Inside the European pipeline fantasy that became a real-life gas war with Russia.

www.foreignpolicy.com

August 24, 2009

BY DANIEL FREIFELD

Daniel Freifeld is director of international programs at New York University’s Center on Law and Security.

When Joschka Fischer’s lucrative new job as the “political communications advisor” to a consortium of European energy companies was leaked to a German business publication this summer, there was one comment that stood out. “Welcome to the club,” said Gerhard Schröder, an even more highly paid advocate for the other side in Europe’s increasingly politicized energy war.

Schröder’s remark was short, snide — and very much to the point. For eight years, the two men had led Germany together, with Schröder ruling as its center-left chancellor and Fischer as his foreign minister. Their long-running partnership had survived a particularly complicated era in post-Cold War Europe, and publicly Fischer had always been supportive, even telling Der Spiegel that Schröder “will go down in the history books as a great chancellor.”

But since their coalition government collapsed in 2005, Schröder’s controversial work has led to an ever-more-public breach between the former allies. Less than one month before leaving the chancellorship, Schröder used his office to guarantee a $1.4 billion loan (later turned down) for a Kremlin-backed natural gas pipeline that would connect Russia to Germany via the Baltic seabed. Then, just days after stepping down, Schröder accepted a senior post with the pipeline consortium run by Russia’s state gas monopoly Gazprom. The deal was a huge scandal inside Germany, where Schröder had already been known for years as Genosse der Bosse — “comrade of the bosses.”

The chancellor’s move to the Kremlin energy payroll inspired a wave of alarm in Europe over its potentially dangerous dependence on Russia for natural gas. Moscow supplies about a third of the European Union’s gas — Europe’s preferred heating source — and some of its countries are 100 percent dependent on Russia. What’s more, Europe’s annual gas consumption is set to rise 40 percent by 2030, further stoking those fears about Russia. Several times in recent years, the Kremlin has abruptly cut off gas deliveries after disputes with key transit countries such as Ukraine, leaving millions of Europeans shivering in the winter cold.

Schröder had been reliably pro-Russia while in office, even famously calling the KGB-spy-turned-president Vladimir Putin a “flawless democrat.” Although Fischer did not criticize his boss publicly at the time, more recently he has been openly dismissive. Schröder’s idea of Putin as a democrat, Fischer told the Wall Street Journal, “was never my position.” Asked later by Der Spiegel what he found “most objectionable” about Schröder’s tenure, Fischer replied succinctly: “His position on Russia.”

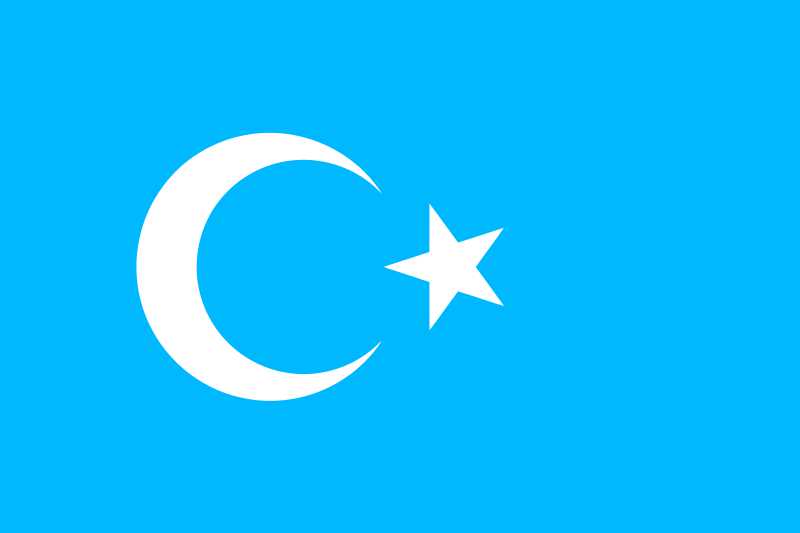

This summer, Fischer made the breach with Schröder official: He signed up with a rival consortium — energy companies from Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, and Austria that have joined together to build the $11 billion Nabucco natural gas pipeline. Nabucco would bring gas from Middle Eastern and Caspian fields across Turkey’s Anatolian plateau, and north into Europe. The pipeline is backed and partly funded by the EU and is strongly supported by the United States. Perhaps most importantly, Nabucco would completely bypass Russia. Such an energy strategy, Fischer has argued, is urgently needed to stop Moscow’s “divide-and-conquer politics.”

