By Arnold Reisman

Mr. Reisman PhD is listed in Who’s Who in America, and is a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He published over 300 papers in refereed journals and seventeen books. His latest books are: TURKEY’S MODERNIZATION: Refugees from Nazism and Atatürk’s Vision and Classical European Music and Opera. He is currently working on two other titles. They are: PERFIDY: Britannia and Her All-Jewish Army Units and Ambassador and a Mentsch: The Story of a Turkish Diplomat in Vichy France.

During World War II, Turkish diplomats saved Turkish Jews living in France (many were French citizens others were holding Turkish passports) from certain death, a fact of which the Anglophone world was ignorant until Stanford Shaw first revealed the historical data in 1995.1 Up until that time, this important piece of history had been ignored by historians. Mistakenly however, Shaw attributed the actions of Turkey’s legations in both occupied and Vichy France to a well articulated policy created by the Turkish government in Ankara, when in fact these brave acts of heroism were devised by the diplomats themselves as a matter of conscience. In fact, from the outset of these actions the Turkish government had to be prodded and pushed, with various ramifications including implied aid programs from a number of sources, to acquiesce from outside of Turkey not from within. The diplomats involved were: Behiç Erkin, Turkish ambassador to Paris and later to Vichy; Necdet Kent, Consul General in Marseilles; Paris Consul-Generals Cevdet Dülger, Fikret Sefik Özdoganci, and Paris Vice Consuls Namik Kemal Yolga, Fatin Rüştü Zorlu and Melih Esenbel; Marseilles Consul Generals Bedi’i Arbel, and Mehmed Fuad Carim.2

Recent findings of many contemporaneous documents from the NARA, Library of Congress, and the FDR Presidential library archives attest to the fact that the intervention in behalf of French Jews with Turkish origins was not the policy of the Government of Turkey at all. Rather, it was the determined undertaking of members of the Turkish diplomatic corps who acted on their own against the extant policy of their own government and that of the US and the UK. These men of conscience risked their careers and often their lives finding no support among their diplomatic peers representing western countries including those in the US legation. With their deeds these diplomats risked the wrath and ire of their own government as well as Germany and Vichy France.

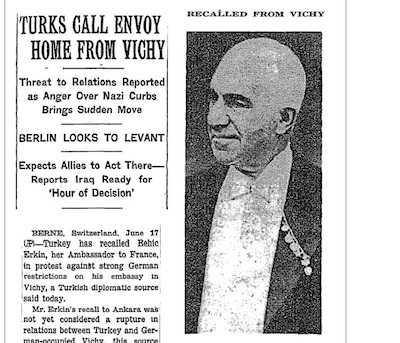

While Germany and Vichy France were anti-Semitic to their cores, Turkey was in the unenviable position of attempting to maintain neutrality while in dire fear of being invaded by Germany. For that reason and after great pressure from Germany, Ambassador Behiç Erkin was recalled to Ankara and the rate at which Jews were repatriated to Turkey was greatly diminished. Many Jews were saved by the acts of the Turkish legation in France. From March 15, 1943 through May 23, 1944, the Turkish Embassy in Vichy and Consulates-General in Paris arranged for no fewer than eight groups of former Turkish Jews averaging roughly fifty-three persons each to be returned to Turkey and to freedom by rail in sealed wagons. This is but a part of claims that all 20,000 Turkish Jews residing in France were saved. Looked at in reverse the known number of Turkish Jews deported from France to the death camps is 1659.

To fully appreciate the actions taken by Behiç Erkin and his staff, one need only look at the fate of Jews in Thesalonika, Greece. During WWII Greece was occupied by the Nazis but neutral Turkey maintained an Embassy in Athens and a Consulate in Thesalonika. Before the war Thesalonika boasted a Jewish population of 56,000, most with roots in the Ottoman Empire dating back to the Spanish Inquisition and the expulsion of Spanish Jewry in 1492. These Jews were no different than those in France, many of whom were saved by Behiç Erkin and his staff while the entire Thesalonika Jewish community was deported to the crematoria. Why did the Turkish legation in Greece not raise objections? They did not interfere since they had no instructions from Ankara to do so, and obviously lacked the moral compass that guided their colleagues in France.

As the war continued the Nazis began persecuting French Jews. Many “Turkish Jews” who had relinqueshed their Turkish citizenship “suddenly found it was far better to be a Turkish Jew than a French Jew, and they applied in large numbers to have their Turkish citizenship restored.”

