By Mehmet Efe Biresselioglu*

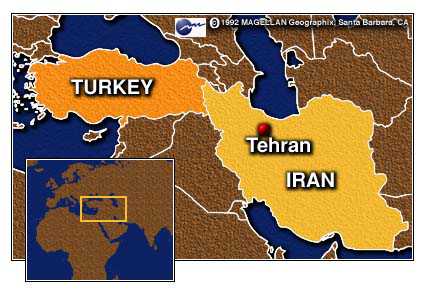

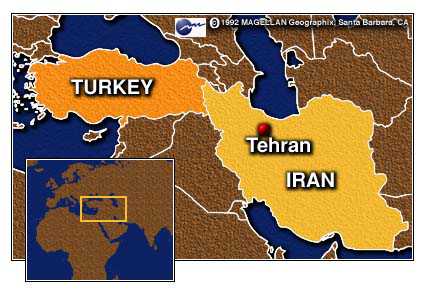

The relationship between Turkey and Iran has undergone considerable change during the rule of Turkey’s Justice and Development Party (AKP). Starting with Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s visit to Tehran on 28 and 29 July of 2004, there has been a thawing of relations between the two neighbors. This visit was a key sign of the winds of change affecting Turkey’s world view. From that time, both Turkey and Iran began to adopt the view that they should put aside deep-rooted and enduring ideological differences, and instead to increase trade, while also addressing the continuing problem of terrorism.

Changes in Turkey’s World View

The pace of change in Turkish foreign policy rhetoric has progressively escalated during the rule of the AKP government. The architect of this change is Ahmet Davutoğlu, who was appointed chief advisor to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in 2002, and thereafter nominated as Turkish Foreign Minister in 2009.

Turkey has been able to formulate a systematic and unified methodological approach to its foreign policy in the 21st century. According to Davutoğlu, Turkey now adheres to three main principles in its foreign policy making. These three main principles are:

- a ‘visionary’ rather than ‘crisis-oriented’ approach;

- a universal applied foreign policy based on a consistent and systematic framework;

- the adoption of a new discourse and diplomatic style, which has resulted in the spread of Turkish soft power in the region.

Moreover, Davutoğlu has proposed five operational principles that help to enforce these main principles of Turkish foreign policy. These are:

- striking a balance between security and democracy;

- zero problems with neighboring states;

- a proactive and pre-emptive approach to ‘peace diplomacy;’

- a multi-dimensional foreign policy;

- a ‘rhythmic’ diplomacy.

These principles are clearly visible in recent international events involving Turkey. Turkey’s policy towards Lebanon, Turkey’s role as a mediator between Syria and Israel, and the new Turkish position on the Israel/Palestine conflict have all demonstrated Turkey’s renewed Middle East foreign policy. Moreover, Turkey’s constructive approach to Iran’s nuclear issue with Brazil in the UN, and its wider role as go-between for Iran and the Western world, has enhanced and extended the new approach of Turkish foreign policy.

The Historical Relationship between Turkey and Iran

Bilateral relations between Turkey and Iran have been subject to the influence of various political factors, especially on the Turkish side. These tendencies derive from the realities of having a common border, and common cultural and other factors that are many centuries old. In addition, there is a 500-year history of peaceful relations, extending back to the time of the Ottoman and Persian Empires.

Following the military coup d’état in 1980 in Turkey and the Islamic Revolution of 1979 in Iran, anti-Iranian propaganda increased in Turkey because of the threat to Turkey’s secular ideology, and of the export of the revolution to Turkey. However, the threat was completely unreal; as Turkey’s secular tradition would not allow this outcome.

Until recently, bilateral relations had been negatively affected over several decades by various issues. These included the suspicion from both sides that the other country was supporting Kurdish terrorist groups in its country, i.e. PKK in Turkey and the MKO in Iran, interaction between Turkey and the United States and Israel, rivalries in the Caucasus regarding energy transit. These and other forms of negative propaganda against Iran have had adverse effects on bilateral relations until recent years.

Economic Issues

Today, the volume of trade between Iran and Turkey stands at about $13 billion. Economic officials from both countries expect this figure to rise to $20 billion per year over the following five years.

Moreover, the Turkish government has agreed that Turkish businessmen should be allowed to export up to $100 million worth of goods to Iran on a zero tariff basis. In addition to that, Iran’s Mellat Bank announced its readiness to financially support necessary measures to encourage cross-border import/export. Ankara and Tehran have already initiated talks about cooperation in different sectors, and to solve the customs tariff problems.