Moscow, not surprisingly, is pulling out all the stops to scuttle the project. It is seducing pliant politicians and resorting to old-fashioned bullying, especially in the states that Nabucco transits. It is acquiring stakes in European energy companies, often through questionable shell companies, that could complicate Nabucco’s completion. It is buying up natural gas in Central Asia and the Caspian, even paying up to four times more than in previous years, to deny supplies to Nabucco. And it has proposed a rival pipeline, called South Stream, which would flow from Russia across the Black Sea to Bulgaria and the Balkans and fork, with one spur running west to Italy and the other north to Austria.

In many ways, Schröder and Fischer personify the intense struggle — some call it a war — over Europe’s energy future. On one side are those countries most worried about their dependence on Moscow, especially the former communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe. On the other are countries such as Italy and Germany and leaders such as Schröder, who see closer ties with Russia as both a mercantilist opportunity and a strategic imperative. When I caught up with Schröder at a conference in Houston earlier this year, he was quick to brush aside concerns about Moscow. “There is no reason to doubt the reliability of Russia as a partner,” Schröder said. “We must be a partner of Russia if we want to share in the vast raw material reserves in Siberia. The alternative for Russia would be to share these reserves with China.”

This gas war is especially hard-fought because of the physical nature of the prize itself. Unlike oil, which can be put onto tankers and shipped anywhere, gas is generally moved in pipelines that traverse, and are thus tethered to, geography. Because a pipeline cannot be rerouted, producers and consumers sign long-term agreements that bind one to the politics of the other, as well as to the transit states in between. In this way, today’s gas war is a zero-sum conflict similar to the scramble for resources that divided Eurasia in the 19th century. And now, as then, commerce is taking a back seat to politics.

That is what I found when I set out this spring to travel the pipeline routes, encountering along the way a rogue’s gallery of cynical politicians, murky middlemen, insistent executives, and innumerable technocrats, each eager to shape the decision. But the real question that will determine Nabucco’s future — a question vividly on display in every country the pipeline will touch — is whether Europe has the stomach to fight as hard for its interests as Russia does for its own.

One evening in 2002 in Vienna, a small group of Austrian energy executives took their colleagues from Turkish, Hungarian, Bulgarian, and Romanian firms to see a rarely performed Verdi opera. It recounted the plight of Jews expelled from Mesopotamia by King Nebuchadnezzar. The officials had spent the day sketching out a plan for a 2,050-mile pipeline that could transport up to 1.1 trillion cubic feet of natural gas every year across their countries and into European markets. The sources of this gas would not be Russia, but Azerbaijan, maybe Iran one day, and with a U.S.-led war against Saddam Hussein looking increasingly likely, possibly the gas fields of northern Iraq. The opera they attended that night was called Nabucco, and that is the name they gave their pipeline.

The original impetus for the project was just business: The Turks and Austrians saw it as a way to get new supplies of gas from the Caspian and Middle East — not to mention lucrative transit fees for moving it across their territories into Europe. But politics soon entered into it, as Nabucco won early moral support from Russia skeptics in Central and Eastern Europe. They saw the pipeline as a historic opportunity to build a new lifeline to the West while weakening Russia’s grip on them. Many worried, as former Estonian Prime Minister Mart Laar wrote, that “Russian leaders regard their energy assets as tools of foreign-policy leverage and envisage a future in which resource competition may be resolved by military means.” The main energy firms in Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary — all countries that would host Nabucco — signed on to help build the pipeline.

The big powers of Western Europe, however, were less dependent on Russian gas and far less willing to antagonize Moscow by bringing non-Russian gas into Europe through former Soviet satellites. Italy, under Silvio Berlusconi, and Germany, under both Schröder and his successor Angela Merkel, dragged their feet on Nabucco. France, with its nicely diversified supply of energy, had little appetite for changing the status quo. Together, these countries blocked any effort within the European Union to allocate funding for Nabucco or even make support for the pipeline a common policy. This resistance infuriated the European Union’s newest members, and it still rankles. “The EU role has been weak,” Mihaly Bayer, Hungary’s special representative for Nabucco, told me. “The EU coordinator for Nabucco, Jozias van Aartsen, simultaneously serves as the mayor of The Hague!” Bayer thundered when we talked in his Budapest office. “When I assumed my post, I sent him multiple letters offering my assistance. I even spent two days in The Hague trying to meet with him. He ignored me.”

This east-west deadlock held until 2006, when events started to push in Nabucco’s favor. The reason had everything to do with Ukraine, which has clashed repeatedly with Russia in recent years.

