If Kyrgyz-style violence should radiate across borders in Central Asia, the result could be a rise in Islamic militancy that would directly threaten Russia and the United States.

Diplomatic Memo

Value to Big Powers May Not Save Kyrgyzstan

Bryan Denton for The New York Times

Roza Otunbayeva, the head of the provisional government in Kyrgyzstan, landing by helicopter in the southern city of Osh on Friday, after days of ethnic fighting there.

By ELLEN BARRY

Published: June 18, 2010

MOSCOW — A year and a half ago, the world’s great powers were fighting like polecats over Kyrgyzstan, a landlocked stretch of mountains in the heart of Central Asia.

Related

-

Some Refugees Begin Returning to Kyrgyzstan (June 19, 2010)

-

Times Topic: Kyrgyzstan

The United States was ferociously holding on to the Manas Air Base, a transit hub considered crucial to NATO efforts in Afghanistan.

Russia was so jealous of its traditional dominance in the region that it promised the Kyrgyz president $2.15 billion in aid the day he announced he was closing Manas. With the bidding war that followed, Kyrgyzstan could be forgiven for seeing itself as a global player.

And yet for the past week, as spasms of violence threatened to break Kyrgyzstan apart, its citizens saw their hopes for an international intervention flicker and die. With each day it has become clearer that none of Kyrgyzstan’s powerful allies —

most pointedly, its former overlords in Moscow — were prepared to get involved in a quagmire.

Russia did send in several hundred paratroopers, but only to defend its air base at Kant. For the most part, the powers have evacuated their citizens, apparently content to wait for the conflict to burn itself out.

The calculus was a pragmatic one, made “without the smallest thought to the moral side of the question,” said Aleksei V. Vlasov, an expert in the politics of post-Soviet countries at Moscow State University.

“We use the phrase ‘collective responsibility,’ but in fact this is a case of collective irresponsibility,” he added. “While they were fighting about whatever — about bases, about Afghanistan — they forgot that in the south of Kyrgyzstan there was extreme danger. The city was flammable. All they needed to do was throw a match on it.” He referred to the city of Osh, which suffered days of ethnic rioting.

Kyrgyzstan might have unraveled anyway, but competition between Moscow and Washington certainly sped the process.

To lock in its claim on the base after the threat of expulsion, the United States offered President

Kurmanbek S. Bakiyev $110 million to back out of his agreement with Russia, which had already paid him $450 million. Congratulating itself on its victory, Washington raised the stakes by announcing the construction of several military training facilities in Kyrgyzstan, including one in the south, which further irritated Moscow.

This spring, the Kremlin won back its lost ground, employing a range of soft-power tactics to undermine Mr. Bakiyev’s government. Mr. Bakiyev was ousted by a coalition of opposition leaders in April, and conditions in Kyrgyzstan’s south — still loyal to the old government — hurtled toward disaster.

“Let’s be honest, Kyrgyzstan is turning into a collapsing state, or at least part of it is, and what was partially responsible is this geopolitical tug of war we had,” said Alexander A. Cooley, who included Manas in a recent book about the politics of military bases. “In our attempts to secure these levers of influence and support the governing regime, we destabilized these state institutions. We are part of that dynamic.”

Last week, as pillars of smoke rose off Osh and Jalal-Abad, citizens begged for third-party peacekeepers to replace local forces

they suspected of having taken part in the violence.

Roza Otunbayeva, the head of Kyrgyzstan’s interim government, asked Moscow for peacekeepers, and when that request was denied, for troops to protect strategic sites like power plants and reservoirs. She asked Washington to contribute armored vehicles from the base at Manas, which she said would be used to transport the dead and wounded, she told the Russian newspaper Kommersant.

So far, Moscow and Washington have responded mostly with humanitarian aid pledges — late on Friday, Russia’s Defense Ministry said that Ms. Otunbayeva’s request was still under consideration.

The United States, overextended in Afghanistan and Iraq, has neither the appetite nor the motivation for a new commitment. Russia, the more obvious player, sees the risks of a deployment outweighing the benefits. Russian troops would enter hostile territory in south Kyrgyzstan, where Mr. Bakiyev’s supporters blame Moscow for his overthrow, and Uzbekistan could also revolt against a Russian presence.

Mr. Vlasov, of Moscow State University, said: “Who are we separating? Uzbeks from Kyrgyz? Krygyz from Kyrgyz? Kyrgyz from some criminal element? There is no clearly defined cause of this conflict. It would be comparable to the decision the Soviet Politburo made to invade Afghanistan — badly thought through, not confirmed by the necessary analytical work.”

If the explosion of violence was a test case for the Collective Security Treaty Organization, an eight-year-old post-Soviet security group dominated by Russia, it seems to have failed, its leaders unwilling to intervene in a domestic standoff. In any case, neither the Russian public nor the county’s foreign policy establishment is pressing the Kremlin to risk sending peacekeepers.

“If you send them, you have to shoot sooner or later,” said Sergei A. Karaganov, a prominent political scientist in Moscow. “Then you are not a peacekeeper, but something else.”

Though it seems that the worst of the violence has passed, great challenges remain. Beyond the immediate humanitarian crisis is an unstable state at the heart of a dangerous region. The Ferghana Valley, bordering Afghanistan, is a minefield of religious fundamentalism, drug trafficking and ethnic hatreds.

If Kyrgyz-style violence should radiate across borders in Central Asia, the result could be a rise in Islamic militancy that would directly threaten Russia and the United States.

The failure of international institutions last week should alarm both capitals. President Obama and President Dmitri A. Medvedev of Russia began their relationship with the crisis over the Manas base, and as they grope toward tentative collaboration in the post-Soviet space, Kyrgyzstan has dominated their conversation.

Now, Kyrgyzstan needs help building a stable government that

knits together the north and the south. Dmitri V. Trenin, director of the Carnegie Moscow Center, suggested that NATO should be working with the members of the Collective Security Treaty Organization to develop a mechanism for collective action. The next time a Central Asian country is wobbling at the edge of a precipice, he said, someone must be prepared to accept responsibility.

“You can abstain from a local conflict in Kyrgyzstan,” Mr. Trenin said. “You can close your eyes to it — it’s bad for your conscience — but you can live with it. If something happens in Uzbekistan, you will not be able to just let it burn out.”

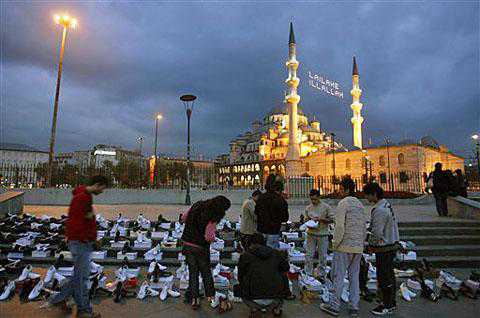

The Uzbek parliament building in Tashkent (file photo)

The Uzbek parliament building in Tashkent (file photo)