Ivan Dikov

Interview with Michal Parzyszek, Spokesperson of EU border control agency Frontex based in Warsaw on the situation of EU‘s external borders and illegal migration.

Could you provide brief information the operations that the EU border control agency Frontex is carrying out at the moment? How many are they and what is their geographical scope?

There are some operations that I am unable to talk about for operational reasons; these are operations that we present to the public only after they are finalized.

As regards the operations along the southern borders, which are the focus of the European citizens because of the tragedies which are happening at sea, we have Operation Hera, which is in the territorial waters of Senegal and Mauritania; Operation Indalo in Spanish waters; Operation Hermes in Italian waters; Operation Aeneas in Italian waters; Operation Poseidon in Greek waters.

When it comes to land operations – there is Operation Poseidon in Greece and Bulgaria; and one more operation at the Eastern borders of the EU which is hosted by many countries but here I will not go into details. There are also operations at airports, and again, I will not enter into details here.

How has the situation on the ground in Northeastern Greece changed since Frontex started to patrol there? Has the influx of migrants decreased substantially?

The flow of illegal migrants in Northeastern Greece is rather constant – it varies from 70 to 100 persons a day. This is the daily average of people that are detected and apprehended at the Greek-Turkish land border. The waters of the Evros River (Maritsa River) are shallow, so that is a factor that pushes people to cross the border there.

The situation has changed from September 2010 when they crossed close to Orestiada; now they are more likely to try to cross the river to the south in the direction of the city of Alexandroupolis.

With the unrest in North Africa and the Middle East continuing, Italy has become the new hot spot bearing the brunt of illegal migration. How have Frontex‘s efforts in southern Italy helped to alleviate the situation?

The help on part of Frontex in the southern waters, including in Italy, is more on providing risk analysis – to give a better idea of what is going on, and what can happen.

In terms of operational assets, Italy has really well-equipped services – Guardia Costiera, Guardia di Finanza, Polizia di Stato, Carabinieri – there are many authorities.

So in terms of assets, there are just two airplanes and two boats which are deployed there under Frontex in the waters south of Sardinia and south of Lampedusa.

But the important contribution is those experts that are mentioned. There are 10-15 Frontex experts that are identifying the migrants once they reach the reception facilities there. They are deployed to Caltanissetta, Catania, Trapani, Crotone, and Bari. There are the reception centers for migrants. The Frontex experts are helping Italian authorities to identify them.

What about the influx of migrants in Southern Italy – is it constant, receding, or increasing?

It varies every day. You have days when you have no arrivals, and then suddenly you have 1 000 people arriving to Lampedusa. Since the start of the operation on February 20, 2011, there have been almost 31 000 people that arrived to Lampedusa. That is quite a number.

When the Land Operation Poseidon in Greece was made permanent in March 2011, the EC said it will be extended to the Bulgarian-Turkish border. How has that been carried out? Have any Frontex officers or equipment been located on Bulgarian territory, i.e. the Bulgarian Turkish border?

There are already experts on there ground from Belgium, the Netherlands, Romania, Germany, and Austria working in the Svilengrad border crossing point unit.

They are mainly deployed to the Bulgarian border crossing point of Kapitan Andreevo because this is the main point where you detect people trying to use fake ID documents or trying pass hidden inside vehicles. So they are working there.

What is Bulgaria’s situation with respect to the challenge that it is likely to face with illegal migrants? Should Bulgaria be worried about that and expect a Greek scenario?

There are quite many factors influencing the influx of migrants. One of them, which is very important, is readmission agreements.

In the case of Greece, a readmission agreement with Turkey doesn’t truly work; in the case of Bulgaria, the cooperation with Turkey is much better so the Turkish authorities – if they receive proper documentation and justification – they accept people back.

This is a very important element – potential migrants know that if they cross the border between Turkey and Bulgaria, there is high probability that they will be sent back to Turkey so they don’t choose that way.

That’s one factor. The other factor is that Bulgaria is not fully within the Schengen Area yet, which means that migrants can expect more border checks on the way so they choose Greece.

How is Bulgaria’s situation in terms of attracting the flow illegal migrants going to change once it joins the Schegen Area?

Yes, there is certainly the question of what will happen when Bulgaria fully joins Schengen.

This is a bit like looking into a crystal ball but of course our risk analysis experts always view each expansion of the Schengen Area as a risk.

The only thing you can do is keep border guards alert and observe the situation. But knowing how much money Bulgaria invested in new border equipment, and knowing how border guards in Bulgaria are trained, I wouldn’t worry so much.

Other than Greece and Italy and Malta, what other hot spots of illegal migration can be expected? Bulgaria, Romania, the Baltics, Spain, Portugal?

The biggest issue is actually invisible. This is something that is always omitted. These are international airports. The majority of the people that are apprehended within the Schengen Area that are staying illegally actually come in legally by plane, and then overstay their visas.

