According to a recent report, former NATO Secretary-General George Robertson confirmed that Turkey possesses 40-90 “Made in America” nuclear weapons at the Incirlik military base.(en.trend.az/)

Does this mean that Turkey is a nuclear power?

“Far from making Europe safer, and far from producing a less nuclear dependent Europe, [the policy] may well end up bringing more nuclear weapons into the European continent, and frustrating some of the attempts that are being made to get multilateral nuclear disarmament,” (Former NATO Secretary-General George Robertson quoted in Global Security, February 10, 2010)

“‘Is Italy capable of delivering a thermonuclear strike?…

Could the Belgians and the Dutch drop hydrogen bombs on enemy targets?…

Germany’s air force couldn’t possibly be training to deliver bombs 13 times more powerful than the one that destroyed Hiroshima, could it?…

Nuclear bombs are stored on air-force bases in Italy, Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands — and planes from each of those countries are capable of delivering them.” (“What to Do About Europe’s Secret Nukes.”Time Magazine, December 2, 2009)

The “Official” Nuclear Weapons States

Five countries, the US, UK, France, China and Russia are considered to be “nuclear weapons states” (NWS), “an internationally recognized status conferred by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)”. Three other “Non NPT countries” (i.e. non-signatory states of the NPT) including India, Pakistan and North Korea, have recognized possessing nuclear weapons.

Israel: “Undeclared Nuclear State”

Israel is identified as an “undeclared nuclear state”. It produces and deploys nuclear warheads directed against military and civilian targets in the Middle East including Tehran.

Iran

There has been much hype, supported by scanty evidence, that Iran might at some future date become a nuclear weapons state. And, therefore, a pre-emptive defensive nuclear attack on Iran to annihilate its non-existent nuclear weapons program should be seriously contemplated “to make the World a safer place”. The mainstream media abounds with makeshift opinion on the Iran nuclear threat.

But what about the five European “undeclared nuclear states” including Belgium, Germany, Turkey, the Netherlands and Italy. Do they constitute a threat?

Belgium, Germany, The Netherlands, Italy and Turkey: ”Undeclared Nuclear Weapons States”

While Iran’s nuclear weapons capabilities are unconfirmed, the nuclear weapons capabilities of these five countries including delivery procedures are formally acknowledged.

