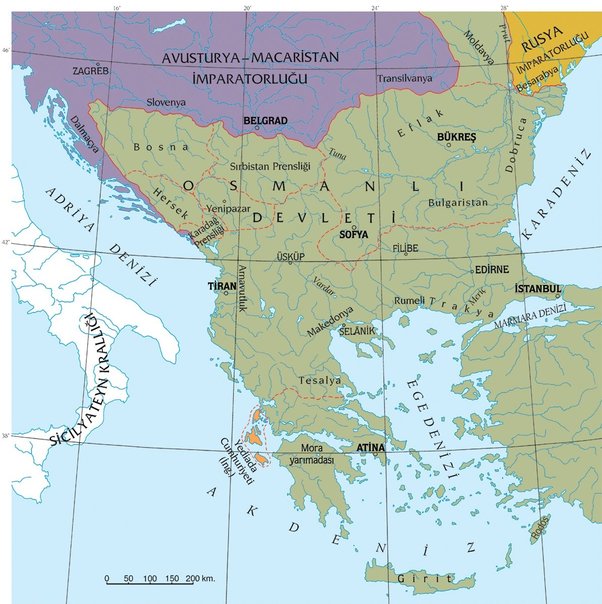

The Balkans is a southeastern European region that includes countries located on the Balkan Peninsula, with diverse landscapes and climates:

Albania, Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Greece, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, Turkey

Countries in the Balkans often share borders with one another, and historical border disputes have influenced regional dynamics. Many Balkan nations were once part of the Ottoman Empire, which has left a significant historical and cultural impact.

The breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s resulted in violent conflicts, with lasting implications for the region.

The Balkans are home to various ethnic groups and religions, with Orthodox Christianity, Islam, and Catholicism being the major faiths.

Some Balkan nations aspire to join the European Union and NATO, which has implications for their political and economic development; while others have already become members.

Let’s compare them by several key attributes relating to their military, size, economy and quality of life.

We will look at the top 3 and bottom 3 in each case.

Military power (Global Fire Power index – 2023) 0 = Super military power and higher the number= less military power

Top 3

- Turkey (11th in the world) – 0.2016

- Greece (30th in the world) – 0.4621

- Romania (47th in the world) – 0.7735

Bottom 3

- Bosnia and Herzegovina (133rd in the world) – 3.0788

- Montenegro (128th in the world) – 2.8704

- North Macedonia (108th in the world) – 2.1717

Population

Top 3

- Turkey – 84.78 million (2021)

- Romania- 19.12 million (2021)

- Greece – 10.64 million (2021)

Bottom 3

- Montenegro – 619, 211 (2021)

- North Macedonia- 2.065 million (2021)

- Slovenia- 2.108 million (2021)

Landmass

Top 3

- Turkey – 783, 562 km²

- Romania – 238, 397 km²

- Greece – 131, 957 km²

Bottom 3

- Montenegro – 13, 812 km²

- Slovenia – 20, 273 km²

- North Macedonia – 25, 713 km²

Education (UN education index – measures the expected years of schooling and mean years of schooling of the population – 0 = no Education at all and 1 = maximum Education)

Top 3

- Slovenia – 0.914 (2019)

- Greece – 0.855 (2019)

- Croatia – 0.805 (2019)

Bottom 3

- North Macedonia 0.704 (2019)

- Bosnia and Herzegovina 0.711 (2019)

- Turkey 0.731 (2019)

Democracy Index (The Economists Intelligence Unit – 2022, 10 = super democratic and 0 = dictatorship)

Top 3

- Greece – 7.97, Flawed Democracy (25th in the world)

- Slovenia – 7.75, Flawed Democracy (31st in the world)

- Bulgaria – 6.53, Flawed Democracy (57th in the world)

Bottom 3

- Turkey – 4.35, Hybrid regime (103rd in the world)

- Bosnia and Herzegovina – 5.00, Hybrid regime (97th in the world)

- North Macedonia – 6.10, Flawed Democracy (72nd in the world)

GDP (size of economy)

