Chiquita Papers : Uncertainty Fueled Staff Concerns about Payments to Guerrillas and Paramilitaries

Colombia Payments a “Leap of Faith”

“We are funding their activities, or we are protecting ourselves. It’s questionable.”

CFO asks: “How can I audit that? I cannot ask them to sign a receipt.”

Posted May 2, 2017

National Security Archive Briefing Book No. 589

Edited by Michael Evans

For further information, contact: mevansTwitter: @colombiadocs

Washington, D.C., May 2, 2017 – Chiquita’s Colombia-based staff questioned the company’s payments to illegal armed groups, and asked whether Chiquita had gone beyond extortion and was directly funding the activities of leftist guerrillas and right-wing paramilitary groups, even while top company executives became “comfortable” with the idea.

This is the second in a series of stories jointly published by the National Security Archive and VerdadAbierta.com documenting how the world’s most famous banana company financed terrorist groups in Colombia.

The New Chiquita Papers are the result of a seven-year legal battle waged by the National Security Archive against the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, and later Chiquita itself, for access to tens of thousands of records produced by the company during an investigation of illicit payments made in Colombia.

The Archive has used these records to identify individual Chiquita executives who approved and oversaw years of payments to groups responsible for countless human rights violations in Colombia, but whose roles in the affair have been unknown or unclear until now.

In this installment, we examine the roles of financial officers, security staff and hired intermediaries on the ground in Colombia who managed an unorthodox payments process one official described as a “leap of faith.”

The following article was also published today in Spanish at VerdadAbierta.com.

* * *

Payments to Armed Groups Generated Internal Conflicts at Chiquita Brands

The banana company invented an accounting system to hide payments to guerrilla groups in Colombia that they admitted were “impossible to audit.” Even while senior Chiquita officials became “comfortable” with the way the payments were made, officials based in Colombia had their reservations.

By Tatiana Navarrete and Juan Diego Restrepo E.

Edited by Michael Evans – This is the second in a series of articles published jointly by the National Security Archive and VerdadAbierta.com

“[These] were payments that, you know, are questionable, payments to the guerrillas that at the end are payments that, you know, are questionable,” said Jorge Forton, chief financial officer for Banadex, Chiquita’s wholly-owned subsidiary in Colombia, in his April 27, 1999 statement to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). “We are funding their activities, or we are protecting ourselves. It’s questionable.”[1]

The deposition of this Peruvian accountant, who worked for Chiquita from 1990-1998, turns out to be key evidence on a little-known chapter in the history of Colombia’s banana-growing zone: payments made by the multinational fruit company to anti-government guerrilla groups like the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the National Liberation Army (ELN), and the Popular Liberation Army (EPL), and the funding of political organizations like the Current for Socialist Renovation (CRS), Hope, Peace and Liberty, and the Popular Commands.

Forton began in 1990 at Chiquita headquarters in Cincinnati, Ohio, looking for opportunities to expand the company’s worldwide operations. In the middle of 1994, he was sent to Colombia to assess how the local economy was affecting the prices of banana production. Over the next few months, Forton returned to the country several times and proposed alternatives for reorganizing Colombian operations. At the end of the year, Forton accepted a new position as chief financial officer for Banadex in Medellín.

Since his arrival in Colombia in early 1995, the accountant knew that Chiquita made “sensitive payments” to illegal armed groups to ensure, as he was told, that its workers were not killed or kidnapped and that its plantations were not burned to the ground. “My role was to see how we could standardize and have a good control of those payments,” he said to the SEC.

At that time, there were two Chiquita offices in Colombia: Banadex, in Medellín, and Samarex, in Santa Marta; each with independent accounting systems and separate sets of books to record payments not only to guerrillas but to the Colombian Armed Forces, which also benefitted from the company’s secret security fund. Forton’s job was to unify the accounts so Cincinnati could better track the payments. The company asked him to prepare a report on all the “sensitive payments” realized since 1992, something that, according to Forton, was almost impossible given the “poor accounting records” that had existed up to that point.

