were expected to come but did not must have heeded the calls of Armenian authorities and the Armenian Church (both Echmiadzin and Cilicia, as well as the Jerusalem Patriarchate) who urged Armenians not to go to Akhtamar on this day, September 19, not to participate in a “Turkish show.”

But this was far from being show. Anyone on Akhtamar that day felt the energy, the magnetism of the place that dominated everywhere on the island. This was no show. This was a collective prayer for the souls of innocent victims of 1915, even though Archbishop Aram did not specifically mention them.

Last time a liturgy at the Church of Holy Cross was performed in 1915, shortly before the final expulsion of Armenians from this area during the Genocide. Ninety-five years later, a liturgy was heard, but in spite of promises by Turkish officials, the church’s dome was still missing its cross.

Armenian secular and religious leaders called for a boycott after it became clear that a cross would not be installed in time for the ceremony. So, most Armenians who arrived from Armenia were journalists, many of whom came with financial support of various international organizations.

Diaspora media did not dispatch journalists to Akhtamar even though the Turkish Prime Minister’s office sent invitations offering to take up all of their expenses.

Kapriel Chemberjian, who lives in Syria and is a director of the Punik (Phoenix) benevolent fund, has been to Akhtamar and Western Armenia before. This time he arrived with his wife. While he agrees with Armenia’s official boycott, he also believes it is natural for Armenians from all over the world to want to come to a liturgy at a place so sacred for Armenians.

“This is our land, and we should be able to come here whenever we want, as pilgrims, to light a candle,” said Chemberjian, who is also one of the contributors to reconstruction of the Diyarbakir (Tigranakert) church and other Armenian undertakings.

Businessman Dikran Chiderjian who lives in Monaco has also been to Western Armenia before. Together with his French wife he was here in the late 1990s.

“Several years ago a liturgy at the Holy Cross would seem like a dream. Perhaps not everything was properly prepared, but this is an important step towards reclaiming our heritage,” said 70-year-old Chiterchian.

The day before he crisscrossed the lake on a boat visiting other largely destroyed Armenian monuments in this area that have been abandoned for nearly a century.

“[Reasons provided for] Echmiadzin’s refusal to dispatch representatives to the ceremony were merely a cover, real reasons are political,” Chiderjian says.

Armen Yarmayan, 62, is a trustee of the Holy Savior hospital in Istanbul.

“I came to hear a liturgy that is taking place here for the first time since 1915,” he said. According to Yarmayan, Armenia’s boycott is justified, but Turks too should not be blamed for not installing the cross.

“Time will put everything in its place, the cross will be installed and believers from Armenia will come to the next liturgy,” he predicted.

Krikor Kyokchian was born in Istanbul, but lives in Beirut. He came to Akhtamar with four members of his family to be here, as he said, on an historic day.

“Let there be ten boycotts, I would have come here anyway, I needed to see this for myself,” he said.

The Church of Holy Cross was built in the early 10th century in the times of Gagik the First Artsruni, King of Vaspurakan. Designed by architect Manvel the church served as the Catholicosal residence adjacent to the Artsruni court. Due to politics of the period, five Catholicoses resided at Akhtamar during the 10th century.

As conditions in the Ararat valley more or less normalized, Catholicos moved to the Church of Argina in Ani. Since then the Holy Cross was no longer a residence for the Catholicos of All Armenians. But to preserve that memory, Akhtamar’s clerical brotherhood continued to call their leaders Catholicoses.

So it turns out that 10th century Armenians were able to create a cultural monument of world heritage value, but 21st century Turks are “unable” to install a cross on top of it.

They claim that either there was not enough time, or the cross was too heavy, or wonder how could they have a cross in a Muslim country, and then quickly add that the cross would go up a week after the ceremony.

If this is a possible to do a week later, why not do it before the liturgy, to make sure that more people come, including from Armenia?

The cross, which by the way weighs not 200 kilos as some Turks claimed, citing that as a reason why it may damage the dome, but just 76 kilos, could be seen standing not far from the church.

In March 2007, following its restoration, the Church of Holy Cross was opened as a museum with a prohibition that it be used for religious ceremonies. Armenian officials, including deputy minister of culture, were present at that opening.

As part of that ceremony, a huge Turkish flag was unfurled on the island and that was truly a show.

This time there wasn’t anything like that. Other than a single blood-red flag with a crescent in the Akhtamar bay, on September 19 one would be hard-pressed to find Turkish symbols on the island.

Nevertheless, helicopters circling in the air, and a boat with armed soldiers seen in the lake throughout the ceremony, did serve as reminders that this was a state-planned event, in a way a “show.”

Among the guests one could see the governor of Van province and the mayor of Van, as well as foreign diplomats accredited in Ankara.

Van governor did all he could to ensure a larger turnout through participation of local residents. During the liturgy Muslim Turks and Kurds outnumbered Armenians several times. Some of them came out of curiosity, others for a weekend getaway on the shores of Van.

“Dear Armenian friends, welcome to Van,” a poster announced near the entrance to the city. But no other writings could be seen that would identify the Akhtamar Church as Armenian, and term Armenian seemed to be studiously avoided.

But on September 17 several pages of the local Van newspaper were published in Western Armenian, produced in cooperation with Istanbul-based Agos. They included a feature on “What happened with monasteries of Van” that listed about a hundred monuments located on the shores of the lake, most of them now destroyed and some still partly intact, all abandoned.

Turkish Armenians say that the Church of Holy Cross will soon have its cross installed. They say that 10 to 15 years ago they would not even dare to think of its reconstruction or about having a divine liturgy here, even without a cross in place. They see the September 19 ceremony as not completely satisfactory, but still an important milestone in the life of their community.

Akhtamar and its Church of the Holy Cross deserve to see more Armenians come, more Armenians crying, praying and walking around.

Our Lake Van, its azure waves have long yearned for Armenian eyes.

— Journalist Tatul Hakobyan is an expert with the Civilitas Foundation. From 2006 to 2009, he was the Armenian Reporter’s senior correspondent. He is the author of “Artsakh Diary: Green and Black,” a book about the Karabakh war published in Armenian, English and Russian. He will soon publish his second book “View from Ararat: Armenians and Turks.”

(c) 2010 Armenian Reporter