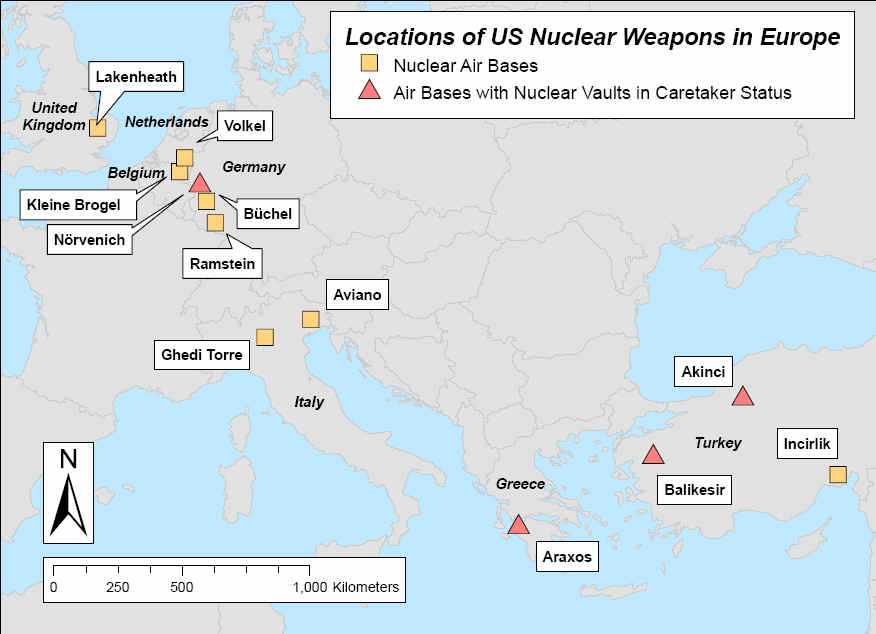

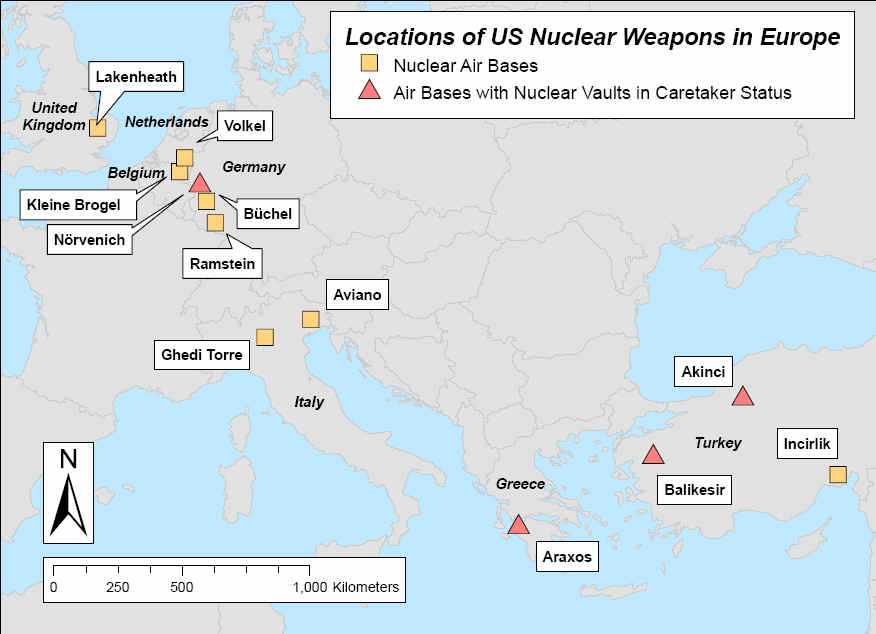

The US has supplied some 480 B61 thermonuclear bombs to five so-called “non-nuclear states”, including Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Turkey. Casually disregarded by the Vienna based UN Nuclear Watchdog (IAEA), the US has actively contributed to the proliferation of nuclear weapons in Western Europe.

As part of this European stockpiling, Turkey, which is a partner of the US-led coalition against Iran along with Israel, possesses some 90 thermonuclear B61 bunker buster bombs at the Incirlik nuclear air base. (National Resources Defense Council, Nuclear Weapons in Europe , February 2005)

By the recognised definition, these five countries are “undeclared nuclear weapons states”.

The stockpiling and deployment of tactical B61 in these five “non-nuclear states” are intended for targets in the Middle East. Moreover, in accordance with “NATO strike plans”, these thermonuclear B61 bunker buster bombs (stockpiled by the “non-nuclear States”) could be launched “against targets in Russia or countries in the Middle East such as Syria and Iran” ( quoted in National Resources Defense Council, Nuclear Weapons in Europe , February 2005)

Does this mean that Iran or Russia, which are potential targets of a nuclear attack originating from one or other of these five so-called non-nuclear states should contemplate defensive preemptive nuclear attacks against Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and Turkey? The answer is no, by any stretch of the imagination.

While these “undeclared nuclear states” casually accuse Tehran of developing nuclear weapons, without documentary evidence, they themselves have capabilities of delivering nuclear warheads, which are targeted at Iran. To say that this is a clear case of “double standards” by the IAEA and the “international community” is a understatement.

Those estimates were based on private and public statements by a number of government sources and assumptions about the weapon storage capacity at each base

The stockpiled weapons are B61 thermonuclear bombs. All the weapons are gravity bombs of the B61-3, -4, and -10 types.2 .

.(National Resources Defense Council, Nuclear Weapons in Europe , February 2005)

Germany: Nuclear Weapons Producer

Among the five “undeclared nuclear states”, “Germany remains the most heavily nuclearized country with three nuclear bases (two of which are fully operational) and may store as many as 150 [B61 bunker buster ] bombs” (Ibid). In accordance with “NATO strike plans” (mentioned above) these tactical nuclear weapons are also targeted at the Middle East.

While Germany is not categorized officially as a nuclear power, it produces nuclear warheads for the French Navy. It stockpiles nuclear warheads (made in America) and it has the capabilities of delivering nuclear weapons. Moreover, The European Aeronautic Defense and Space Company – EADS , a Franco-German-Spanish joint venture, controlled by Deutsche Aerospace and the powerful Daimler Group is Europe’s second largest military producer, supplying .France’s M51 nuclear missile.

Germany imports and deploys nuclear weapons from the US. It also produces nuclear warheads which are exported to France. Yet it is classified as a non-nuclear state.

TEHRAN (FNA)- Tel Aviv’s recent apology to Ankara is a US game to undermine the anti-Israel resistance movement in the region, a senior Iranian commander said on Saturday.

TEHRAN (FNA)- Tel Aviv’s recent apology to Ankara is a US game to undermine the anti-Israel resistance movement in the region, a senior Iranian commander said on Saturday.