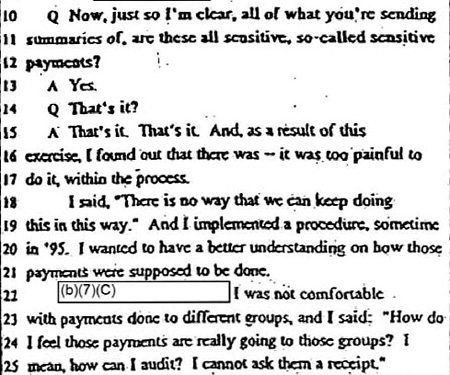

SEC Testimony of Jorge Forton, April 27, 1999, pp. 45-46.

So Forton implemented a new procedure to better account for the payments. He introduced two basic rules: there would be no more cash payments, and none would be authorized without an invoice.

Forton said he was “not comfortable” with the guerilla payments: “How do I feel those payments are really going to those groups? I mean, how can I audit that? I cannot ask them to sign a receipt.”

The fact that Colombian guerrilla groups could not be counted on to provide receipts elevated the role of the Security Department and the intermediaries they relied on as go-betweens with the insurgent factions, military units, and paramilitary groups at the receiving end of those payments. These are the names and signatures that appear on the forms used to request payments to the various armed groups.

The fewer people who knew about the “sensitive payments,” the better, so the payments only needed the authorization of the general manager, Charles Keiser, and the signature of Forton. Keiser was followed as general manager by Álvaro Acevedo, who later oversaw several years of payments to the paramilitary United Self-defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) and today works for a fruit producer in Ecuador. VerdadAbierta.com tried to contact Acevedo, but did not receive a response.

Forton instituted the “1016” form to register all of the payments and to camouflage them among the fruit multinational many other expenses. To do so, he created two new accounts: “Logistics,” for payments to government agencies; and “Operations” for payments to guerrilla groups.

This rigorous accounting system coldly recorded the harsh reality of life in the violently-contested region of Urabá during the 1990s. Forton was aware of the impact that the payments had on public order and thought it indispensable to know whether the money found its way to the intended recipients. At the very least, the ultimate destination of the payments mattered more to Forton than to his superiors in Cincinnati, who had not witnessed Colombia’s war in person.

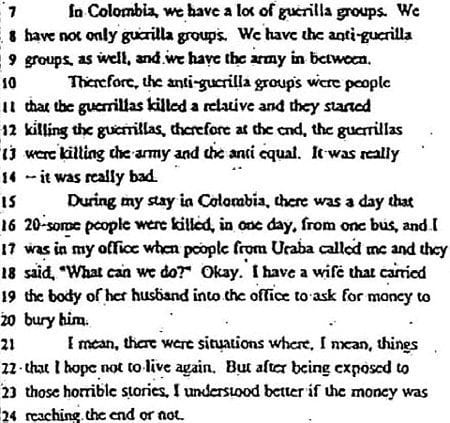

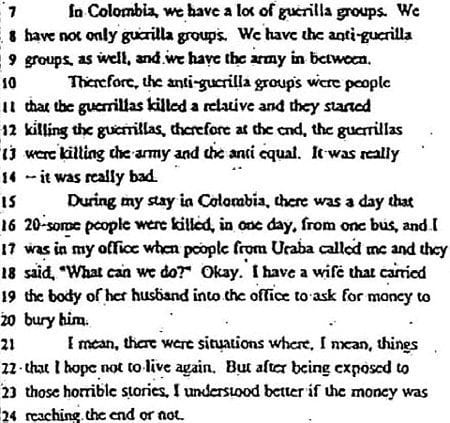

In a vivid account to the SEC, Forton said the surge in paramilitary groups (or “anti-guerrilla groups,” as he called them)—who were also financed by the company—had intensified conflict in the region. He recalled a day when some 20 bus riders were killed, and a subsequent call from company staff in Urabá asking what to do. “I have a wife that carried the body of her husband into the office to ask for money to bury him,” he remembered.

SEC Testimony of Jorge Forton, April 27, 1999, p. 57.

“There were situations where, I mean, things that I hope not to live again. But after being exposed to those horrible stories, I understood better if the money was reaching the end or not,” he explained.

