Europol ask for information because gunman wrote of visiting London for secret far-right gathering in 2002

Vikram Dodd and Matthew Taylor

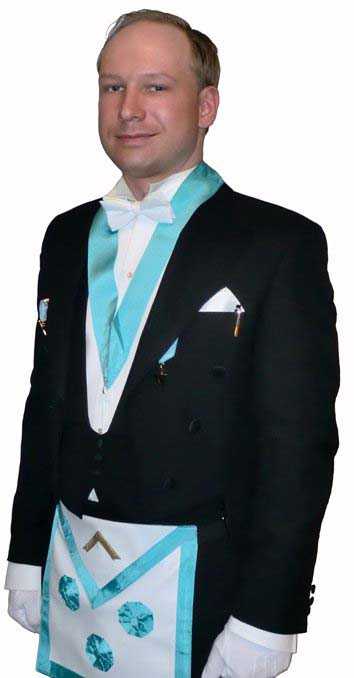

Police attempting to piece together Anders Behring Breivik’s links to far-right groups in the UK and Europe have written to Scotland Yard asking for more officers to help with the investigation.

A specialist unit has been set up in The Hague to trawl through a database of known high-risk, rightwing extremists and assist the Norwegian police as they examine evidence from Breivik’s 1,500-page “manifesto” published online hours before he launched one of the worst mass killings in peacetime Europe.

Rob Wainwright, director of Europol, told the Guardian he had written to the Metropolitan police’s new head of counter-terrorism, Cressida Dick, asking for more officers from Scotland Yard after Breivik boasted of his links to far-right groups in the UK.

“What we’ve seen is an active extremist scene across European countries, including the UK,” said Wainwright. “There are some signs the extreme right have been more active, especially on the internet. They are more sophisticated and using social media to attract younger people.”

There are up to 50 officers already assigned to the specialist unit in The Hague, including a small number of detectives from the UK.

Breivik’s alleged links to the UK emerged in his manifesto, which details his years of meticulous planning prior to Friday’s attacks. The document was signed “Andrew Berwick” (an anglicised version of his name), written entirely in English, and datelined “London, 2011” – although security services and police say there is no further evidence at this stage to suggest it was written in the UK.

In the manuscript Breivik describes his “mentor” as an Englishman he identifies as “Richard”, and says his journey into violent extremism began at a small meeting in London in 2002 where a group of like-minded extremists met to “reform” the Knights Templar Europe, a military group whose purpose was “to seize political and military control of western European countries and implement a cultural conservative political agenda”.

The group’s name is a reference to the medieval Christian military order involved in the Crusades. It has no connection to the Knights Templar International, a long-established organisation aiming to build “bridges throughout the world for peace and understanding”, and which has issued a statement deploring Breivik’s “senseless acts of terrorism”.

In his manifesto Breivik said the gathering in London was “not a stereotypical ‘rightwing’ meeting full of underprivileged, racist skinheads with a short temper”. Instead, he claimed those present were successful entrepreneurs, “business or political leaders, some with families, most Christian conservatives, but also some agnostics and even atheists”.

Breivik said the handful of far-right activists had travelled to London from across Europe, and most had not met each other before. He did not name those present, but claims two of them, including the host, were English, as well as one French, one German, one Dutch, one Greek, one Russian and one Serbian.

“They obviously wanted resourceful, pragmatical [sic] individuals who were able to keep information away from their loved ones and who were not in any way flagged by their governments.”

At 23 years old, Breivik says he was the youngest person at the meeting, and had first been put in contact with others in the group by a “Serbian crusader commander”.

At the end of the sessions, he says, he was “ordinated as the 8th justicar knight for the PCCTS, Knights Templar Europe” – the name he uses to sign off the last entry in his diary before carrying out Friday’s attacks.

It was at this meeting that he also claims to have struck up his friendship with his mentor. Breivik says he and “Richard”, who took the pseudonym in reference to Richard the Lionheart, had a “relatively close relationship”.

According to the document, the meeting in London was followed by two larger events held in “Balticum” which attracted people from all over Europe. He says there was a high level of security at the gatherings, adding that those attending were told not to communicate to people outside.

“Some of us were unfamiliar with each other beforehand, so I guess we all took a high risk meeting face to face … electronic or telephonic communication was completely prohibited, before, during and after the meetings. On our last meeting it was emphasised clearly that we cut off contact indefinitely. Any type of contact with other cells was strictly prohibited.”

Breivik also boasted about links to the UK far-right group the English Defence League. He mentioned the group several times in the manifesto and claimed he had “spoken with tens of EDL members and leaders … [supplying] them with processed ideological material (including rhetorical strategies) in the very beginning.”

The EDL – which has staged a series of street demonstrations, many of which have turned violent, since it was formed two years ago – issued a statement on Sunday condemning the killings and denying any links with Breivik. It added that the league was a peaceful organisation which rejected all forms of extremism.

In the closed court hearing on Monday, Breivik claimed he belonged to an organisation with two more cells that remain at large, although he did not give more details. Wainwright, the Europol director, said police were working flat out to try and establish whether Breivik had help from far-right groups and activists in the UK and across Europe.

“We’re pursuing a number of lines of inquiry. It is difficult to tell if he had active support from outside Norway,” he said.

www.guardian.co.uk, 25 July 2011