Chinese propaganda obscures what sparked Sunday’s riots.

By REBIYA KADEER

By REBIYA KADEER

When the Chinese government, with the comfort of hindsight, looks back on its handling of the unrest in Urumqi and East Turkestan this week, it will most likely tell the world with great satisfaction that it acted in the interests of maintaining stability. What officials in Beijing and Urumqi will most likely forget to tell the world is the reason why thousands of Uighurs risked everything to speak out against injustice, and the fact that hundreds of Uighurs are now dead for exercising their right to protest.

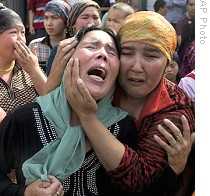

On Sunday, students organized a protest in the Döng Körük (Erdaoqiao) area of Urumqi. They wished to express discontent with the Chinese authorities’ inaction on the mob killing and beating of Uighurs at a toy factory in Shaoguan in China’s southern Guangdong province and to express sympathy with the families of those killed and injured. What started as a peaceful assembly of Uighurs turned violent as some elements of the crowd reacted to heavy-handed policing. I unequivocally condemn the use of violence by Uighurs during the demonstration as much as I do China’s use of excessive force against protestors.

While the incident in Shaoguan upset Uighurs, it was the Chinese government’s inaction over the racially motivated killings that compelled Uighurs to show their dissatisfaction on the streets of Urumqi. Wang Lequan, the Party Secretary of the “Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region” has blamed me for the unrest; however, years of Chinese repression of Uighurs topped by a confirmation that Chinese officials have no interest in observing the rule of law when Uighurs are concerned is the cause of the current Uighur discontent.

China’s heavy-handed reaction to Sunday’s protest will only reinforce these views. Uighur sources within East Turkestan say that 400 Uighurs in Urumqi have died as a result of police shootings and beatings. There is no accurate figure for the number of injured. A curfew has been imposed, telephone lines are down and the city remains tense. Uighurs have contacted me to report that the Chinese authorities are in the process of conducting a house-to-house search of Uighur homes and are arresting male Uighurs. They say that Uighurs are afraid to walk the streets in the capital of their homeland.

The unrest is spreading. The cities of Kashgar, Yarkand, Aksu, Khotan and Karamay may have also seen unrest, though it’s hard to tell, given China’s state-run propanganda. Kashgar has been the worst effected of these cities and unconfirmed reports state that over 100 Uighurs have been killed there. Troops have entered Kashgar, and sources in the city say that two Chinese soldiers have been posted to each Uighur house.

The nature of recent Uighur repression has taken on a racial tone. The Chinese government is well-known for encouraging a nationalistic streak among Han Chinese as it seeks to replace the bankrupt communist ideology it used to promote. This nationalism was clearly in evidence as the Han Chinese mob attacked Uighur workers in Shaoguan, and it seems that the Chinese government is now content to let some of its citizens carry out its repression of Uighurs on its behalf.

This encouragement of a reactionary nationalism among Han Chinese makes the path forward very difficult. The World Uighur Congress that I head, much like the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan movement, advocates for the peaceful establishment of self-determination with genuine respect for human rights and democracy. To achieve this objective, there needs to be a path for Han Chinese and Uighur to achieve a dialogue based on trust, mutual respect and equality. Under present Chinese government policies encouraging unchecked nationalism, this is not possible.

To rectify the deteriorating situation in East Turkestan, the Chinese government must first properly investigate the Shaoguan killings and bring those responsible for the killing of Uighurs to justice. An independent and open inquiry into the Urumqi unrest also needs to be conducted so that Han Chinese and Uighurs can understand the reasons for Sunday’s events and seek ways to establish the mutual understanding so conspicuously absent in the current climate.

The United States has a key role to play in this process. Given the Chinese government’s track record of egregious human-rights abuses against Uighurs, it seems unlikely Beijing will drop its rhetoric and invite Uighurs to discuss concerns. The U.S. has always spoken out on behalf of the oppressed; this is why they have been the leaders in presenting the Uighur case to the Chinese government. The U.S., at this critical juncture in the East Turkestan issue, must unequivocally show its concern by first condemning the violence in Urumqi, and second, by establishing a consulate in Urumqi to not only act as a beacon of freedom in an environment of fierce repression but also to monitor the daily human-rights abuses perpetrated against the Uighurs.

As I write this piece, reports are reaching our office in Washington that on Monday, 4,000 Han Chinese took to the streets in Urumqi seeking revenge by carrying out acts of violence against Uighurs. On Tuesday, more Han Chinese took to the streets. As the violence escalates, so does the pain I feel for the loss of all innocent lives. I fear the Chinese government will not experience this pain as it reports on its version of events in Urumqi, and it is this lack of self-examination that further divides Han Chinese and Uighurs.

Ms. Kadeer is the president of the Uighur American Association and World Uighur Congress.

The Wall Street Journal

Baku – APA. Turkish Prime Minister Racab Tayyib Erdogan took stance on bloody events taking place in Xinjiang-Uighur autonomous region of China, APA reports quoting Haberturk.

Baku – APA. Turkish Prime Minister Racab Tayyib Erdogan took stance on bloody events taking place in Xinjiang-Uighur autonomous region of China, APA reports quoting Haberturk.