A woman holds a sign reading, “Yesterday Stalin, Today Putin” at a protest in Istanbul against Russian actions in Crimea.

By Glenn Kates

March 09, 2014

ISTANBUL — Serkan Sava’s ancestors left Crimea in a mass exodus some 150 years ago, after the Ottoman Empire staved off Russian pressure in the Crimean War but could not reverse the slow tumble that would lead to its dissolution after World War I.

A century later, the 35-year-old IT consultant’s grandparents, by then rooted in the post-Ottoman Turkish Republic, would hear of Soviet dictator Josef Stalin’s deportation of hundreds of thousands of Crimean Tatars to Central Asia, in 1944, that cost the lives of more than 100,000 people.

This week, Sava stood under a steady rain at a protest of about 250 people — mostly Turkish Crimean Tatars — outside the Russian consulate in Istanbul. Noting that Crimean Tatars “have bad memories” of life under Moscow’s thumb, Sava argued that Turkey should use its influence to ensure that the Black Sea peninsula remains a part of Ukraine and is not annexed by Russia.

With Crimea now occupied by Russian forces, the peninsula’s Russian-majority parliament clamoring to join the Russian Federation, and a referendum on the issue scheduled for March 16, Crimean Tatars are fearful of what another chapter of life under Russian rule could mean.

But if the Crimean Tatar relationship with Russia is rife with tragedy, the Turkish reaction to any potential conflict with Moscow is one of trepidation.

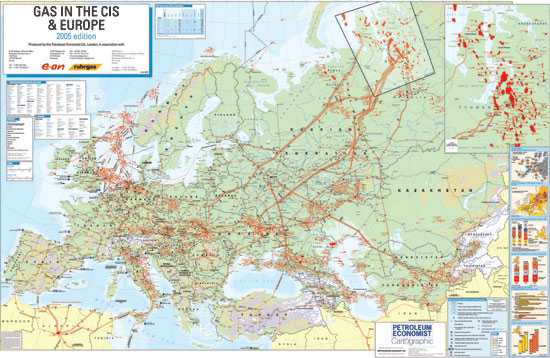

It recalls a past marked by a series of demoralizing military defeats and recognizes a present in which the country enjoys deep trade ties with its Black Sea neighbor, on which it relies for half of its natural-gas supplies.

“Russia is the only neighbor that Turkey really fears for historic and contemporary reasons,” says Soner Cagaptay, author of “The Rise Of Turkey: 21st Century’s First Muslim Power” and director of the Turkish program at the Washington Institute, a U.S.-based think tank. “Historically, there’s a deep-rooted fear among many Turks about not waking up the Russian bear.”

The Crimean Tatars, an ethnic-Turkic people with millions of its diaspora living inside Turkey, would appear to fit in with the role Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan has carved out for himself.

Erdogan, the leader of the Islamist-rooted Justice and Development party (AKP), has spent much political capital casting Ankara as a protector of Muslims along its periphery. Erdogan was a harsh critic of the overthrow of Muslim Brotherhood leader and Egyptian President Muhammad Morsi, and was one of the first world leaders to call for military intervention in Syria against the regime of Bashar al-Assad in the Arab Spring uprising.

Amid the recent political upheaval in Ukraine, Ahmet Davutoglu, Turkey’s foreign minister, was the first envoy to meet with Ukraine’s new government in Kyiv, following months of protests that led to the ouster of the country’s pro-Russian president, Viktor Yanukovych.

With an eye on the past, Erdogan himself has promised not to “leave Crimean Tatars in the lurch.”

But Erdogan, who has appeared at times to relish conflict with other world leaders, has carefully nurtured his relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin and appears unlikely to stake out a position that would put Ankara-Moscow ties at serious risk.

“If you look at Erdogan’s mercurial political style, he has pretty much yelled at every and any head of government he has dealt with with the exception of the Russian and the Iranian president,” Cagaptay says, “not because he likes them necessarily but because Turkey gets about three-quarters of its gas and oil from Iran and Russia.”

Ottoman-Russian history is also a factor, says Cagaptay, who wrote in a recent paper that, over a period of almost 400 years, the Ottoman Empire fought in at least 17 wars with Russia and lost all of them.

Further complicating matters is that the 1936 Montreaux treaty, which gives Turkey control over the straits that link the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, also limits the weight of warships that would be allowed to pass through from states not located on the Black Sea.

Any adaptation of this restriction by Turkey in favor of its NATO partners would put the treaty at risk.

But as Celal Icten, the president of the Istanbul branch of Turkey’s Crimea Tatar Association, points out, it may be that the current domestic political climate provides the main hindrance to a greater role by Ankara in helping resolve the crisis in Ukraine.

Erdogan, who has been embroiled in a months-long corruption scandal, is fighting for his political career, and municipal elections at the end of March are seen as a barometer of the remaining strength of his ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP).

Icten says Erdogan and President Abdullah Gul are doing all they can, given the circumstances.

“Turkey’s current political climate is hectic and that’s why the president and prime minister’s support for Crimean Tatars gets lost among other things on the political agenda,” Icten says. “But [they’ve] given support to Crimean Tatars and continue cooperation with Western powers in Europe.”

Cagaptay agrees that Ankara will cooperate with Europe, which has proposed limited sanctions, but is unlikely to take a leading role unless serious violence is inflicted on the Crimean Tatar population.

That might not assuage Crimean Tatars like Sava, who say the protection of a Turkic minority that is under threat should outweigh any political concerns.

While Moscow refuses to recognize Ukraine’s new government because it is led by “fascists” who pose a threat to ethnic Russians, Tatars in Crimea — some of whose homes have reportedly been marked with an ominous “X”– say they are being singled out by Russian “self-defense” brigades.

At the Istanbul demonstration, protesters chanted, “Turkey, help your brothers!” and, “We are shoulder-to-shoulder against the enemy!”

Erugrul Toksoy, a 47-year-old account manager sporting a blue scarf with the Crimean Tatar insignia, says Erdogan “has done nothing” to help Crimean Tatars, who make up 12 percent of the peninsula’s population.

Sava, the IT consultant, riffing on a quote from the late British statesman Winston Churchill about the dangers of appeasement, warns that waiting for action will have its own costs.

“The one who tries to protect the current state [of affairs] is hopeful that the crocodile will eat him last,” Sava says.