|

Category: Syria

-

Syria opposition must distance itself from “terrorists:” Germany

-

Syrian rebels told by West to unify and reject extremism

Syrian rebels told by West to unify and reject extremism

Syrian rebels were told by their western backers on Saturday they had to present a united face and reject extremism in return for a major new package of non-lethal assistance.

The West has been reluctant to provide even non-lethal aid to rebel fighters Photo: Reuters

By Richard Spencer, Istanbul

4:05PM BST 20 Apr 2013

Foreign ministers of nations backing the Syrian opposition, including William Hague, the Foreign Secretary, and John Kerry, the US secretary of state, met opposition leaders in Istanbul to thrash out a major new aid package.

They continue to reject directly supplying the opposition with arms, despite fighting reaching a bloody stalemate across the country, but the US was on the verge of announcing up to $200 million in “non-lethal” military aid – equipment such as body armour and night-vision goggles.

Diplomatic sources told The Daily Telegraph that in return the allies were demanding an end to internal wrangling in the opposition Syrian National Coalition, the Western-recognised political front for the rebels.

The SNC was being asked to sign up to a three-pronged pledge. They had to reject extremism and present an inclusive face to the world that included religious minorities, secular groups and women as well as the dominant Islamist faction.

Several secular members of the coalition have walked out in the last month, following the election of Ghassan Hitto, who is seen as close to the Muslim Brotherhood, as an interim prime minister for the rebels.

Related Articles

- Israeli threat to intervene in Syria

18 Apr 2013

- Assad accuses West of ‘backing al-Qaeda’

17 Apr 2013

- West will pay for ‘supporting al-Qaeda’

17 Apr 2013

- Syria: Across the Lines

18 Apr 2013

- Syria: Bashar al-Assad cuts prison sentences

16 Apr 2013

They are also being told to commit to secure Syria’s chemical weapons, a major security concern, and to present a detailed plan for “the day after” – how basic services will be run whenever President Bashar al-Assad is forced from office, assuming he is.

Anti-Syrian regime protesters chant slogans and wave the Syrian revolutionary flag during a demonstration in Aleppo (AP)

Time is running out,” one diplomatic source said, adding that the Coalition needed to show unity to be recognised as a credible leadership by those doing the fighting inside Syria.

On Thursday, Mr Kerry told congressmen: “We want to make certain that the people we’re working with are committed to pluralism, diversity, to a democratic process. There have to be a series of guarantees.”

The West, represented in the “Friends of Syria” group, has been reluctant to provide even non-lethal aid to rebel fighters, keen not to get sucked into another Middle Eastern war and afraid of bolstering the many jihadist forces among the rebels.

But America is believed to be coordinating with Gulf allies like Saudi Arabia, which are sending weapons, and the SNC on Saturday called for more direct intervention. “While humanitarian aid is a dire necessity, the Syrian opposition is also looking for support that will enable the immediate fall of the regime and an end to the suffering of the Syrian people,” a statement said.

Underlining their demands, fierce fighting claims scores of lives on Saturday. Activists and the regime confirmed major battles in the Damascus suburbs and between Homs and the Lebanese border.

In Damascus, regime troops were attacking rebels who had seized the mixed Sunni and Christian suburbs of Jdeidat Artouz and Jdeidet al-Fadel. The activists’ Damascus media office said 69 people had been killed on the rebel side, including civilians.

Near the Lebanese border, an area divided between Sunni, Shia and Christian communities, regime forces swept into four rebel-held villages around the town of Qusayr. Earlier in the week, rebels seized part of an airbase north of Qusayr, showing the back-and-forth nature of the conflict.

- Israeli threat to intervene in Syria

-

Kerry to announce more nonlethal aid for Syrian rebels

By Elise Labott

The Obama administration is set to announce a significant expansion of nonlethal aid to the armed Syrian opposition as the European Union moves closer to lifting an arms embargo to potentially arm rebels battling President Bashar al-Assad, U.S. officials told CNN.

Secretary of State John Kerry is expected to announce the new assistance package at an international meeting on Syria in Istanbul on Saturday, the officials said.

CNN first reported on April 9 that the administration was finalizing a package of increased assistance. The officials said the exact dollar amount and specific items to be shipped have not been finalized, and will be determined in Istanbul, where Kerry is to meet with other donors to Syria and leaders of the Syrian opposition.

