Hakan Fidan Takes Independent Tack in Wake of Arab Spring

- By

- ADAM ENTOUS

- JOE PARKINSON

in Washington and

in Istanbul

![Turkey's Spymaster Plots Own Course on Syria 2 [image]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/P1-BN482_USTURK_G_20131009222734.jpg) Official White House Photo by Pete SouzaPresident Obama and John Kerry met with Turkish Prime Minister Erdogan and Turkish intelligence chief Fidan, second and third from left, in May.

Official White House Photo by Pete SouzaPresident Obama and John Kerry met with Turkish Prime Minister Erdogan and Turkish intelligence chief Fidan, second and third from left, in May.

On a rainy May day, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan led two of his closest advisers into the Oval Office for what both sides knew would be a difficult meeting.

It was the first face-to-face between Mr. Erdogan and President Barack Obama in almost a year. Mr. Obama delivered what U.S. officials describe as an unusually blunt message: The U.S. believed Turkey was letting arms and fighters flow into Syria indiscriminately and sometimes to the wrong rebels, including anti-Western jihadists.

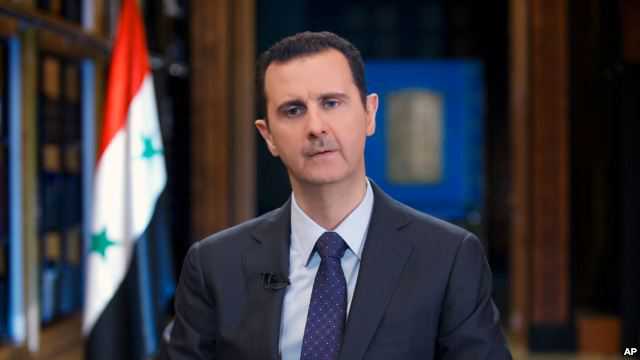

Seated at Mr. Erdogan’s side was the man at the center of what caused the U.S.’s unease, Hakan Fidan, Turkey’s powerful spymaster and a driving force behind its efforts to supply the rebels and topple Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

In the wake of the Arab Spring uprisings, Mr. Fidan, little known outside of the Middle East, has emerged as a key architect of a Turkish regional-security strategy that has tilted the interests of the longtime U.S. ally in ways sometimes counter to those of the U.S.

“Hakan Fidan is the face of the new Middle East,” says James Jeffrey, who recently served as U.S. ambassador in Turkey and Iraq. “We need to work with him because he can get the job done,” he says. “But we shouldn’t assume he is a knee-jerk friend of the United States, because he is not.”

Mr. Fidan is one of three spy chiefs jostling to help their countries fill a leadership vacuum created by the upheaval and by America’s tentative approach to much of the region.

One of his counterparts is Prince Bandar bin Sultan al-Saud, Saudi Arabia’s intelligence chief, who has joined forces with the Central Intelligence Agency in Syria but who has complicated U.S. policy in Egypt by supporting a military takeover there. The other is Iran’s Maj. Gen. Qasem Soleimani, commander-in-chief of the Quds Forces, the branch of the elite Revolutionary Guard Corps that operates outside of Iran and whose direct military support for Mr. Assad has helped keep him in power.

Meet the Middle East’s spymasters. Dubai real estate-palooza. Divers assess the Lampedusa wreck. WSJ tracks stories from around the world in The Foreign Bureau. Photo: Associated Press

Mr. Fidan’s rise to prominence has accompanied a notable erosion in U.S. influence over Turkey. Washington long had cozy relations with Turkey’s military, the second-largest army in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. But Turkey’s generals are now subservient to Mr. Erdogan and his closest advisers, Mr. Fidan and Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, who are using the Arab Spring to shift Turkey’s focus toward expanding its regional leadership, say current and former U.S. officials.

Mr. Fidan, 45 years old, didn’t respond to requests for an interview. Mr. Erdogan’s office declined to elaborate on his relationship with Mr. Fidan.

The U.S. and Turkey are clashing over Syria, complicating U.S. efforts and highlighting how Middle East turmoil is upending longstanding alliances. Adam Entous reports. Photo: AP.

At the White House meeting, the Turks pushed back at the suggestion that they were aiding radicals and sought to enlist the U.S. to aggressively arm the opposition, the U.S. officials briefed on the discussions say. Turkish officials this year have used meetings like this to tell the Obama administration that its insistence on a smaller-scale effort to arm the opposition hobbled the drive to unseat Mr. Assad, Turkish and U.S. officials say.

Mr. Fidan is the prime minister’s chief implementer.

