Turkey Facilitates Talks with Iran, Following Bickering over Venues

Ankara’s involvement in the Iranian nuclear issue has been one of the most troublesome items in its foreign policy agenda complicating not only its relations with Tehran but also the West. As the US sought to mobilize a broad-based coalition to stop Iran’s nuclear enrichment activities, on the grounds that it might have military objectives, Turkey stood against coercive approaches and argued for the utilization of diplomatic channels to address this issue. When the US pushed for a new round of sanctions in 2010, Turkey again raised similar objections and, in a joint initiative with Brazil, brokered a swap deal, resulting in the Tehran Declaration of 2010 (EDM, June 1, 2010).

Though Turkey also vetoed the UN Security Council resolution authorizing sanctions, it eventually agreed to implement them, noting that they reflect the will of the international community. Turkey, however, underlined that it would not abide by the unilateral sanctions introduced by the US and its European allies.

While the United States has continued to implement the sanctions to increase gradually pressure on Tehran, attempts to restart the dialogue between the two sides have been underway. Both parties expressed appreciation for Turkey’s readiness to facilitate this dialogue, which led to the talks held in January 2011 in Istanbul (EDM, January 25, 2011). The talks failed to produce any significant outcome. The efforts to resume the talks have been stalled, with Western powers asking Iran to come to the table with concrete proposals.

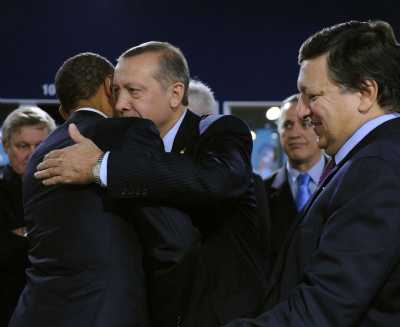

Turkey continued to offer its mediation services in the middle of other diplomatic initiatives it has undertaken. These other Turkish initiatives include reaching out to Tehran and the West in regards to the Syrian crisis, and the situation in Iraq. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s meeting with US President Barack Obama in Seoul on the occasion of the nuclear summit and his subsequent visit to Tehran enabled first-hand discussions with both parties. Again, while Ankara strongly reiterated its commitment to Iran’s right to develop and use peaceful nuclear technology, it also underlined that all military activities should be under international inspection (Anadolu Ajansi, April 5).

Expectations were raised that Turkey’s go-between role might be paying off and negotiations could soon be held in Istanbul on April 13-14. However, the controversial statements coming from some high-ranking Iranian officials clouded the air. Despite Iranian Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Salihi’s depiction of a meeting in Istanbul as the best alternative, other officials called for holding the meeting in “friendly” countries such as Syria, Iraq or Lebanon. They criticized Turkey’s pro-Western policy in Syria and other regional problems, questioning Ankara’s neutrality (www.dunyabulteni.com, April 3).

Having invested diplomatic credibility in this initiative, such statements were shocking for Turkish leaders. Erdogan reacted harshly, calling Iranian officials to act sincerely (Zaman, April 6). The escalating tensions could only be mitigated with direct communication between foreign ministers, and finally the Iranian side confirmed the meeting in Istanbul (www.presstv.ir, April 8).

These verbal exchanges and Erdogan’s questioning of Iranian sincerity underscored the transformation of the bilateral relationship and Turkey’s involvement in the Iranian nuclear dispute since 2010. First, Turkey’s approach to the talks has changed. While in 2010 Turkey was actively mediating on the issue, it has retreated from that position. Already in the January 2011 meeting, Turkey underlined that it seeks to facilitate the talks, by providing a venue. However, at that time, Turkey still believed the Tehran Declaration provided a constructive framework to discuss further diplomatic initiatives, and emphasized readiness to assist the parties if they decided to address the issue along the lines contained in that declaration. Since then, however, Turkey seems to also have backtracked from that position as well, and the content of the talks have yet to be set by the parties.

Moreover, Turkey’s relationship to both sides has been transformed to a great extent. Compared to 2010, while Turkey now enjoys more cooperative relations with the US, Ankara’s ties to Tehran have been severed over other developments in the intervening period. In 2010, Turkey was seen as largely uncritical of Tehran’s position, which even led to charges that it was pro-Iranian or providing shelter for Tehran. By the January 2011 meeting, the change in Ankara’s position was well underway. Turkey increasingly called on Iran to be more transparent and reassure the international community that its nuclear program had peaceful purposes. Turkey also moved in the direction of seeking a greater degree of protection against potential threats that might be posed by the Iranian nuclear program. Especially, Turkey’s decision to support NATO’s missile shield program and its agreement with the US for the installation of early warning radars on its soil in late 2011 were important indicators of this transformation.

The changes in Turkey’s policy seem to have altered Tehran’s perceptions, which no longer views Ankara as a “neutral” actor. This was perhaps partly the reason why Iranian officials raised vocal objections to Istanbul as the venue for the talks. However, Iran is being negatively affected by the sanctions, which must have forced it to adopt a more conciliatory position to avoid completely losing Turkey in this dispute, hence Teheran’s agreement to hold talks in Istanbul.

As the talks are fast approaching, there are conflicting signals about the prospects of achieving some progress. Earlier, Western officials underlined that in the talks they would seek to get Iran to suspend high-level enrichment and close down an underground nuclear facility near Qom. The Iranian officials rebuffed immediately any preconditions (www.presstv.ir, April 9). The head of Iran’s Supreme National Council, Saeed Jalili, stated that they would come to the table with a constructive approach and propose new initiatives (www.presstv.ir, April 11). Given Iran’s earlier track record, it remains to be seen if this is a sincere constructive approach or yet another delaying tactic. But in any case, it will be up to the parties to reach a common ground, not Turkey, whose sole involvement now is to facilitate this dialogue.