Shortened version of article “Revisiting the Fire of Izmir” published in Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, V. 41, No. 1, Fall 2017.

September 13, 2012 is the 90th anniversary of the “Inferno of Izmir” when a great fire broke out that destroyed more than three-fifths of the town. Some Western sources have wrongly placed the culpability for the fire on Turks that recaptured the city from occupying Greek army in September 1922. To that end, Governor George Pataki of New York, playing ethnic politics, shamelessly issued a proclamation in 2002 blaming Turks for the fire.

Historical testimonials, however, clearly indicate that, while the retreating Greek army had a role in starting the fire, Armenian terrorists, dressed in Turkish uniforms, did the biggest damage.

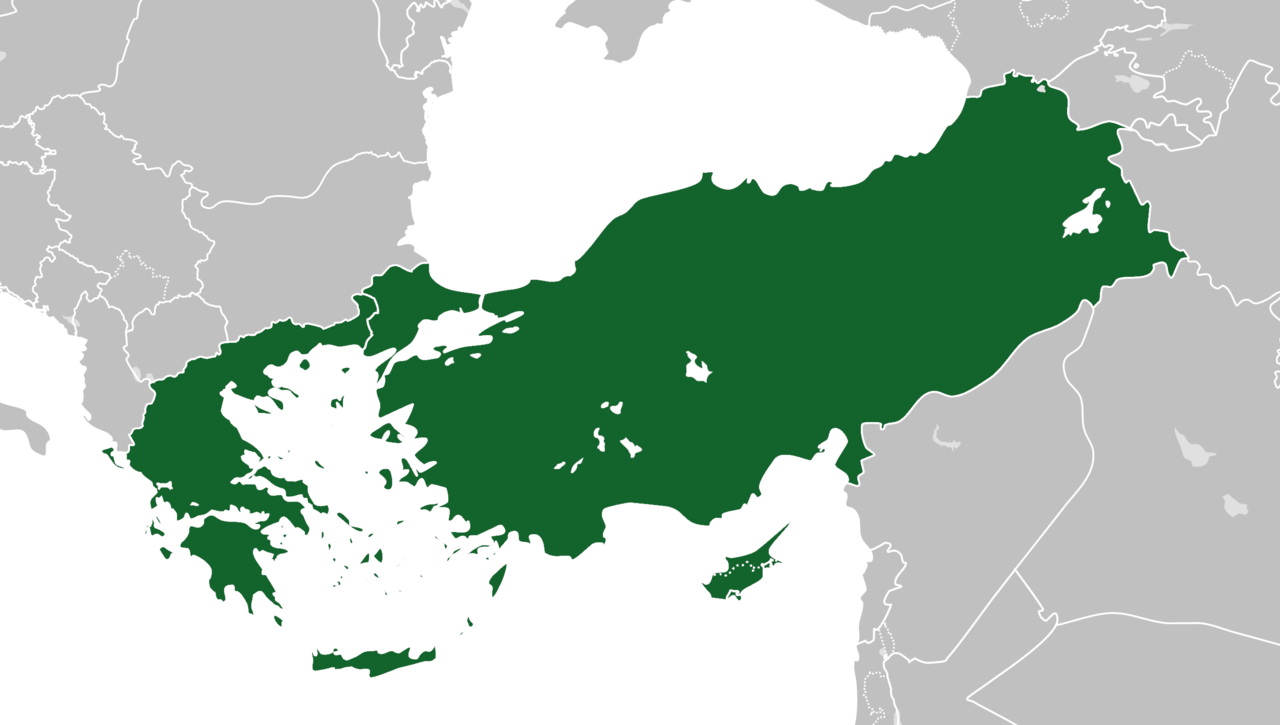

Atrocities by Greek and Armenian elements had actually started as early as mid-May 1919 right after the Greek landing in Izmir. Due to the pressure of the Entente’s representatives, the Greek High Command sentenced dozens of criminals in spring 1919; among the sentenced were 12 Armenians. The atrocities continued during the whole Greco-Turkish war, with Armenians participating in the violence and destruction. In a July 1922 report, Elzéar Guiffray, the administrator of the Izmir’s port, estimated that more than 150,000 Turks were killed, or “disappeared,” as a result of the Greek armed forces’ war crimes.

The summer of 1922 was a culmination of the Greek scorched-earth policy. The Greek army forced the Christian population to leave, and burned everything, including houses of the Christians. This scorched-earth policy is established both by the report of Father Ludovic Marseille, chief of the Catholic mission in Eskișehir (who said that the Greeks had lost forever any right to speak about “Turkish barbarity”), and by a dispatch sent by the staff of USS Litchfield to Admiral Mark Bristol, the US High Commissionner at the American Embassy in Istanbul.

According to a report by a the French Navy’s Intelligence Service (Izmir office), dated 15 November 1920, Armenians, both civilians and legionnaires, arrived in Izmir from Cilicia, engaged in arson, and tried to excite the Greek army against the Turkish population. (During the French occupation of Cilicia, the Armenian Legion committed so many crimes that the Legion itself was disbanded in disgrace [phrase used by French General Jules Hamelin in his mémoires] in summer 1920 and at least five Armenians and one Assyrian were hanged by the French military justice in July 1920 alone. The practice of arson by Armenians, especially in Adana, was a recurrent grievance in the French sources). Missionary Alexander MacLachlan, based on his investigation, also concluded that “Armenian terrorists, dressed in Turkish uniforms, set fire to the city.” The terrorists were evidently attempting to bring Western intervention.

The Western sources clearly demonstrate that the attitude of the Turkish army during the final offensive was strikingly correct. For instance, General Pellé, the French High Commissioner in Istanbul, wrote on September 8, 1922, that since a long time, even the Greek patriarchate had not reported to him any “Kemalist massacre.”

After a careful investigation made together with Admiral Charles Dumesnil, chief of the French Navy in the Near East, and other French representatives, French Consul General Michel Graillet of Izmir also concluded that “the Turkish army has clearly nothing to do with the arson,” and that “quite the contrary, it fought the fire to the extent of its meager resources.” Dumesnil knew the Turkish army from the Çanakkale battle where he had fought. If the irregulars (“çete”) of the Turkish army pillaged a house, they faced immediate execution.

The Turkish army, in fact, had no reason to start fire in Izmir. The fleeing Greek army had abandoned huge quantities of military and food supplies that were desperately needed by the Turkish army and civilians. During several weeks after the fire, Turkish commanders were contemptuous of suggestions, made in a few quarters, that they had any responsibility for the burning. The commanders said that, considering what the Greeks had left behind, it would have been foolish of them to set fire to the city.

In short, the “Inferno of Izmir” on September 13, 1922 was mainly committed by Armenian terrorists, but also aided by Greek elements.

Maxime Gauin is a researcher and a Ph.D. candidate at the Department of History, Middle East Technical University.