MOSCOW. (RIA Novosti political commentator Dmitry Kosyrev) – The ongoing ethnic riots in Urumqi, China, can threaten other countries, in particular the United States and Russia.

The growth of Uyghur terrorism can complicate Barack Obama’s anti-terrorism policy focused on Afghanistan and Pakistan and affect Russia’s policy in Central Asia.

Since life itself is forcing Russia and the U.S. to cooperate in Central Asia and Afghanistan, we can presume that President Dmitry Medvedev and President Barack Obama wish the Chinese authorities success in restoring order in Urumqi.

Riots broke out in Urumqi, capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur province in northwest China, on July 5. They were organized by Uyghurs and were foreseen to claim lives.

First, the reason for the riots was the killing of two Uyghurs, most likely by the police, in Shaoguan in southern China, on June 25 during demonstrations provoked by government handling of a conflict between Han Chinese and Uyghur factory workers.

Ten days later, several hundred Uyghurs, most of them peaceful people, held a demonstration in Urumqi. At the same time, their much less peaceful compatriots started burning and smashing vehicles and confronting security forces.

Second, I cannot imagine anyone setting fire to a shop with a lighter. You need at least a canister of gasoline to do that. It reminded me about the anti-Chinese riots in Lhasa, Tibet, in March 2008. In both cases, there were trained provocateurs inciting the public.

Another factor proving my point is the reported number of the dead, over 140 as of Monday. There are never so many dead during ordinary, spontaneous street unrest.

Like Tibetans, Uyghurs are an ethnic minority with a powerful foreign diaspora. The Uyghur diaspora is known for its terrorist groups, which have staged more than one terrorist attack in China’s main cities other than in Xinjiang.

The Chinese authorities may have pointed to the rioters’ links with these groups too soon, but they could logically presume such connection as all previous riots were proved to be connected to the diaspora.

There are many possible links apart from the U.S.-based World Uyghur Congress (WUC).

Until recently, one of such links could lead to Kyrgyzstan, which has a large Uyghur population. It is for that reason that in the 1990s China focused on a project that has since become known as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

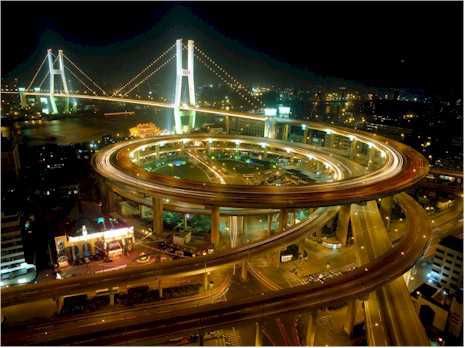

People from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and other neighboring countries routinely go to Urumqi for their purchases, medical assistance, and recreation. Urumqi is a trade and business center of a booming economic zone, which incorporates all Central Asian people and their West Chinese colleagues.

For this reason, we need not worry that the terrorist groups made up of Chinese minorities will receive assistance from Central Asia. However, it transpired in the 1980s that Uyghur terrorists were connected with subversives in Afghanistan and Pakistan. So, theoretically, Uyghurs, who are Muslims, are one of the problems facing Obama and Medvedev.

Like many other similar organizations operating in the United States or any other country, Uyghurs are financed by American NGOs. This is an element of the U.S. policy that has failed, even though the new administration has not yet officially disavowed it.

Besides, leaving such organizations to their own devices could be dangerous, as proved by the example of Al Qaeda.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily represent those of RIA Novosti.

The civilisation state

The civilisation state