However, officials said the package is expected to include more than $100 million in equipment such as body armor, night vision goggles and other military equipment that is defensive in nature, but could be used to aid in combat by Syrian rebels battling forces loyal to al-Assad.

Other options under discussion include assistance to support the expansion of the ongoing, civilian-led programs for delivery of critical goods and services by local councils throughout Syria and additional aid for capacity building efforts, the officials said

Kerry told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Thursday a goal of Friends of Syria meeting is to identify “what accelerants to Assad’s departure might make the most sense.”

Increasing nonlethal aid to the rebels could help convince al-Assad that he must step down, Kerry said.

Another aim of the conference is to “get everybody on the same page” with respect to what a post-Assad Syria will look like,” he said. That could “create a confidence level about who’s getting what kind of aid from whom.”

The move by Washington to expand assistance to the armed rebels reflects what U.S. officials describe as a ramped-up effort to change the military balance on the battlefield in Syria to get al-Assad to step down.

The move comes as Britain and France are leading efforts to lift a European Union arms embargo on Syria.

Both have suggested they are prepared to join nations such as Qatar in providing the rebels with weapons, and are urging the United States to do the same. The arms embargo expires in May and diplomats said the EU countries are discussing possibly allowing it to expire or be amended to ban only weapons for Syrian government forces.

The package being discussed, however, still falls short of the heavy weapons and high tech equipment sought by the rebels.

Despite pressure from Congress and his own national security team, President Barack Obama has been cautious about increasing direct aid for the armed rebels. Kerry has pushed for more aggressive U.S. involvement in Syria since taking office in February.

Last month, Obama agreed to send food and medicine to the rebels, the first direct U.S. support for the armed opposition.

Supporters of expanding the aid argue such a step would strengthen the hand of moderate members of the opposition and make them less reliant on well-armed extremist elements within their ranks.

“Everybody has now accepted a concern about extremist elements who have forced their way into this picture, and there is a desire by all parties to move those extremist elements to the side and to give support, I believe, to the Syrian opposition,” Kerry said Thursday. “That’s a big step forward.”

A push last summer from CIA, Pentagon and State Department leaders was rejected by the White House. At least for now, it remains opposed to arming the opposition, fearing that U.S.-provided weapons could wind up in the wrong hands.

The Obama administration has funneled $385 million in humanitarian aid to Syria through international institutions and nongovernmental organizations.

In addition, Washington has provided more than $100 million to the political opposition and has pressed it to establish a leadership structure.

But the Syrian Opposition Council, the main Syrian opposition group, has roundly criticized the United States for refusing to provide badly-needed support to organize a transitional government and broaden its support inside Syria.

After Istanbul, Kerry will travel to Brussels, where he will discuss the Syria crisis with NATO and EU foreign ministers. He will also meet with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. The Obama administration sees Moscow, one of Syria’s most important backers, as key to a political settlement.

On Thursday, Kerry said Washington was still open to negotiations between the regime and the opposition but warned “that time is not on the side of a political solution. It’s on the side of more violence, more extremism, an enclave breakup of Syria.”

The longer the war drags on, Kerry said, the greater the chance of a “very dangerous sectarian confrontation over the long term, and the potential of really bad people getting hold of chemical weapons,” he added.

Post by: By CNN Foreign Affairs Reporter Elise Labott

Filed under: Assad • Sec. State John Kerry • Syria -

More U.S. Support for Syria Rebels Would Hinge on Pledges to Abide by Law

More U.S. Support for Syria Rebels Would Hinge on Pledges to Abide by Law

By MARK LANDLER and MICHAEL R. GORDON

Published: April 19, 2013

- GOOGLE+

- SAVE

- SHARE

- SINGLE PAGE

- REPRINTS

WASHINGTON — President Obama has agreed to additional nonlethal aid for Syria’s rebels, according to a senior administration official, but its delivery will hinge in part on pledges by their political leaders to be inclusive, to protect minorities and to abide by the rule of law.

Multimedia

Video Feature

WATCHING SYRIA’S WAR

A Father Mourns His Children

-

GRAPHIC: Map of the Dispute in Syria

-

GRAPHIC: An Arms Pipeline to the Syrian Rebels

Related

-

Syria Faces New Claim on Chemical Arms (April 19, 2013)

Connect With Us on Twitter

Follow@nytimesworldfor international breaking news and headlines.