Eighty percent of natural gas from Russia travels to Europe through Ukraine, across an energy infrastructure built by the Soviet Union after the 1956 Hungarian uprising. The main pipelines converge in Ukraine before fanning out into Eastern Europe, and were key to the Kremlin’s strategy of controlling its Warsaw Pact satellites. The route went through Ukraine because Soviet planners never imagined a day when Ukraine would not be ruled by Moscow. But when that day did arrive, on Aug. 24, 1991, Russia’s hold on Ukraine did not end. It just grew more complex, and gas remained a central means of control.

How this unfolded was explained to me in Kiev by Bohden Sokolovsky, an energy advisor to Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko, over a breakfast of vodka, blintzes, and cigarettes. It all came down to two things, Sokolovsky said, “Otkat and deriban” — roughly translated, kickbacks and theft. As Soviet assets and state-run energy companies were privatized in Ukraine in the 1990s, apparatchiks and businessmen on both sides of the border concocted elaborate schemes to get in on the action. They manipulated prices and parceled out kickbacks. The deals were “obviously corrupt,” recalled a senior advisor to former Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma. “But it was a great deal for Ukraine.”

Many Europeans disliked their dependence on Ukraine. “The very basis of the gas business in Ukraine is graft,” Vaclav Bartuska, the Czech Republic’s ambassador at large for energy security, told me. But the desire to do something about it only really materialized with the gas disputes that broke out between Ukraine and Russia after the 2004 Orange Revolution. Ukrainian protesters had just successfully contested an election marred by fraud and voter intimidation, ultimately preventing the Kremlin-favored candidate from taking power. Soon after, the new president, Yushchenko, sought to steer Ukraine into a Euro-Atlantic orbit. This was a direct threat to Russia’s influence over its main point of entry into European gas markets. So Putin countered that if Ukraine wanted to be a Western country, it would have to pay the far higher Western price for gas. When Kiev refused to pay those higher prices in the winter of 2006, Moscow shut off gas shipments to its neighbor for four days, denying fuel to millions of other Europeans as well.

“It wasn’t until the 2006 gas crisis that the rest of Europe actually started to care about what was going on in Ukraine,” recalled Bartuska, who mediated yet another dispute between Russia and Ukraine this January. Many more Europeans began to view Russia not as a reliable supplier of gas but as an aggressive petrostate that privileged its political organizations over its commercial obligations.

Almost overnight, support for Nabucco grew dramatically throughout Europe. But the gas shut-offs also added new impetus to Nabucco’s Russian-backed rival, South Stream. Whereas Nabucco’s supporters saw warning signs in Ukraine about Russian aggression, others saw a corrupt, untrustworthy transit state disrupting Russia’s reliable supply of gas. As Dmitry Rogozin, Russia’s ambassador to NATO, put it: “It’s clear that if Europe wants to have guaranteed natural gas supplies, as well as oil in its pipelines, then it cannot fully rely on its wonderful ally, Mr. Yushchenko.” The Italian energy company Eni led the way, signing on to South Stream in 2007.

And then, of course, there is Germany, where Gerhard Schröder is hardly Russia’s only friend. At the same Houston conference where I saw Schröder, I attended a small breakfast for energy company officials and experts. At the first mention of transit security, Reinier Zwitserloot, a spry German of about 60, shot up and shouted, “The most reliable transit state is the Baltic!” He went on: “As far as I am concerned, Nabucco is nothing but an opera!” I later learned that Zwitserloot had recently been awarded the Order of Friendship of the Russian Federation, Moscow’s highest honor for non-Russian citizens.

In this opera, Turkey has been cast in one of the leading roles. With its indispensable geographic position between the oil and gas reserves of Iraq, Iran, and the Caspian, it is an absolute certainty that Turkey will host major pipelines sooner or later. If Nabucco succeeds, Turkey could be the biggest winner, both economically and geopolitically — a fact not lost on Russia or Europe. Or Turkey.

Until the gas wars began, Turkey had a weak hand: It had been rebuffed for EU membership and depended on Russia for a majority of its natural gas. But now, with the country’s gas demand skyrocketing and Turkish supply contracts with Russia set to expire, Turkey has not been shy in reminding Europe that it has options. “What is important is to gain natural gas,” said Taner Yildiz, Turkey’s minister of energy. But doing it through Nabucco, he added, “is not obligatory.” Turkey’s ambassador to the United States has pointedly called the EU “the biggest impediment to progress on Nabucco’s development.”

