By Roy Gutman — McClatchy Newspapers

ISTANBUL, TURKEY — In a move intended to trim support to Islamist extremists who now play a leading role in the Syrian uprising, the United States, Turkey and key Gulf allies this weekend agreed to funnel future military aid only through the internationally recognized Syrian rebel coalition.

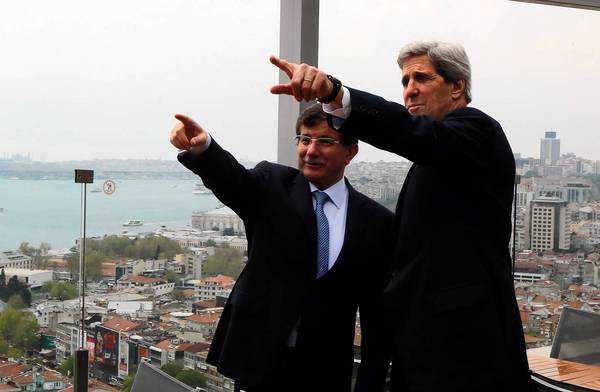

It’s one of a set of steps that Secretary of State John Kerry and other western and Mideast officials announced early Sunday, in what appears to be a concerted new drive to end the two-year-long civil war that pits the Syrian government of President Bashar Assad, who enjoys support from Russia and Iran, against a diverse group of rebels backed by the United States, Turkey, and European allies along with Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

Among the steps by the “Friends of the People of Syria” were a U.S. decision to provide another $123 million in non-lethal aid to the Syrian rebel fighters, doubling the aid to date, and a call by all 11 participants for a negotiated solution to bring in a new transitional government.

They also condemned Assad’s use of ballistic missiles and endorsed a written pledge by the Syrian opposition to hold individuals responsible for war crimes and not to seek “revenge and retribution” against members of Assad’s Alawite sect or any other minority.

All 11 countries at the Istanbul meeting “made a commitment to direct their military aid and assistance directly and uniquely, solely, through the Supreme Military Command,” headed by Gen. Salim Idriss, a former Syrian army general who defected last July, Kerry told reporters Sunday. “This may be one of the most important single things that was agreed to…that can make a difference to the situation on the ground.”

How to provide aid to the rebels without empowering militant Islamist extremists who have been at the forefront of anti-Assad victories for the past year has bedeviled countries seeking an end to the Assad regime. The Supreme Military Command is poorly organized and its control of fighters on the ground is uncertain. Aid from Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, the primary providers of military aid, have dealt primarily with individual commanders on the ground, many of whom are affiliated with Islamist extremist movements.

Idriss made a lengthy presentation at the meeting of foreign ministers Saturday evening, giving a rundown of the military situation, province by province, and describing in detail the forces that report to him. He assured the ministers that he would provide a full account of “everything you provide to me,” according to a diplomat who attended.

Kerry told reporters everyone was impressed by the “strength and clarity” of the Idriss presentation and said the Syrian general “could not have been more clear about his determination to separate what he and the opposition are doing from what some of the radical and extreme elements are doing.”

“I think we are quite confident that he is a strong leader with a capacity to make a difference,” Kerry said.

Military analysts who closely follow the war say that Gulf states, and individual donors, have been backing the Nusra Front, which the U.S. government has labeled a terrorist group identical to al Qaida in Iraq, and similar groups because of their effectiveness. More moderate rebel groups have said they’ve been starved for support. A senior State Department official, briefing reporters Saturday, said a provincial military commander with thousands under his command, said recently that he had to rely on donations obtained by his troops from family and friends, because Idriss was unable to deliver.

“Your help to Salim Idriss isn’t going fast enough,” the official quoted the commander as saying. “How do I tell my guys, ‘Wait for the stuff from Salim Idriss. Don’t take that money from that business guy who is backed by an Islamist network’?” The senior official spoke anonymously because he said he was not authorized to speak on the record.

The main diplomatic move announced Sunday was the call for a return to discussions with Russia on a political resolution of the conflict, based on an accord agreed reached in Geneva last July that called for a transitional government, members of whom would be nominated by, and accepted by both sides.

Assad named an aide to represent him in the talks, but the rebels did not, and diplomats say Russia has insisted that Assad effectively have a major role in the transition. In the joint statement early Sunday, the 11 participants – Egypt, France, Germany, Jordan, Italy, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Britain, the United States and Turkey, said “Assad and his close associates have no place in the future of Syria” and should cede power to a transitional executive body.

Kerry sought to offer at least a rhetorical olive branch to Russia, noting that the “framework of peace” was agreed to “by the international community, including our friends, the Russians.” But the joint statement of the 11 countries also warned that if Assad rejects a peaceful transition, “further announcements regarding expanding our assistance will follow.”

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, who negotiated the framework with Kerry’s predecessor, Hillary Clinton, was in Turkey on the eve of the 11-nation talks, but there was no sign of any political shift. The discussion is expected to continue Tuesday, when Kerry attends a meeting of NATO foreign ministers that Lavrov is also expected to attend.

Email: [email protected]; Twitter: @RoyGutmanMcC

via ISTANBUL, Turkey: U.S., allies agree on rules for sending military aid to Syrian rebels | World | ADN.com.