Twitter List: Reporters and Editors

Secretary of State John Kerry planned to meet with opposition leaders in Istanbul on Saturday, as well as with foreign ministers from nations that are supporting them, to discuss both what the United States plans to do to help the rebels and what it expects from them.

“It’s not a quid pro quo, but we want the opposition to do more,” said a senior official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the administration’s strategy. “Secretary Kerry will be discussing what steps we want them to take.”

The meeting in Turkey of the so-called Friends of Syria group is taking place against a backdrop of worsening violence in the two-year-old civil war, dire new worries about how to care for millions of displaced Syrians, and further signs of Islamist radicalization in the insurgency as well as intransigence by President Bashar al-Assad. The special Syria envoy of the Arab League and United Nations, Lakhdar Brahimi, told the Security Council on Friday that “the situation is extremely bad” and that he thinks daily about resigning.

The American package, officials said, includes protective military gear like body armor and night-vision goggles, as well as communications equipment — but not weapons. It comes on top of food rations and medicine announced by Mr. Kerry last February. While the State Department will determine the size of the package, an official said it could be double the $60 million in nonlethal aid already committed.

But Mr. Kerry’s expected announcement, officials said, may not come until after the United States secures a commitment from the Syrian opposition and its supporters that any government that replaces Mr. Assad’s would be inclusive, would protect the rights of his Alawite minority and other sects, and would abide by the rule of law.

Speaking to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Thursday, Mr. Kerry said his goal was “to get everybody on the same page with respect to what post-Assad might look like — commitment to diversity, pluralism, democracy, inclusivity, protection of minority rights.”

In addition, Mr. Kerry said, the United States wanted the opposition to be “open to the negotiating process to a political settlement” and to “abide by rules with respect to conduct in warfare.”

While the United States and European nations have insisted on democratic principles, American officials have been concerned that some of the opposition’s financial backers in Persian Gulf states have been less particular about the rebel factions they aid.

Among those that Mr. Kerry said he wanted to put “on the same page” are the “Qataris, Saudis, Emirates, Turks,” as well as the Europeans. Nurturing a unified, moderate opposition has been complicated by regional rivalries, with countries pushing their own favorites.

Not everyone in the Obama administration has necessarily been on the same page on policy toward the Syrian resistance. And State Department officials hope that the Istanbul meeting will enable the American side to close ranks as well.

In testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee on Wednesday, Gen. Martin E. Dempsey, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, voiced concern about the growing role of extremists among the anti-Assad fighters in Syria, and said identifying moderate members of the Syrian resistance had become more difficult.

“It’s actually more confusing on the opposition side today than it was six months ago,” General Dempsey said.

During his Senate testimony on Thursday, Mr. Kerry, when asked about General Dempsey’s comments, said one purpose of the Istanbul meeting was to identify and reinforce the moderate opposition.

1 2 NEXT PAGE »

Reporting was contributed by Alan Cowell from London; Hwaida Saad and Anne Barnard from Beirut, Lebanon; and Rick Gladstone from New York.