When I sat down in late April with Cuneyd Zapsu, a founding member of Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party and a longtime counselor to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, he was openly frustrated with Europe’s wavering about the pipeline. “Turkey has been ready to sign the deal,” he told me. “But every time the consortium agrees, [our Nabucco partners] throw a new term in.”

Zapsu understands Turkey’s delicate but fortuitous position. “Everyone is trying to make Turkey the enemy,” he said. But shifting his gaze out the window and down onto the Bosporus where Europe and Asia meet, Zapsu just smiled. “Everyone loves us.”

The mood is less one of love than of fear in several other countries where Nabucco would run, as Russia has aggressively stepped up its efforts to block the pipeline. Next door to Turkey in Bulgaria — the poorest member of the EU and a transit state for both the Nabucco and South Stream pipelines — Ognyan Minchev, head of the Institute for Regional and International Studies, told me how Moscow threatened the Bulgarians in 2006. Scrap an agreement with Gazprom and sign a new contract with higher prices for Russia and lower transit fees for Bulgaria, they were told, or else the gas would be cut off. “The Bulgarian government is obedient to Russia,” Minchev said. “Bulgaria has put the entire energy system in Russian hands.”

Further along the Nabucco route, in Hungary, Laszlo Varro has similar fears. At dawn one day in April, the tall Hungarian led his small dog around a hilltop park overlooking Budapest, recounting how the Russian energy giant Surgutneftegaz had recently acquired a decisive stake in the Hungarian energy firm MOL, where Varro is head of strategy. “It is one of the least transparent energy companies — in Russia,” he said. Varro’s concern, he explained, is that no one really knows who is behind Surgutneftegaz — or rather, he quickly added, that “everyone knows who is behind the company since no one knows.” Others in Hungary suspect the same, and one major newspaper spelled it out in a recent headline: “Mr. Putin, Declare Yourself.”

Surgutneftegaz is run by Vladimir Bogdanov, an oligarch who managed Putin’s 2000 presidential campaign in western Siberia. The secretive Surgutneftegaz has offered almost twice the market value for its shares in MOL. Varro and others see a sinister reason for this seemingly illogical behavior: MOL is a Nabucco consortium member, and by buying this stake, Surgutneftegaz can cut off funding for the pipeline and cripple it in Hungary.

Russian firms are making similar acquisitions in Austria, which is the proposed end of the road for both Nabucco and South Stream. Centrex Europe Energy & Gas, an opaque gas trading firm with ties to Gazprom, makes its money buying cheap gas from Russia and reselling it for profit in Austria. The German magazine Stern recently traced Centrex’s profits back to a company registered to a phony address at a drab Soviet-style housing block in Russia. And yet, Centrex recently entered into a partnership with Gazprom Germania to take a 20 percent stake in Austria’s Baumgarten trading platform and storage facilities, where the two rival pipelines will literally terminate. Considering that Gazprom already holds a 30 percent share in Baumgarten, this means that Russia’s state-run energy company now controls half of the most important gas storage and distribution system in central Europe — and the future terminus of Eurasia’s competing southern pipelines.

Not every country in Europe is so concerned about Russia, however. In Serbia, I was installed at the far end of a conference table opposite Mrakic Dusan, the state secretary for energy and mines. After an initial back and forth, Dusan interrupted me. “Where are the hard questions?” he demanded. So I asked him if Serbia is inviting unacceptable risks by signing a partnership with Gazprom. “We have a great contract with Russia,” Dusan insisted. I asked him if he worries that Gazprom has an unsound financial and strategic position. “After 2030, only Russia, Qatar, Iran, and Turkmenistan will still have gas. With Russia in control, this ‘gas-OPEC’ will control world supplies.” Dusan rubbed his chin as he spoke, revealing a large fancy watch. I asked where he got it. Smirking, he responded before the translator could finish.

“Putin.”

For the last few years, veteran U.S. diplomat Steven Mann, the State Department’s coordinator for Eurasian energy diplomacy, watched as Americans and Europeans struggled to turn Nabucco from grandiose idea to gas-delivering reality. But when he finally left the job earlier this year, he told author Steve LeVine to beware “Nabucco hucksterism” — a condition he defined as occurring when political enthusiasm for an energy deal gets out too far ahead of its commerical viability. “There have been quite a number of officials who know very little about energy who have been charging into the pipeline debate,” Mann told LeVine. “Nabucco is a highly desirable project, don’t get me wrong. But there are other highly desirable projects besides Nabucco,” he added. “And the overriding question for all these projects is, Where’s the gas?”