Since he took over Turkey’s national-intelligence apparatus, the Milli Istihbarat Teskilati, or MIT, in 2010, Mr. Fidan has shifted the agency’s focus to match Mr. Erdogan’s.

His growing role has met a mixture of alarm, suspicion and grudging respect in Washington, where officials see him as a reliable surrogate for Mr. Erdogan in dealing with broader regional issues—the futures of Egypt, Libya and Syria, among them—that the Arab Spring has brought to the bilateral table.

Mr. Fidan raised concerns three years ago, senior U.S. officials say, when he rattled Turkey’s allies by allegedly passing to Iran sensitive intelligence collected by the U.S. and Israel.

More recently, Turkey’s Syria approach, carried out by Mr. Fidan, has put it at odds with the U.S. Both countries want Mr. Assad gone. But Turkish officials have told the Americans they see an aggressive international arming effort as the best way. The cautious U.S. approach reflects the priority it places on ensuring that arms don’t go to the jihadi groups that many U.S. officials see as a bigger threat to American interests than Mr. Assad.

U.S. intelligence agencies believe Mr. Fidan doesn’t aim to undercut the U.S. but to advance Mr. Erdogan’s interests. In recent months, as radical Islamists expanded into northern Syria along the Turkish border, Turkish officials have begun to recalibrate their policy—concerned not about U.S. complaints but about the threat to Turkey’s security, say U.S. and Turkish officials.

There is no doubt in Turkey where the spymaster stands. Mr. Fidan is “the No. 2 man in Turkey,” says Emre Uslu, a Turkish intelligence analyst who writes for a conservative daily. “He’s much more powerful than any minister and much more powerful than President Abdullah Gul.”

Still, he cuts a modest figure. Current and former Turkish officials describe him as gentle and unpretentious. In U.S. meetings, he wears dark suits and is soft-spoken, say U.S. officials who have met him repeatedly and contrast him with Prince Bandar, the swashbuckling Saudi intelligence chief.

“He’s not Bandar,” one of the officials says. “No big cigars, no fancy suits, no dark glasses. He’s not flamboyant.”

Mr. Fidan’s ascension is remarkable in part because he is a former noncommissioned officer in the Turkish military, a class that usually doesn’t advance to prominent roles in the armed forces, business or government.

Mr. Fidan earned a bachelor of science degree in government and politics from the European division of the University of Maryland University College and a doctorate in political science from Ankara’s elite Bilkent University. In 2003, he was appointed to head Turkey’s international-development agency.

He joined Mr. Erdogan’s office as a foreign-policy adviser in 2007. Three years later, he was head of intelligence.

“He is my secret keeper. He is the state’s secret keeper,” Mr. Erdogan said of his intelligence chief in 2012 in comments to reporters.

Mr. Fidan’s rise at Mr. Erdogan’s side has been met with some concern in Washington and Israel because of his role in shaping Iran policy. One senior Israeli official says it became clear to Israel that Mr. Fidan was “not an enemy of Iran.” And mistrust already marked relations between the U.S. and Turkish intelligence agencies. The CIA spies on Turkey and the MIT runs an aggressive counterintelligence campaign against the CIA, say current and former U.S. officials.

The tension was aggravated in 2010 when the CIA began to suspect the MIT under Mr. Fidan of passing intelligence to Iran.

At the time, Mr. Erdogan was trying to improve ties with Tehran, a central plank of Ankara’s “zero problems with neighbors” policy. U.S. officials believe the MIT under Mr. Fidan passed several pieces of intelligence to Iran, including classified U.S. assessments about the Iranian government, say current and former senior U.S. and Middle Eastern officials.

U.S. officials say they don’t know why Mr. Fidan allegedly shared the intelligence, but suspect his goal was relationship-building. After the Arab Spring heightened tensions, Mr. Erdogan pulled back from his embrace of Tehran, at which point U.S. officials believe Mr. Fidan did so, too.

Officials at the MIT and Turkey’s foreign ministry declined to comment on the allegations.

In 2012, Mr. Fidan began expanding the MIT’s power by taking control of Turkey’s once-dominant military-intelligence service. Many top generals with close ties to the U.S. were jailed as part of a mass trial and convicted this year of plotting to topple Mr. Erdogan’s government. At the Pentagon, the jail sentences were seen as the coup de grace for the military’s status within the Turkish system.

Mr. Fidan’s anti-Assad campaign harks to August 2011, when Mr. Erdogan called for Mr. Assad to step down. Mr. Fidan later started directing a secret effort to bolster rebel capabilities by allowing arms, money and logistical support to funnel into northern Syria—including arms from Saudi Arabia, Qatar and other Gulf allies—current and former U.S. officials say.