-

Turkey’s Camps Can’t Expand Fast Enough for All the New Syrian Refugees

The horrific statistical realities of the two-year conflict

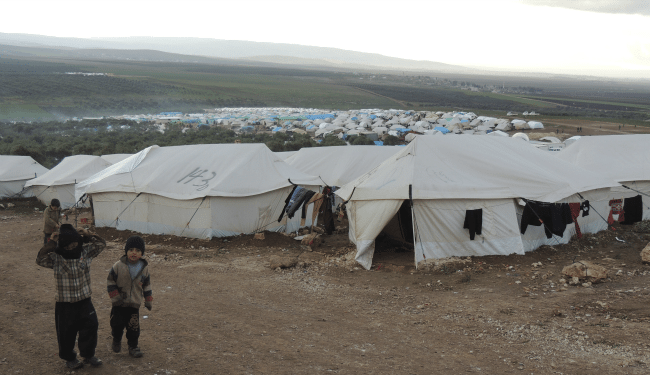

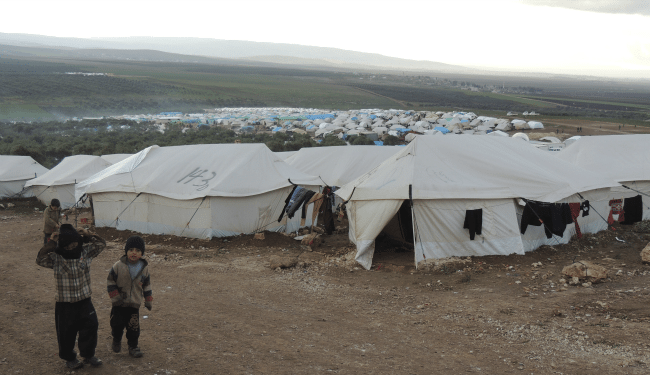

ARMIN ROSEN Syrian refugees in a refugee camp on the Syrian side of the border with Turkey, near Idlib, on January 29, 2013. (Reuters)

Syrian refugees in a refugee camp on the Syrian side of the border with Turkey, near Idlib, on January 29, 2013. (Reuters)The Syrian conflict escalated far faster than any of the world’s decision-makers anticipated. In January, a pledge conference in Kuwait raised $1.5 billion in humanitarian funding commitments for the conflict’s next six months, with the assumption that the war’s one millionth refugee wouldn’t be created until the middle of 2013. That grim threshold was cleared in March, which turned out to be the two-year-old conflict’s deadliest month .

With such little cause for optimism in an increasingly violent and multi-faceted conflict, the backlog of refugees on the Syrian side of the Turkish border seems like a portent of bigger problems to come.

Just six weeks later, there are 1.3 million Syrian refugees, although the international community seems to be adjusting its estimates to account for a situation that has slipped beyond any one actor’s control — and that likely wouldn’t be resolved even with president Bashar al-Assad’s ouster. In late March, Antonio Guterres, the UN’s High Commissioner for Refugees, told a Congressional hearing that there might be as many as four million Syrian refugees by the end of 2013. In March, the UN estimated that there were 3.6 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Syria; the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs is likely to revise that number upwards — perhaps as high as 4.5 million — in the coming weeks.

But the conflict’s severity doesn’t necessarily translate into greater political will, and it’s becoming apparent that the conflict has accelerated beyond the international community’s current ability to address it. “We are sleepwalking into a major disaster,” said Kristalina Georgieva, the European Union’s Commissioner for Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection. “The capacity to cope is outstripped by the intensified fighting … even if we all deliver on our pledges, it is now reaching the point where handling [the conflict] goes above and beyond humanitarian budgets.”

Simply, refugees are being created faster than even the best equipped of Syria’s neighbors can accommodate them. The starkest example of this is along the Turkish-Syrian border, where 100,000 people are estimated to be living between the conflict’s northern front lines and Turkish territory — partly because Turkey can’t expand its humanitarian capacity at the rate that refugees are arriving at the country’s doorstep. “The border remains fully open,” says Georgieva. “But it is not as freely possible to cross into Turkey as it was in the first months, or even the first year, of the conflict.” There are currently nine sizable (i.e., in the 15,000 inhabitant range) IDP camps on the Syrian side of the border. But by all accounts, the amount of aid reaching IDPs is less than what is available at official, UN-apportioned camps in neighboring countries — working across the border can be politically sensitive, as well as dangerous, for some governments and relief organizations. In total, the international community’s humanitarian safety net covers about 2 million people out of a total IDP and refugee population of nearly 5 million.

Turkey isn’t turning away refugees, which would represent a violation of standard humanitarian practice and perhaps even international law. But the country is currently in the process of building six new refugee camps, on top of the 17 that already exist. “Turkey for security reasons and absorption capacity reasons is now being more selective, prioritizing crossing for those who are at highest need,” says Georgieva, categories which include women, children, and the wounded.

Still, it’s notable that Turkey, which is both more developed and politically stable than Lebanon and Jordan, is facing these kinds of challenges with refugee absorption. “The Turkish border has at times seen numbers so overwhelming that they’ve had to slow down the flow in terms of accepting those crossing at the time,” says Kelly Clements, a Deputy Assistant Secretary at the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. She says that at least some of the IDPs along the border don’t want to enter Turkey at the moment. “They’re in a place where they can seek and obtain assistance more easily than in some of the more heavily bombarded and conflict-ridden communities,” she says. “So they’ve moved closer to the border. But not all of them have actually wanted to cross.” Overall, she says, “Turkey’s been managing exceptionally well.”