According to a Raoul Wallenberg Foundation website:

Turkish diplomats serving in France at that time dedicated many of their working hours to Jews. They provided official documents such as citizenship cards and passports to thousands of Jews and in this way they saved their lives.

Below is a story of these diplomats.

Behiç Erkin was the Turkish ambassador to Paris when France was under Nazi occupation. In order to prevent the Nazis from rounding up Jews, he gave them documents saying their property, houses and businesses, belonged to Turks. He saved many lives in this way.

Pressure mounted for Turkey to recall her Ambassador from France as he was deemed unmanageable.

Was it a coincidence that Behiç Erkin “resigned” from his posting to France on the 23rd of August 1943 and three days later from the Foreign Service altogether? There is no question but that Erkin was removed from the Ambassadorial post because of Ankara’s inability to withstand Germany’s pressure and the implied threat of invasion. For Turkey, angering Berlin meant more than risking the loss of lucrative exports at a time when its economy was still in shambles. There was also a real and present danger that Germany could opt to use Turkey as a route to the Caspian area oil riches in order to hit the Soviets on another front – its soft underbelly. This was indeed a real possibility, not just conjecture. Turkey’s army stood prepared.

In a letter dated September 2, 2008, to Abdullah Gul, President of the Republic of Turkey, the Raoul Wallenberg Foundation’s Founder, Baruch Tenenbaum, stated “we are conducting an extensive research into the actions of the Turkish diplomats who were stationed in France during WWII, including Ambassador Behic Erkin, Consul Bedi’i Arbel and Vice Consul Necdet Kent, just to name a few.” At the time this article was written, that “research” was still ongoing. It is this author’s humble opinion that starting with Behic Erkin, the Ambassador and the “leader of the band” most if not all members of the Turkish legation in France ca 1939-1944 deserve to be honored with Yad Vashem’s “Righteous Gentile” Award.

Shaw, S.J. Turkey and the Holocaust, (London: Macmillan Press,1993)

Shaw Turkey and the Holocaust; Kıvırcık The ambassador:

Anonymous, Proceedings of the Second Yad Vashem International Historical Conference on Rescue Attempts During the Holocaust, held in Jerusalem, 8-11 April 1974

“Notes from the Leahy diary,” US Ambassador in Vichy, France, William D. Leahy papers, Library of Congress All diary entries for 1941: Reel 2, William D. Leahy Diaries, 1897-1956, (Washington DC: Library of Congress), microfilm. All diary entries for 1942 and letters to Welles: Reel 3, William D. Leahy Diaries, 1897-1956, Washington DC: Library of Congress), microfilm. Entries for: Jan. 1 – p.2; Jan. 8 – p. 4; March 5 – p.29; April 14 – p. 46; April 25th – p. 52. For July 18, 1941 letter to Welles – p. 2; Sept. 13, 1941 letter to Welles – p. 3.

Source: History News Network, 02.11.2009,

http://hnn.us/articles/118548.html

(ANSAmed) – BRUSSELS – An appeal was launched today in Brussels by the ‘wise men’ of the Independent Commission on Turkey to restart negotiations on EU membership with Ankara, which have been caught in a vicious circle for four years. The wise men – former Finnish President and Nobel prizewinner for Peace Martti Ahtisaari; fomer EU Commissioner Emma Bonino, Italy, and Hans van den Broek, Holland; former French Premier Michel Rocard; former Spanish Foreign Minister Marcelino Oreja; Austria’s former Secretary General for Foreign Affairs Albert Roahn – presented their report ‘Turkey in Europe, breaking the vicious circle’, taking the opportunity to make observations on the recent turbulent years in relations between Ankara and the EU. It all started with a ‘paradox’, said Rohan: ”Since negotiations started in 2005, the virtuous circle has turned into a vicious circle”. There are several reasons for this change of tack: the thorny issue of Cyprus, with the failed 2004 referendum over the reunification of the island following the ‘no’ vote by the Greek-Cypriots, the slowing-down of reforms by Ankara, and also ”the opposition to Turkey’s entry on the part of several European leaders and public opinion in many countries”. The positions of the leaders, said Rohan, ”are in stark contradiction to the unanimous decision to open adhesion negotiations taken by heads of State and government in December 2004. This attitude has given Turkey the impression of not being wanted, of being treated differently from other candidates. But this approach is contrary to European interests: Turkey is a strategic country for energy routes, its presence in the Caucasus, its economic strength in Central Asia, and its negotiating weight in the Middle East”. The result is that now more than half of the 35 chapters of negotiations for adhesion are blocked, either because of Cyprus’ veto, as a response to the lack of full application of the Ankara Protocol on the part of Turkey, which regulates customs relations with the 27 countries, or because of the block placed informally by other chapters. France has blocked five chapters, preferring to focus on partnership rather than integration. Austria, Germany and Holland also have political positions or public opinion overwhelmingly against Turkey’s inclusion in the EU. As for Italy, Bonino said that ”lately, for the first time, opposing positions have been taken very very firmly by the Northern League”. For this reason the former EU commissioner has called on Berlusconi to ”mediate” inside the Government so as to define a clear position ahead on the EU summit on December 9-10, during which the next steps for the adhesion talks will be defined. Emma Bonino said that the question ”of identity is an alibi for not saying anything, for not saying that they are Muslims, there are 80 million of them. I always feel like saying, what is the European identity? For me, Europe is a State of rights, division of power, democracy, open society; I do not believe that Europe is a religious project or a geographic project”. In this negative context, there are only a few signs of a change in tendency, for example the resumption of Turkish-Armenian dialogue. But the ‘wise men’ insist that ”an effort is needed, we need good news from Turkey, on its reform plans, and a greater sense of responsibility on the part of the authorities and the European media”. ‘‘Not just the credibility of Europe towards Turkey, but the international role of the EU are at stake”, concluded Ahtisaari. (ANSAmed).

