By ALKMAN GRANITSAS and STELIOS BOURAS

ATHENS—Greece has renewed its territorial claims over a broad swath of disputed waters in the eastern Mediterranean where the indebted country hopes to find vast oil and gas deposits—a plan that risks sparking a confrontation with Turkey.

Over the past several weeks, senior government officials have made a series of public statements—both at home and abroad—pointing to an almost two-decade-old international treaty granting those rights, one Greece hasn’t asserted until now. Athens also has been building support in other European capitals and stepping up a diplomatic campaign at the United Nations.

This week, Greek Prime Minister Antonis Samaras broached the topic with his Turkish counterpart, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, in a meeting in Istanbul where he called on Turkey to respect Greece’s rights under international law. So far, Ankara, which says those resources belong to Turkey and has warned for almost 20 years that any effort to draw new boundaries could lead to war, has called for further dialogue.

Mr. Erdogan told Greek state television on Monday that “we’re approaching the issue with hope and without prejudices as we continue to work on territorial waters and Aegean-related matters. So long as the sides approach this matter with goodwill, there’s no reason not to get results.”

For Greece, the stakes are enormous. An estimated €100 billion ($130 billion) of undersea hydrocarbon reserves—if proven—could ease the country’s crippling debt burden and make Greece a significant energy supplier for Europe, which wants to reduce its dependence on Russia. Mounting evidence of those reserves, along with recent moves by Cyprus to assert its own claims, have raised the stakes even further.

Those reserves “will mean, clearly, wealth for Greece, wealth for Europe, a significant improvement in Europe’s energy security and a significant enhancement in Greece’s geopolitical role,” Mr. Samaras said in a recent speech to a business conference.

For now, Greece is proceeding cautiously to avoid confrontation and is using U.N. procedures to gradually build its case. Athens’s end goal is clear: Greece hopes to gain international recognition for the exclusive use of a 200-nautical-mile zone around the country, basing its claims on the fact that it is a signatory to the U.N.’s Law of the Sea treaty and Turkey isn’t.

To date, 165 nations and territories—including the European Union—have ratified the treaty. The U.S., which helped negotiate the pact in the 1980s, hasn’t ratified it but generally recognizes its provisions. Last summer, the Obama administration attempted to pass the treaty through the Senate, but fell one vote short of the two-thirds majority needed.

Athens “is eager to assert its rights, but we don’t want to do anything that creates turbulence in the region,” said a senior Greek government official. “For now, we are proceeding slowly” through legal channels.

One such step came in late January, when Greece’s foreign minister lodged a formal complaint at the U.N. after Turkey said in April that it would issue exploration licenses in a disputed area south of the Greek island of Rhodes.

Turkey has said Greece’s counterclaims “have no basis in international law” and said it would take reciprocal steps at the U.N.

In an interview with a Turkish newspaper this week, Turkish Energy Minister Taner Yildiz said energy issues shouldn’t be a source for tension in bilateral relations and said Ankara had no imminent plans to issue those licenses. “Don’t we know any exploration creates a controversy? Of course we know,” he told the Hurriyet newspaper.

The next move for Greece, government officials said, would likely be another submission to the U.N. formally delineating Greece’s nautical coordinates. That would be a prelude to declaring an exclusive economic zone under the provisions of the sea treaty.

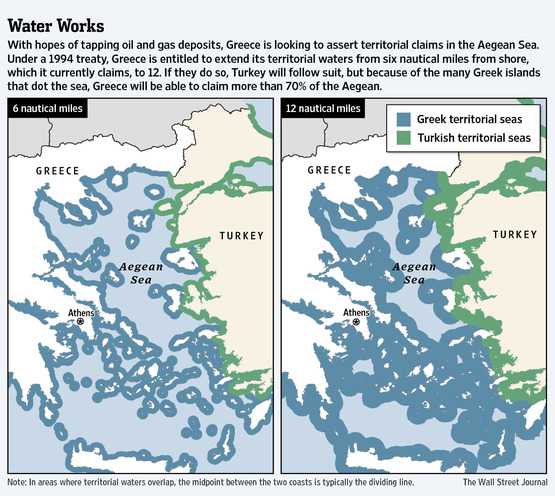

Under terms of the 1994 treaty, Greece is entitled to extend its territorial rights to as many as 12 nautical miles from shore—double the six it now claims—and an exclusive economic zone of as many as 200 miles. Athens has refrained from doing so. In 1995, the year Greece ratified the treaty, Turkey’s parliament declared that any unilateral move to assert such claims would constitute a cause for war.

At issue is the complex geography in the Aegean Sea that separates Greece from Turkey. After the breakup of the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of World War I, Greece was given sovereignty over most of the islands that dot the Aegean and form a continuous archipelago between mainland Greece and Turkey.

Under the present limit, Greece claims more than 40% of the Aegean as its own, compared with less than 10% for Turkey. By widening the limit to 12 miles, more than 70% of the Aegean and its seabed would be in Greek territory. A 200-mile exclusive economic zone would mean Greek claims also stretched far into the Mediterranean—enveloping Turkey—and reaching as far as Cyprus in the southeast.

Geologists believe there are oil and gas deposits in the north Aegean, where drilling first began on a small scale in the early 1980s. More recently, a bonanza gas find off Israel’s coast in 2010, a second find off Cyprus since then, and various surveys have indicated that oil and gas is to be found in the eastern Mediterranean.

Encouraged, Greece began hunting for hydrocarbons late last year in less-contentious areas west and south of the country. The government, which is struggling under a €300 billion debt burden, aims to auction off exploration licenses for those areas toward the end of this year.

In February, French President François Hollande, during a visit to Athens, appeared to back Greece’s position by referring to the country’s legal rights under the Law of the Sea treaty.

“The presence of gas deposits that can, first, be found, and then subsequently exploited, represents an opportunity for Greece and for Europe; and I believe that here, international law, the Law of the Sea, will prevail,” he said.

—Emre Peker in Istanbul contributed to this article.

https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887323978104578332352776971978