Top 3

- Turkey – $819 billion (2021)

- Romania – $284.1 billion (2021)

- Greece – $214.9 billion (2021)

Bottom 3

- Montenegro – $5.861 billion (2021)

- North Macedonia – $13.83 billion (2021)

- Albania – $18.26 billion (2021)

GDP per capita (size of economy relative to population)

Top 3

- Slovenia – $29, 291.40 (2021)

- Greece – $20,192.60 (2021)

- Croatia – $17,685.33 (2021)

Bottom 3

- Albania – $6,492.87 (2021)

- North Macedonia – $6,694.64 (2021)

- Bosnia and Herzegovina- $7,143.31 (2021)

GDP per capita at Purchasing Power Parity – IMF (how much can people buy with money in a country)

Top 3 (2023)

- Slovenia – $52,641

- Croatia – $42,531

- Romania – $41,634

Bottom 3 (2023)

- Albania – $19,197

- Bosnia and Herzegovina – $19,604

- North Macedonia – $21,111

Exports of goods and services (in millions of $, 2022)

Top 3

- Turkey – 343,688

- Romania – 129,165

- Greece – 105,756

Bottom 3

- Montenegro -3,178

- Albania – 7,057

- North Macedonia – 10,150

Percentage of Population Living in Poverty – Poverty Rate, World Bank

Top 3 (with lowest poverty of population)

- Slovenia – 12% (2018)

- Albania – 14.3% (2012)

- Bosnia and Herzegovina – 16.9% (2018)

Bottom 3 (with highest poverty of population)

- Montenegro – 24.5% (2018)

- Bulgaria tied with Romania – 23.8% (2018)

- Serbia – 23.2% (2018)

Peacefulness (Global Peace Index 2023, 1 – 5 scale, 1 being a super peaceful utopia and 5 being a warzone)

Top 3

- Slovenia – 1.334 (8th in the world)

- Croatia – 1.450 (14th in the world)

- Bulgaria – 1.640 (30th in the world)

Bottom 3

- Turkey – 2.389 (121st in the world)

- North Macedonia – 2.039 (88th in the world)

- Albania – 1.925 (79th in the world)

Happiness (Happiness Index, 2023, 10 being maximum happiness and 0 being totally depressed)

Top 3

- Slovenia – 6.63 (22nd in the world)

- Romania – 6.48 (27th in the world)

- Serbia- 6.18 (43rd in the world)

Bottom 3

- Turkey – 4.74 (109th in the world)

- Albania – 5.2 (88th in the world)

- Bulgaria – 5.37 (84th in the world)

Suicide Rate (suicides per 100,000, WHO, 2019)

Top 3 (has the least suicide)

- Turkey – 2.3 (10th in the world)

- Greece – 3.6 (27th in the world)

- Albania – 3.7 (29th in the world)

Bottom 3 (has the most suicide)

- Montenegro – 16.2 (161st in the world)

- Slovenia – 14 (150th in the world)

- Croatia – 11 (121st in the world)

Homicide rate (murders per 100,000, UN)

Top 3 (with least murders)

- Slovenia – 0.4 (2021)

- Greece – 0.9 (2021)

- Bosnia and Herzegovina – 1 (2021)

Bottom 3 (with most murders)

- Turkey – 2.5 (2021)

- Montenegro – 2.4 (2021)

- Albania – 2.3 (2021)

Healthcare Index (100 being amazing quality & universal healthcare and 0 being 0 healthcare, 2023)

Top 3

- Turkey – 71.1

- Slovenia – 66.4

- Croatia – 64.5

Bottom 3

- Albania – 49.3

- Serbia – 52.2

- Bosnia and Herzegovina -54.8

Life expectancy

Top 3

- Slovenia – 82.31 Years

- Greece – 82 Years

- Croatia – 79.4 Years

Bottom 3

- Bulgaria – 72.84 Years

- Romania – 75.14 Years

- Serbia – 75.21 Years

CONCLUSION:

Turkey has the most economic and military power as a whole, due primarily to it’s size.