(ANSAmed) – BRUSSELS – An appeal was launched today in Brussels by the ‘wise men’ of the Independent Commission on Turkey to restart negotiations on EU membership with Ankara, which have been caught in a vicious circle for four years. The wise men – former Finnish President and Nobel prizewinner for Peace Martti Ahtisaari; fomer EU Commissioner Emma Bonino, Italy, and Hans van den Broek, Holland; former French Premier Michel Rocard; former Spanish Foreign Minister Marcelino Oreja; Austria’s former Secretary General for Foreign Affairs Albert Roahn – presented their report ‘Turkey in Europe, breaking the vicious circle’, taking the opportunity to make observations on the recent turbulent years in relations between Ankara and the EU. It all started with a ‘paradox’, said Rohan: ”Since negotiations started in 2005, the virtuous circle has turned into a vicious circle”. There are several reasons for this change of tack: the thorny issue of Cyprus, with the failed 2004 referendum over the reunification of the island following the ‘no’ vote by the Greek-Cypriots, the slowing-down of reforms by Ankara, and also ”the opposition to Turkey’s entry on the part of several European leaders and public opinion in many countries”. The positions of the leaders, said Rohan, ”are in stark contradiction to the unanimous decision to open adhesion negotiations taken by heads of State and government in December 2004. This attitude has given Turkey the impression of not being wanted, of being treated differently from other candidates. But this approach is contrary to European interests: Turkey is a strategic country for energy routes, its presence in the Caucasus, its economic strength in Central Asia, and its negotiating weight in the Middle East”. The result is that now more than half of the 35 chapters of negotiations for adhesion are blocked, either because of Cyprus’ veto, as a response to the lack of full application of the Ankara Protocol on the part of Turkey, which regulates customs relations with the 27 countries, or because of the block placed informally by other chapters. France has blocked five chapters, preferring to focus on partnership rather than integration. Austria, Germany and Holland also have political positions or public opinion overwhelmingly against Turkey’s inclusion in the EU. As for Italy, Bonino said that ”lately, for the first time, opposing positions have been taken very very firmly by the Northern League”. For this reason the former EU commissioner has called on Berlusconi to ”mediate” inside the Government so as to define a clear position ahead on the EU summit on December 9-10, during which the next steps for the adhesion talks will be defined. Emma Bonino said that the question ”of identity is an alibi for not saying anything, for not saying that they are Muslims, there are 80 million of them. I always feel like saying, what is the European identity? For me, Europe is a State of rights, division of power, democracy, open society; I do not believe that Europe is a religious project or a geographic project”. In this negative context, there are only a few signs of a change in tendency, for example the resumption of Turkish-Armenian dialogue. But the ‘wise men’ insist that ”an effort is needed, we need good news from Turkey, on its reform plans, and a greater sense of responsibility on the part of the authorities and the European media”. ‘‘Not just the credibility of Europe towards Turkey, but the international role of the EU are at stake”, concluded Ahtisaari. (ANSAmed).

TEHRAN (FNA)- The US and Israeli spy agencies are trying to promote evangelism in Iraq’s Kurdistan region, sources said.

TEHRAN (FNA)- The US and Israeli spy agencies are trying to promote evangelism in Iraq’s Kurdistan region, sources said.