For Nabucco to be initially viable, most energy experts agree, the gas will need to come from the former Soviet state of Azerbaijan — 283 billion cubic feet of gas per year, to be precise, roughly 25 percent of the pipeline’s capacity. Indeed, without Azerbaijan and its major natural gas supplies, Nabucco is a non-starter.

Russia knows this too, so it has been doing everything in its power to deny Nabucco gas from Azerbaijan, buying it to replenish Russia’s declining production. In April, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev hosted Azeri President Ilham Aliyev in Moscow to discuss Russian purchases of Azerbaijan’s gas. And then in June, they inked an agreement in which Azerbaijan promised to sell Russia up to 500 million cubic feet of gas — at well over market rate — from its offshore gas field, Shah Deniz.

If there were still any doubt about how far Russia would go to fight for its interests in the Caucasus, Azerbaijan need only look at Georgia, which is still reeling from Russia’s invasion last summer. It is the key transit state between Azerbaijan and Turkey, hosting two pipelines that bring oil and gas from the Caspian to Turkey. By attacking its small neighbor, Russia effectively warned not only Georgia but the whole neighborhood.

But in recent months, Nabucco’s European supporters have started to get their acts together, and Azerbaijan has begun to take notice of that, too. In May, the EU signed a deal of its own with Azerbaijan, which committed to building energy and trade links directly with Europe. This was arguably a more valuable agreement than the one Azerbaijan later signed with Gazprom, which offered not money but only vague pledges that may or may not be met.

Then, on July 13, beneath the crystal chandeliers of an Ankara hotel ballroom, the prime ministers of Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, and Austria signed a Nabucco treaty describing exactly how the pipeline would operate and how tariffs would be calculated. Several days after the announcement that Nabucco had hired Joschka Fischer, who is beloved by many in Turkey for his passionate support for its EU membership, Turkey had dropped a major demand that it had insisted on for months, and the path to the deal was cleared. This was a major breakthrough, and it led Natig Aliyev, Azerbaijan’s energy minister, to remark: “I am sure that the project will be realized successfully.” When that day comes, Azerbaijan will enjoy both higher prices for its gas and a lifeline to the West.

Also in attendance in Ankara was Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki, whose country looks increasingly likely to play a large role in supplying Nabucco — possibly larger than that of Azerbaijan. By some estimates, Iraq could provide more than 500 billion cubic feet of natural gas per year by 2014, when Nabucco is expected to be up and running. All of the major players — Arab Iraqis, Kurdish Iraqis, and the Turks next door — want to see Iraqi gas heading north through Turkey and into Europe. Recently, a Hungarian and an Austrian energy firm, both Nabucco consortium members, made deals to take 10 percent apiece in the $8 billion Pearl Petroleum gas project in Iraqi Kurdistan. It now seems distinctly possible that a pipeline named after Nebuchadnezzar, the ancient ruler of Babylon, might ultimately owe its success to Iraq.

When Gerhard Schröder signed on with Gazprom in 2005, the smart money in the gas war was on Moscow. Now that picture is changing, if slightly. There is a sense that the Kremlin overplayed its hand both in the gas shut-offs to Ukraine and in the Georgia war last summer. Indeed, U.S. Vice President Joe Biden recently echoed this view of Russia’s energy power play. “[Russia’s] actions relative to essentially blackmailing a country and a continent on natural gas, what did it produce?” he pointed out. “You’ve now got an agreement [Nabucco] that no one thought they could have.” At the same time, the global recession has hit Russia particularly hard, and Gazprom’s profits fell 84 percent in the fourth quarter of 2008, making it Russia’s biggest debtor, rather than the world’s biggest company, as it once bragged it would become.

And Nabucco’s European supporters finally seem to be taking their own side in this fight. They now have a heavyweight rainmaker in Fischer, who is going toe to toe with his old boss Schröder in the struggle for influence in the path of the pipelines. The recent EU agreement with Azerbaijan and the fanfare-laden treaty signing in Turkey are contributing to the sense that Europe is leveling the playing field with Russia. “We have started to confound the skeptics, the unbelievers,” European Commission President José Manuel Barroso said in July. “Now that we have an agreement, I believe that this pipeline is inevitable rather than just probable.”

And yet, if recent experience teaches anything, it is not to count Russia out, especially when so much is at stake. When I raised this issue with Russian Energy Minster Sergei Shmatko at a meeting in Bulgaria in April, he shot me a threatening glare and cautioned against planning for an energy future without Russia, unless the Europeans were fully prepared to deliver it. “We have an expression in Russia,” Shmatko told me. “Don’t sell the skin off a bear before you kill it.”