History suggests British Jewish leaders are wrong to shy away from the notion of distinctive voting patterns among Jews

Geoffrey Alderman

Geoffrey Alderman

In the early 1970s, as I researched a textbook on the British electoral system, I became aware of a very significant gap in the then existing literature on voting habits among the British electorate. A great deal of material existed, naturally, on socio-economic class and its electoral impact. There was some material – not as much as there might have been – on the relationship between religion and voting. And some research had been carried out into the Irish vote – research that was principally an offshoot of the much greater body of research into “the Irish question”. But on the relationship between ethnicity and voting there was very little indeed. I was determined to repair this omission, and began polling Jewish voting intentions in selected London constituencies.

A phone call reached me from an organisation calling itself the Board of Deputies of British Jews. I was invited to lunch with its so-called defence department. And at that lunch I was ordered – repeat ordered – to cease forthwith my investigation of Jewish voting habits. Jews, I was told, voted just like everyone else. To poll a sample of Jews was to poll a sample of “ordinary” voters – no more and no less. So what was the point of my efforts? Besides, my hosts added, to ask how Jews were going to vote, or had voted, was to plant in the minds of the non-Jewish community, among whom we British Jews lived, the idea that Jews were not fully integrated into British society. I was told that Jews, in fact, were fully integrated. There was, therefore, no “Jewish dimension” to an election, and to suggest otherwise was to place the entirety of British Jewry in some (ill-defined) jeopardy.

I did not pay attention to these strictures. Or rather, I did pay attention to them, but only as evidence that could help me answer the question why the Jewish vote in British politics had been so poorly researched. Within British Jewry, image is everything. And the fact was that for generations, the fathers of the community had decreed that there must be no hint of a special, distinctive “Jewish” vote in the British body politic.

History, however, tells a different story. The votes of Jewish electors played a pivotal role in the epic struggle of Lionel de Rothschild (1847-58) to enter the House of Commons as a professing Jew, because the constituency for which he repeatedly stood – the City of London – contained several hundred Jewish businessmen who qualified for the property-related franchise. The parliamentary career of Samuel Montagu, a Yiddish speaking banker, was built on his relationship with his Jewish electors in that most Jewish of constituencies, Whitechapel, for which he sat as Liberal MP 1885-1900. The near-defeat of the Labour candidate at the Whitechapel by-election of November-December 1930 was a major factor in the decision of Ramsay Macdonald’s minority Labour government to ditch its anti-Zionist policy in Palestine.

The Jewish vote was pivotal to the 1945 victory of Britain’s last Communist MP, Phil Piratin, at Stepney, but it was equally pivotal to the defeat of Maurice Orbach (a self-proclaimed Labour Zionist who had conspicuously failed to support Israel during the Suez crisis) at East Willesden in 1959. In February 1974, his Jewish electors saved John Gorst, a gentile Zionist, from defeat at Hendon North. Four years later, on the other side of London, the Jews gave the Conservative candidate a resounding victory at a dramatic by-election at Ilford North, where Sir Keith Joseph had openly – and most successfully – campaigned for his Jewish brethren to support Thatcherite economic and immigration policies.

What of the present electoral contest? Jews, however defined, form no more than half of one percent of the UK population, but they are heavily concentrated in London and Manchester. Of the constituencies in which Jews account for at least 10% of the population, seven are Labour held. One of these – Finchley & Golders Green – is so highly marginal that it seems bound to be lost to the Conservatives irrespective of any special Jewish factor.

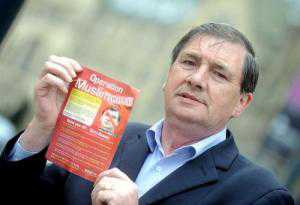

But in another, the adjacent Hendon seat, which could fall to the Tories on a swing of about 3.8%, there is an ongoing battle for the Jewish vote.Andrew Dismore, who has held the seat for Labour since 1997, has impeccable Zionist credentials (he would not otherwise have become MP for Hendon), but his constituency standing has been undermined by the Labour’s government’s failure to amend the “universal jurisdiction” law, which currently permits private citizens to apply for the arrest of prominent Israeli politicians who set foot on British soil, and by David Miliband’s recent condemnation of Israel over the use of fake British passports in the Dubai assassination of a senior Hamas terrorist. To add to Dismore’s woes, the Muslim Public Affairs Committee is encouraging its supporters in Hendon to vote for anyone but him. So a curious combination of Jewish votes and Muslim votes for Matthew Offord, his Conservative challenger, could hand the seat to the Tories.

But in a nationwide political contest as knife-edge as the present one appears to be, it isn’t only in recognisably “Jewish” constituencies that Jewish votes count. Jewish voters might prove critical to outcomes in seats as far apart as “Jewish” Bury South (where Ivan Lewis, Miliband’s second-in-command, is facing a very strong challenge from Michelle Wiseman, chief executive of Manchester Jewish Community Care) and East Renfrewshire, Glasgow, in which the comparatively tiny Jewish community may be persuaded to save Jim Murphy, the Scottish secretary, who is, naturally, a leading light in Labour Friends of Israel.

Whatever the present Anglo-Jewish leadership may wish, the Jewish vote, in other words, is very much alive and well.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/apr/19/jewish-vote-really-does-count, 19 April 2010