Oil and natural gas are the major goods in the trade relations between Turkey and Iran. Turkey hopes to enhance its energy security by reducing its dependency on Russian oil and natural gas, by including Iranian oil and natural gas in its energy composition. The already completed Tabriz-Erzurum pipeline has a capacity of 14 bcm of gas per year, though currently only one quarter of its capacity is being used; however, in general this development allows for considerably increasing of natural gas imports from Iran to Turkey. The two countries have signed an agreement for Turkish and Iranian companies to cooperate on exporting gas to Turkey, with the option for subsequent resale. Also, Turkey has been granted the right to explore and extract natural gas from Iran’s significant South Pars field.

Current Dynamics in Turkish-Iranian Relations and Israel’s Role

Turkey has strengthened its ties with Iran since the AKP took power in 2002. As a result of Turkey’s policy goals of becoming a regional power and achieving a ‘zero problems with neighbors’ foreign policy, Turkey has offered to become a mediator in disputes between Iran and the Western world, and also between Iran and Israel. The main concern in this respect has been Iran’s nuclear program.

However, the recent ‘Mavi Marmara’ incident has jeopardized not only Turkish-Israel relations, but relations between Turkey and the West. Eight Turks and one US citizen of Turkish decent were killed by Israeli forces as the ship, in spite of discouragement from Ankara, tried to reach Gaza. This incident has had serious repercussions in the Middle East, and Turkey has started to be seen as the leading voice of the Muslims, including Arabs.

On the other hand, Turkey has been criticized by the West and domestic opposition as ‘turning east,’ ‘joining an Islamist bloc’ or ‘turning its back on the West.’ However, Turkey’s aim is to be an active regional power actor not only through hard power, but to use its soft-power capacity by increasing economic engagements, supporting this with trade and investment, but also increasing its social and popular connections in the region.

Still, Turkey is also increasing its level of relationship with Iran by supporting its nuclear program, but only for peaceful purposes. There are two views on Iran’s nuclear program, first that Iran has plans to threaten Israel and the US with nuclear weapons, and second that Iran genuinely needs nuclear energy, as it is unable to refine enough of its petroleum products, and therefore needs alternative sources to exchange in order to supply its energy needs. This is a result of US sanctions, leaving Iran’s energy sector needing more than $100 billion dollars of investment in the coming decade.

Turkey is supporting Iran’s second, peaceful aim and for that reason is trying to mediate between Iran and the West, accepting Iran’s guarantee that it will not build nuclear weapons.

Hence as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council, Turkey voted ‘no’ against additional sanctions on 9 June. It should not be considered that Turkey’s “no” was in support of any Iranian nuclear military ambitions. Rather, it argued that Turkey, along with Brazil, was convinced that it has US support to negotiate the exchange of a substantial amount of Iran’s low-enriched uranium stockpile, as set out in the 17 May Tehran Agreement. The Turkish aim was thus to protect its bargaining power, and moreover to adhere to the Tehran Agreement.

The Real Concern

A real concern, however, remains that even with 1.2 tons of low-enriched uranium exported to Turkey for storage, Iran will still retain enough to build a nuclear warhead. Therefore, Iran needs to demonstrate to the world its good will and also to explain why it needs nuclear power instead of confronting the West. Turkey and the West want to eliminate any possibility of nuclear proliferation in the Middle East, and Iran’s nuclear program is the most urgent nuclear proliferation test facing the world at the present time.

Turkey’s aim is to promote an advanced diplomatic solution instead of a disagreement between the West and Iran, and Turkey’s changing foreign policy would allow this, with its increasingly active role in the Middle East, compared to its past approaches. Despite Turkey’s deepening relations with Iran, the AKP government still does not support Iran’s potential nuclear military aims. Rather, these efforts are perceived by Turkey as solely to promote regional stability.

……………………

Balkanalysis.com’s Turkey editor Mehmet Efe Biresselioğlu is an Assistant Professor at Izmir University of Economics’ International Relations and EU department and a board member of the Turkish Energy and Climate Change Foundation (ENIVA). His research interests include geopolitics, energy security and sustainable energy, geostrategic issues with a geographic focus on Turkey, Russia, the Greater Caspian area, the Middle East and also with Turkey’s relations with the EU and US.

“Turkey has very good credibility and connectivity to the West but also the ability to reach out to Tehran and speak to the Muslim world with clarity and perspective that we could gain from,” he told Today’s Zaman in an exclusive interview.

“Turkey has very good credibility and connectivity to the West but also the ability to reach out to Tehran and speak to the Muslim world with clarity and perspective that we could gain from,” he told Today’s Zaman in an exclusive interview.