Forton left Colombia in 1996 and was effectively fired from the company in 1998 for his role in authorizing bribes to Colombian port authorities in Turbo, Antioquia. Forton is now a high-ranking official at Dun & Bradstreet, according to his LinkedIn account. VerdadAbierta.com did not receive a response from a message sent to Forton through the social media network.

Where did the money actually go?

The names of the individuals from the Security Department who handled the “sensitive payments” to armed groups in Colombia during that time, Juan Manuel Alvarado and John Stabler, are found in a draft Chiquita legal memorandum dated January 5, 1994.

One of the chief intermediaries used as a bridge between the company and the insurgent groups was René Alejandro Osorio J., an attorney from Antioquia who in 1992 signed a services contract with the Compañía Frutera de Sevilla, another of Chiquita’s Colombian subsidiaries.

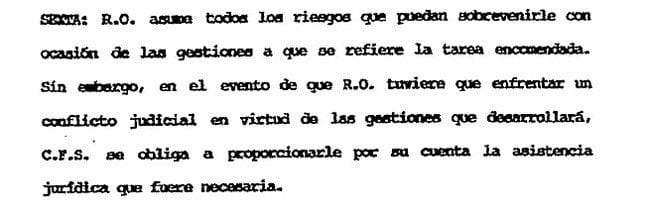

His role as a “Security Consultant” for Chiquita is revealed in an earlier draft of the same memo, dated January 4, 1994, which identifies Osorio as the company’s “contact with the various guerrilla groups in both Divisions.” The professional middleman was responsible for making “guerrilla extortion payments” for Chiquita. In many internal company records, he is referred to by the initials “R.O.”

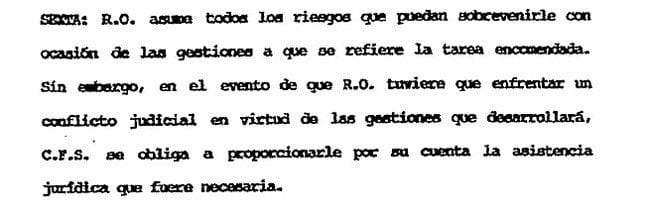

Another document obtained by the National Security Archive is a copy of a contract signed by Osorio indicating that he was paid five million Colombian Pesos (about five thousand U.S. dollars) every three months. Osorio assumed all risks involved with the assigned work, but Chiquita would provide legal assistance if it ever became necessary. VerdadAbierta.com contacted him in Medellin, where he apparently resides, to hear his version, but made clear that he "was not going to refer to that subject".

The sort of informality that existed between Chiquita Brands and the intermediaries made it even more difficult to determine if the money was actually reaching the guerrillas and generated suspicions among some of the managers in Medellín.

Even when the payments were made in cash, before the arrival of Forton as CFO, it was never really known whether they arrived in their totality to the guerrillas. John Ordman, based in Costa Rica, was a key link between Chiquita’s Colombian operations and top executives at the company’s headquarters in Cincinnati (as explained in the first article in this series). Ordman called these payments "a leap of faith."

“Now does it get distributed to the people that it should be? Does it get distributed – you know, there’s a commission for this guy [name redacted]. Does he take half of it and put it in his pocket? How do you tell? There’s no way of determining that.”

SEC Testimony of John Ordman, November 23, 1999, pp. 124-125.

In spite of this, Ordman said he felt “comfortable that this was being handled in a responsible way.” The view of Robert F. Kistinger, head of Chiquita’s Banana Group, was much the same. He told the SEC he saw the guerrilla payments as an “ongoing cost” of company operations, like the purchase of fertilizers or agrichemicals.

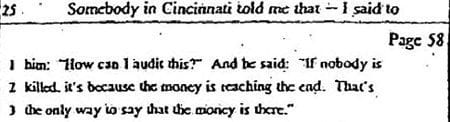

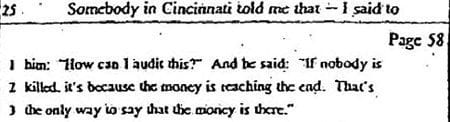

Forton told the SEC that he took the concerns about his inability to track the payments to a top executive in Cincinnati, asking, “How can I audit this?” And the response was: “If nobody is killed, it’s because the money is reaching the end. That’s the only way to say that the money is there.”