Even so, the full ramifications of a massive and perhaps semi-permanent population displacement in the heart of the Middle East might not be known for decades. For now, the numbers are jarring and suggest a resettlement of potentially historic proportions — for instance, the 440,000 refugees in Jordan represents about 6.5 percent of the already-fragile country’s population. The strain on neighboring states is an immediate, political problem with clear humanitarian consequences. The borders with Jordan and Turkey remain open. But it might not remain that way. “Jordan is now very close to saying, we cannot cope anymore, close down the border, create a buffer zone inside Syria,” says Georgieva. “A buffer zone is not an impossibility, but who’s going to protect it?”

It’s not just that more funding is needed — although the pledges from the Kuwait conference are proving worryingly inadequate. The humanitarian situation also has a clear diplomatic element to it. It might get to the point where keeping borders open and protecting Syrian refugees means reaching some kind of multilateral political accommodation with Jordan and Turkey — something that addresses concerns over the social and economic strain of hosting a large and perhaps long-term refugee population.

Humanitarian-related tensions between the international community and Syria’s neighbors might lie another couple million refugees in the future. But if the past year has proven anything, it’s that such moments could come sooner than world leaders want or expect them to. With such little cause for optimism in an increasingly violent and multi-faceted conflict, it’s possible to see the backlog of refugees on the Syrian side of the Turkish border as a portent of bigger problems to come. At least for Clements, it’s difficult to overstate the anxiety of the present moment. “We’re already at worse case scenario,” says Clements. “We’re there.”

-

Turkey plans refugee camp for Syrian Christians, Ecumenical News

Syrian refugees are seen in a refugee camp on the Syrian side of the border with Turkey, near Idlib January 29, 2013, in this picture provided by Shaam News Network. Picture taken Jan. 29, 2013. ReutersPHOTO: REUTERS / MUHAMMAD NAJDET QADOUR / SHAAM NEWS NETWORK / HANDOUT

The Turkish government is setting up a refugee space specifically for displaced Christians, two years after the civil war in Syria began.

Not all Christians are, however, welcoming the move.

The Turkish Disaster and Emergency Management (or AFAD) announced it will separate Christians into their own camp near Mor Abraham Syriac Monastery by the town of Midyat.

The area is located about 30 miles (50 kilometers) from the Syrian border.

“A month ago, some churches met with the Turkish foreign minister, and they requested that for Christians it would be better to open another camp,” Metin Corabatir, a spokesman for the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Turkey said Tuesday.

Corabatir said the camp is likely the response to a series of meetings between Turkish officials and churches in the area.

The plight of Syrian Christians has become increasingly glaring in recent months.

Christians make up about 10 percent of the 22 million people in Syria.

In March, the U.S. Bishops’ Catholic Relief Services reported that about 200 Syrian Christians were seeking shelter in local Turkish churches, out of fear of intolerance at the 17 relief camps near the border.

The Turkish disaster agency estimates that there are about 200,000 refugees near the area in dispute, most of whom are predominantly Sunni Muslim.

Some Christian leaders are, however, not welcoming the separation of Christians from other Syrians.

Father Francois Yakan, the patriarchal vicar of the Chaldean Catholic Church in Turkey, was quoted by the Catholic Herald in the UK as saying that while he was unaware of any such plans that they would not be good.

The Catholic leader worries that such a move would segregate Christians in the area.

“These are people who have been living together for centuries. To be separating them now is not a good idea,” Yakan said.

Reuters news agency reported that the Turkish government strongly denied a sectarian or ethnic agenda.

A Turkish foreign ministry official said the two tented camps, to be completed in less than a month, are being built in Midyat, a town in southeastern Mardin province some 50 km (30 miles) from the Syrian border.

The U.N. estimates that up to 70,000 people have been killed in the Syrian Civil War and the carnage has displaced 1 million refugees between Turkey, Jordan, Iraq, Egypt and Lebanon.

Half of those refugees, the U.N. estimates, are currently residing in Turkey.

via Turkey plans refugee camp for Syrian Christians, Ecumenical News.