Despite harsh rhetoric, Turkey won’t take any action against the Syrian government of Bashar Assad without getting a go-ahead from Washington, Middle East expert, Jeremy Salt, told RT.

Turkish authorities have detained nine people in connection with Saturday’s deadly car bombings in a town near the Syrian border.

Two blasts killed 46 and injured over 100 as Turkey was quick to blame Syrian intelligence for the attack, but the government in Damascus denies all the accusations.

Middle Eastern history and politics professor at Bilkent University in Turkey, Jeremy Salt, says it’s the Islamists among the Syrian rebels, who look the only party to benefit from the attacks.

RT: Why did the Turkish government label the Syrian government as the “usual suspects” in the bombings – before the investigation even started?

Jeremy Salt: The Turkish government claims it arrested nine people and it claims to have evidence that they’re connected with the Syrian intelligence service. We haven’t seen that evidence yet. We’ll have to wait and see what it says. At this stage, it seems to me quite inconceivable that Syria would do that because if we look at what’s happening on the ground right now. The Syrian army is rolling back the insurgency. The insurgents have taken huge losses in the last few months, in particular, around Damascus, near the Lebanese border, and even around Halab – Aleppo – and in the North Syria. And along with this is the fact that the Americans are changing pace and are going into negotiations with Russia to come out with a solution. So it doesn’t make any sense that Syria would do that right now.

RT: Just in the last few hours, Syria’s information minister said that Turkish Prime Minister Erdogan’s responsible for this by playing a “dangerous game with al-Qaeda”. What did he mean by that?

JS: We know for a fact that – because the main Islamist fighting group in Syria has admitted this – al-Qaeda in Iraq and Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria are one in the same. And all the fighting groups in Syria are Islamist and they’re working tactically with Jabhat al-Nusra. So, al-Qaeda is in Syria. We know that. It’s now confirmed, but this was more or less suspected from the start. What we’re seeing now is kind of charge and counter-charge as people try to put the blame for this on to someone else. My feeling about this – and obvious kind of guess is that the party responsible for this is one of the armed groups because if anyone has a reason to try to heat up the situation and drag outside countries it would be them. They’re in very serious problems right now.

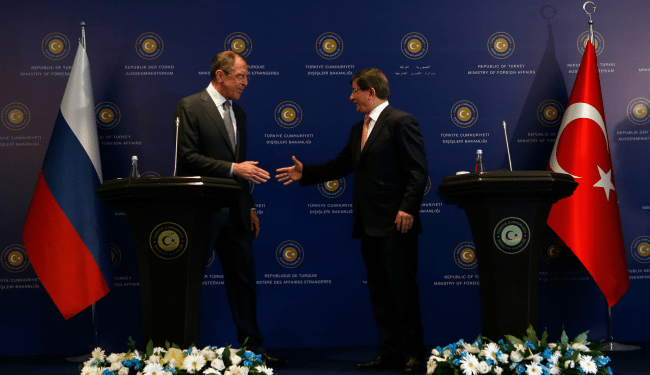

Turkey’s Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. (AFP Photo / Adem Altan)

RT: Turkey’s Interior Minister urged the international community to get involved against Syrian President Assad. Doesn’t this undermine the peace efforts proposed by Russia, US and the UK?

JS: The whole point is that they (the international community) have been deeply involved for more than two years and they haven’t succeeded in their objective, which is ultimately to overthrow the Syrian government – to bring it down. And so they’re still kind of chanting the same refrain, but there’s actually no possibility that the Syrian government can be brought down without direct intervention from outside governments. And the emphasis on Bashar al-Assad takes the emphasis where it should be, which is the Syrian army. Because the Syrian army is fighting – this is a national project. The foot soldiers in the Syrian army are mainly Sunni Muslims and, so, they have a national spirit. And that kind of refrain that the outside government should do more, should send in arms, should declare a no-fly zone are only going to worsen the situation.

What we clearly need now is progress towards negotiating a solution, which is the path Obama has taken. And I think, in spite everything we’ve seen in the last couple of weeks – the chemical weapons propaganda, the Israeli attack – that I don’t think Obama is going allow himself to be drawn into this.

RT: Turkey says it will take “every kind of measure” in response. What could that be?

One has to take it seriously, but the fact is that [Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip] Erdogan is going to Washington this week and Syria will be on top of the agenda and my feeling is that Turkey won’t do anything by itself – that if Obama won’t bite, if he won’t commit America to take a more involved position over Syria, I don’t think that Turkey will do anything.

Now, the key issue here is what kind of evidence are they going to come up with. Will they come up with any evidence that’s going to convince us that this, in fact, was an action carried out by the Syrian intelligence services. So there are many many unknowns right now and, of course, everything is going to depend on the outcome of the talks in Wahington between Obama and Erdogan.

via ‘Turkey won’t act on Syria without US blessing’ — RT Op-Edge.