SEC Testimony of Jorge Forton, April 27, 1999, p. 58.

The person who provided that response may well have been Robert Kistinger, since SEC investigators asked him about this same episode during his interview, but denied ever having such a conversation with Forton.

SEC Testimony of Robert Kistinger, January 6, 2000, pp. 66-67.

Forton was not the only person who worried that the money could not be tracked. His replacement in Colombia, John Paul Olivo, who arrived in 1996, voiced similar concerns in his SEC testimony. Olivo’s name has been known to Colombian investigators since 2009 when the Attorney General opened an investigation against him and two other officials, Charles Keiser and Dorn Wenninger, for conspiracy to commit an aggravated felony—a process that has gone nowhere in eight years.

In his December 1999 testimony to the SEC, Olivo said he did not feel comfortable with the way the company made the payments, since it was impossible to know whether Alvarado, Osorio and the others were actually delivering the money to the armed groups. “The only person that requests funds and payments for guerrillas is the head of security,” he said. “No one ever knows who – or negotiates with this groups, except for himself. And that’s been my . . . concern since day one.”

SEC Testimony of John Paul Olivo, December 15, 1999, p. 64.

More than extortion?

In his declaration, Kistinger said the company made the payments because they were being extorted and wanted to protect the lives of their workers amid constant threats. For this reason, Chiquita also paid Colombian military and police forces, above all when they needed special security services.

While the internal discussions of Chiquita employees mostly revolved around the technical aspects of the payments, Forton’s deposition is testament to the thin line between paying extortion and willingly funding the operations of a violent group.

SEC Testimony of Jorge Forton, April 27, 1999, pp. 90-91.

Other documents obtained by the National Security Archive indicate that Chiquita’s outlays to guerrillas were perhaps not as innocent as the company portrayed them in negotiations with Colombian and U.S. authorities. As the following draft legal memorandum demonstrates, at least some Chiquita officials believed the payments were illegal under Colombian law, while others wanted to eliminate evidence of such knowledge from the record.

The same memo also suggests that not all of the payments were the result of extortion. If indeed the multinational made the payments to protect itself from guerrilla threats, it is equally clear that some of Chiquita’s farms were supplied with “security personnel” from “Guerrilla Groups.”

Why did Chiquita Brands make payments to virtually every guerrilla group in Urabá? How much did the FARC, ELN, EPL and the other groups receive each year, according to company records? Were there any contracts or agreements with insurgent groups?

The complex relationship between Chiquita Brands and Colombian guerrillas will be the subject of the next report in this series, to be published next Tuesday by the National Security Archive and VerdadAbierta.com.

- The depositions of the seven Chiquita employees interviewed by the SEC were obtained by the National Security Archive after seven years of litigation. Although the names of those officials remained hidden, it was possible to identify them by comparing the transcripts to other official sources.

READ THE DOCUMENTS

Document 01

1992-12-14

[Bill for Services Rendered]

Source: Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

Bill for services rendered to Compañia Frutera de Sevilla on letterhead of "Rene Alejandro Osorio J."

Document 02

1992-12-18

["Contract for Provision of Professional Services"] [Includes original attachment]

Source: Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

Copy of a contract between a Chiquita subsidiary and Rene Osorio, identified by the initials "R.O." The attached forms indicate that the three million Peso payment was to a "security advisor" who "works as liaison with activist groups."

Document 03

1994-01-04

"Reportable Payments in Colombia and Manager’s Expense Payments" [Draft; includes original annotations

<

p class=”MsoNormal”>Source: Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

<

p class=”MsoNormal”>

<

p class=”MsoNormal”>Draft Chiquita legal memorandum on payments to guerrilla groups in Colombia identifies intermediary employed by Security Department to handle payments to guerrilla groups.

<

p class=”MsoNormal”>

<

p class=”MsoNormal”>Document 04

<

p class=”MsoNormal”>

<

p class=”MsoNormal”>1994-01-05

<

p class=”MsoNormal”>"Reportable Payments in Colombia and Manager’s Expense Payments" [Draft; includes original annotations

<

p class=”MsoNormal”>Source: Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

<

p class=”MsoNormal”>

<

p class=”MsoNormal”>Draft Chiquita legal memorandum on payments to guerrilla groups in Colombia identifies members of the Security Department, John Stabler and Juan Manuel Alvarado.

