Only days after Greek Prime Minister Antonis Samaras went to Turkey to meet his counterpart, Recep Tayyip Erdogan to try to resolve differences over gas and oil exploration in the sea between the countries, a further breach has developed. The newspaper Kathimerini reported that Greek Foreign Minister Dimitris Avramopoulos and his Turkish peer, Ahmet Davutoglu are going to have to keep negotiating.

They said they were hopeful of a resolution, usually viewed as diplomatic language to mean the differences are difficult to overcome but they want to put a positive spin on it for the public. They told the newspaper in separate interviews they would keep talking although Greece is insisting on using international law regarding the seas that Turkey does not subscribe to. Ankara wants a bilateral agreement for the creation of an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in the Aegean.

The foreign ministers of Greece and Turkey told Sunday’s Kathimerini in separate interviews that they are hopeful the two countries can resolve their differences in the Aegean, although Athens is using international law as its guideline for the creation of an exclusive economic zone (EEZ), while Ankara wants there to be a bilateral agreement.

“We are in discussions and searching for common ground because both sides understand how great the benefit would be if we are able to delineate the continental shelf between us from Evros to Kastellorizo,” said Avramopoulos.

“We have some different views and approaches to how the exclusive economic zone or other sensitive issues are defined,” Davutoglu said. “We know there are differences of opinion. The important thing is whether we will let these be an obstacle, like a Berlin Wall, which is not sustainable, logical or ethical.”

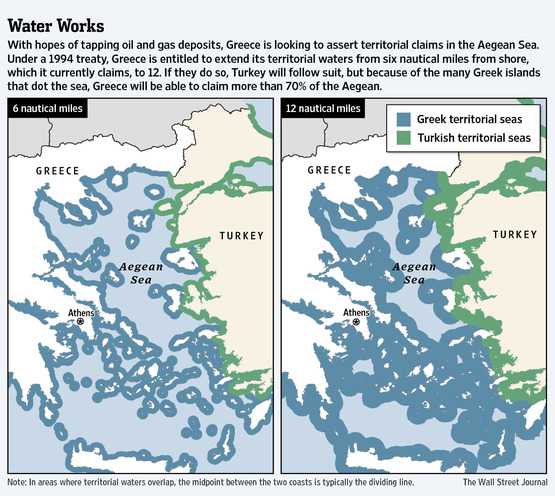

Turkey argues that Greek islands close to its coast should not be taken into account when determining the economic zone and that the median line of the Aegean should be set as a boundary. Greece claims the Law of the Sea means that all islands must be taken into account when setting out the EEZ.

“We are operating based on our planning and strategy, with the framework of our sovereign rights as derived from international law,» said Avramopoulos. “Nobody should doubt our willingness and determination to defend this. International law is our gospel.”

“Of course international law and national sovereignty form the backbone of these negotiations but… the best way to solve these problems is through bilateral dialogue because the Aegean is a particular case with thousands of islands and at the same time is part of the wider Mediterranean,” said Davutoglu.

“Turkey has the longest coastline in the Mediterranean,” he added. “Nobody can expect Turkey to remain landlocked due to certain measures. We can find a solution whereby all these islands and Turkey’s interests as the country with the longest coastline in the Mediterranean can be taken into account. These are not conflicting positions.”

Greece recently sent a diplomatic note to the United Nations complaining that Turkey had issued permits to a state-run company to search for gas and oil in areas covering the Greek continental shelf. Avramopoulos was adamant that Athens would resist any attempts by Turkey to go ahead with such plans.

“It has been proven that unilateral moves, which are outside of the framework of international law, do not help and should be avoided,” he said. “We will not accept actions that challenge our sovereign rights. Such a development would have serious consequences for our bilateral relations at a time when both sides are trying to create a basis for cooperation in many areas.”

Davutoglu indicated that Ankara had no intention of causing rifts with Greece or of taking advantage of any weaknesses caused by its economic crisis. “We want to see a strong, stable and prosperous neighbor next to us. Some extremists in Greece or Turkey may think this is a zero-sum game but I can assure you that it is quite the opposite,” he said.

“In the 60s, 70s, 80s and even 90s, this mentality existed but things have changed now. Young Greeks watch Turkish soap operas and Turks go to Greek islands for holidays,” added the Turkish foreign minister.

via Greece, Turkey Can’t Agree On Sea Deal | Greece.GreekReporter.com Latest News from Greece.