Mr. Erdogan wanted to remove Mr. Assad not only to replace a hostile regime on Turkey’s borders but also to scuttle the prospect of a Kurdish state emerging from Syria’s oil-rich northeast, political analysts say.

Providing aid through the MIT, a decision that came in early 2012, ensured Mr. Erdogan’s office had control over the effort and that it would be relatively invisible, say current and former U.S. officials.

Syrian opposition leaders, American officials and Middle Eastern diplomats who worked with Mr. Fidan say the MIT acted like a “traffic cop” that arranged weapons drops and let convoys through checkpoints along Turkey’s 565-mile border with Syria.

Some moderate Syrian opposition leaders say they immediately saw that arms shipments bypassed them and went to groups linked to the Muslim Brotherhood. Mr. Erdogan’s Islamist-rooted Justice and Development Party has supported Muslim Brotherhood movements across the region.

Syrian Kurdish leaders, meanwhile, charge that Ankara allowed arms and support to reach radical groups that could check the expanding power of Kurdish militia aligned with Turkey’s militant Kurdistan Workers’ Party.

Turkish border guards repeatedly let groups of radical fighters cross into Syria to fight Kurdish brigades, says Salih Muslim, co-chairman of the Democratic Union of Syria, Turkey’s most powerful Kurdish party. He says Turkish ambulances near the border picked up wounded fighters from Jabhat al Nusra, an anti-Assad group linked to al Qaeda. Turkish officials deny those claims.

Opposition lawmakers from the border province of Hatay say Turkish authorities transported Islamist fighters to frontier villages and let fighter-filled planes land at Hatay airport. Turkish officials deny both allegations.

Mehmet Ali Ediboglu, a lawmaker for Hatay’s largest city, Antakya, and a member of the parliament’s foreign-relations committee, says he followed a convoy of more than 50 buses carrying radical fighters and accompanied by 10 police vehicles to the border village of Guvecci. “This was just one incident of many,” he says. Voters in his district strongly oppose Turkish support for the Syrian opposition. Turkish officials deny Mr. Ediboglu’s account.

In meetings with American officials and Syrian opposition leaders, Turkish officials said the threat posed by Jabhat al Nusra, the anti-Assad group, could be dealt with later, say U.S. officials and Syrian opposition leaders.

The U.S. added Nusra to its terror list in December, in part to send a message to Ankara about the need to more tightly control the arms flow, say officials involved in the internal discussions.

The May 2013 White House encounter came at a time when Mr. Obama had grown increasingly uncomfortable with the Turkish leader’s policies relating to Syria, Israel and press freedoms, say current and former U.S. officials.

Mr. Obama told the Turkish leaders he wanted a close relationship, but he voiced concerns about Turkey’s approach to arming the opposition. The goal was to convince the Turks that “not all fighters are good fighters” and that the Islamist threat could harm the wider region, says a senior U.S. official.

This year, Turkey has dialed back on its arming efforts as it begins to worry that the influence of extremist rebel groups in Syria might bleed back into Turkey. At Hatay airport, the alleged way station for foreign fighters headed to Syria, the flow has markedly decreased, says a representative of a service company working at the airport.

In September, Turkey temporarily shut part of its border after fighting erupted between moderate Syrian rebels and an Iraqi al Qaeda outfit, the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham. Turkish President Gul warned that “radical groups are a big worry when it comes to our security.”

In recent months, Turkish officials have told U.S. counterparts that they believe the lack of American support for the opposition has fueled extremism because front-line brigades believe the West has abandoned them, say U.S. and Turkish officials involved in the discussions.

In September, Mr. Davutoglu, the foreign minister, met Secretary of State John Kerry, telling him Turkey was concerned about extremists along the Syrian border, say U.S. and Turkish officials. The Turks wanted Mr. Kerry to affirm that the U.S. remained committed to the Syrian opposition, say U.S. officials.

Mr. Kerry told Turkish officials the U.S. was committed but made clear, a senior administration official says of the Turkish leaders, that “they need to be supportive of the right people.”

Also in September, Mr. Fidan met with CIA Director John Brennan and Director of National Intelligence James Clapper, say Turkish and U.S. officials, who decline to say what was discussed.

A former senior U.S. intelligence official says Mr. Fidan has built strong relationships with many of his international counterparts. At the same time, a current U.S. intelligence official says, it is clear “we look at the world through different lenses.”

Write to Adam Entous at [email protected] and Joe Parkinson [email protected]

A version of this article appeared October 10, 2013, on page A1 in the U.S. edition of The Wall Street Journal, with the headline: Turkey’s Spymaster Plots Own Course on Syria.