<

p class=”MsoNormal”>

<

p class=”MsoNormal”>Document 05

<

p class=”MsoNormal”>

<

p class=”MsoNormal”>1999-04-27

<

p class=”MsoNormal”>[SEC Testimony of Jorge Forton], April 27, 1999, pp. 45-48.

Source: Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

Forton describes the challenge of auditing payments to guerrillas since the groups do not provide any kind of receipt.

Document 06

1999-04-27

[SEC Testimony of Jorge Forton], April 27, 1999, pp. 57-60.

Source: Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

Forton recounts a call with company staff who told him about a massacre of some 20 bus travelers in Urabá.

Document 07

1999-04-27

[SEC Testimony of Jorge Forton], April 27, 1999, pp. 89-92.

Source: Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

Forton says it was “questionable” whether payments to guerrillas were for self-protection or for “funding their activities.”

Document 08

1999-10-23

[SEC Testimony of John Ordman], November 23, 1999, pp. 121-128.

Source: Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

Ordman says there is “no way of determining” whether money channeled through the Security Department and third-party intermediaries ever reached the intended recipients.

Document 09

1999-12-15

[SEC Testimony of John Paul Olivo], December 15, 1999, pp. 61-64.

Source: Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

Olivo says his “concern since day one” was that he could never be sure that money intended for guerrillas and other groups was not being stolen by a third-party intermediary.

Document 10

2000-01-06

[SEC Testimony of Robert Kistinger], January 6, 2000, pp. 65-68.

Source: Freedom of Information Act Request to U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

Kistinger does not recall telling “Jorge” the way to know whether company funds had reached illegal armed groups was “if there are no killings.”

NOTE

[1] While the name of the SEC witness identified here as Jorge Forton was redacted from the transcript, there is abundant evidence indicating that Forton is the Chiquita witness interviewed by the SEC on April 27, 1999.

· A 1998 series in the Cincinnati Enquirer identified Forton as one of the officials central to the bribery case that triggered the SEC probe.

· The witness describes the role he played overseeing Chiquita’s financial operations in Colombia from 1994-1998, while an account for “Jorge Forton” on the popular social media network LinkedIn indicates that he held various positions at Chiquita from 1990-1998, including “Country Controller.”

· Throughout the testimony, the witness describes how he sent financial reports to his superiors about so-called “sensitive payments” that were made in Colombia, mainly to government officials and to guerrilla insurgent groups.

· The witness describes a conversation he had about these payments with a superior at the company: “… I questioned the nature of the payment. And he said: [Redacted], don’t get involved in this. I’m handling this and I know this is correct.” And basically, that was an invitation to get out. I mean, I wasn’t—I shouldn’t worry about questioning those payments, because, as I said, if no killings are, meaning that the payments were correct, reached the end user.”

· Another witness who has been separately identified as Robert Kistinger, is asked by the SEC about this same conversation during his later testimony: “[Redacted] also said that … that you had responded to him, “Jorge, if there are no killings, you know the money is getting to the guerrillas.”

· Another witness separately identified as Orlando Dangond mentions “Jorge” as being present at a key meeting where the bribe was discussed: “[Redacted] and myself may have explained to Jorge what had been going on, and then I believe [Redacted] explained to him about the payment.”

· While questioning a witness separately identified as John Ordman the SEC investigator mentions “Jorge Forton” during a discussion of how certain sensitive payments were recorded and reported to corporate headquarters: “… [T]his document related to Jorge Forton and this document contains disclosures…”

· Information at beginning of interview reveals that the witness is from Arequipa (assumed to be Peru). The LinkedIn account for Jorge Forton (mentioned above) says that he is a graduate of Catholic University of Santa María, a university in Arequipa, Peru.

Alexey Sinitsin, Head Expert of the American-Azerbaijani Progress Promotion Foundation

Alexey Sinitsin, Head Expert of the American-Azerbaijani Progress Promotion Foundation