In terms of people staying illegally on the territory of the European Union, this is for sure the biggest issue. No one really has numbers how many people are overstaying their visas but their numbers are certainly much higher than the number of illegal immigrants detected at sea or land borders. This is absolute number one concern.

In terms of illegal border crossings – in 2010 Greece – it was 86% of the illegal border crossings in the EU. No. 2 on the list was Spain with about 5 200 persons, and then Italy with 4 500 persons. That’s the two three for last year. Looking at the situation now, it looks like Italy will remain the most affected country in terms of illegal crossings.

What about the Central European and Baltic borders of the EU?

The situation there is fairly stable. You have some people crossing illegally into Hungary but these people crossing mainly from the Western Balkans. I think that Poland is No. 9 or 10 on the list of illegal border crossings but we are talking about 150 persons a year so nothing that can compare with 90 000 people in Greece. The situation there is really stable.

Again, it is about the geographic position. The border is managed from two sides. If you have a neighbor such as Russia or Belarus where the border control is very strong, it is a bit like army-based, then the border on the other side is simply impermeable.

How do you expect the role of Frontex to be expanded? Is it expected to acquire more powers, more responsibilities because obviously these issues aren’t going away?

The discussion in the Council and the European Parliament is still going on, but if you listen to the voices from Brussels, it looks like there will be some kind of an agreement very soon, and probably over the summer the new regulation for Frontex will be adopted.

Then we will try to define the legal terms into practical actions but it will take some time for sure. As of the moment of accepting new regulations and giving new tasks to Frontex, we will need some time for translating the law into reality.

Source: http://www.thebulgariannews.com/view_news.php?id=128635

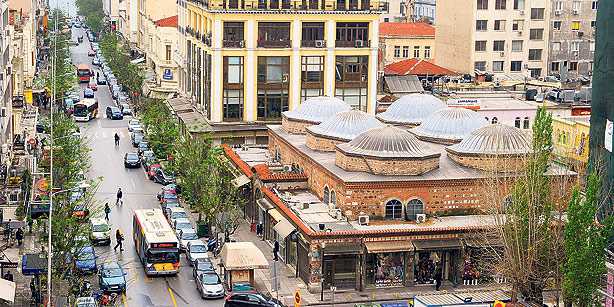

Greek troops arriving at Salonica, now Thessaloniki, in 1915The owner was a refugee, too. But his family had come from Smyrna, now Izmir in Turkey. His Borekci grandfather had taken over from a man who had been given the key by a blond-haired Turk the day he and his family were deported in 1924 with the last of the city’s Muslims. And yes, the bougatsa was fit for a bishop.

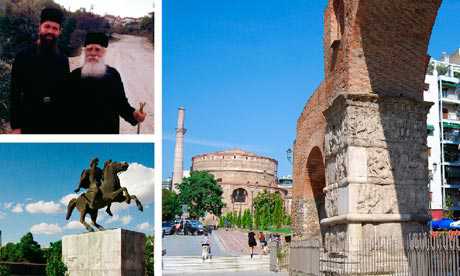

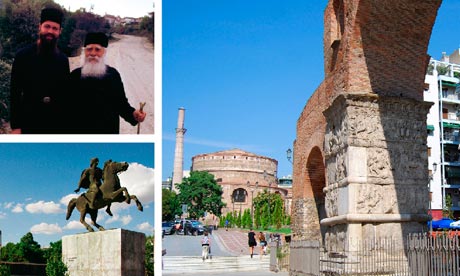

Greek troops arriving at Salonica, now Thessaloniki, in 1915The owner was a refugee, too. But his family had come from Smyrna, now Izmir in Turkey. His Borekci grandfather had taken over from a man who had been given the key by a blond-haired Turk the day he and his family were deported in 1924 with the last of the city’s Muslims. And yes, the bougatsa was fit for a bishop. The church of St GregoryNothing is quite what it seems. To really see Thessaloniki for what it is, you have to see not just the living but the dead. You have to look out towards Olympus and the mists that roll in off the Thermaic Gulf and see Pierre Loti rowing Aziyadé away from her husband; or see the last true sultan, Abdulhamid II, step ashore into house arrest from the imperial caique with his harem and carpentry tools in tow (as well as being a paranoid, bloodthirsty tyrant, he was a very nifty cabinet maker).

The church of St GregoryNothing is quite what it seems. To really see Thessaloniki for what it is, you have to see not just the living but the dead. You have to look out towards Olympus and the mists that roll in off the Thermaic Gulf and see Pierre Loti rowing Aziyadé away from her husband; or see the last true sultan, Abdulhamid II, step ashore into house arrest from the imperial caique with his harem and carpentry tools in tow (as well as being a paranoid, bloodthirsty tyrant, he was a very nifty cabinet maker).