While Nato was bombing its way to the Libyan oilfields, Turkey has been using “soft power” to assert its new-found foreign policy. Denied full membership of the European Union, largely by Germany and France, on flimsy grounds of “culture and identity”, Ankara’s foreign policy is increasingly drifting away from a Western orientation towards being Eastern-orientated, moving from the Global North to the Global South.

Although Turkey’s economic and political culture is deeply integrated into Europe, it has aggressively carved a diplomatic niche in the Iranian nuclear-enrichment crisis, Iraq, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and recently the Arab Spring. The global financial crisis has affected Turkish traditional markets in Europe and the United States, so it seeks to explore untapped markets in the Middle East and Africa.

Although Turkey’s economic and political culture is deeply integrated into Europe, it has aggressively carved a diplomatic niche in the Iranian nuclear-enrichment crisis, Iraq, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and recently the Arab Spring. The global financial crisis has affected Turkish traditional markets in Europe and the United States, so it seeks to explore untapped markets in the Middle East and Africa.

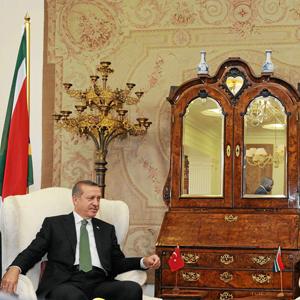

In Turkey’s calculations, South Africa is viewed as a strategic partner, particularly at this critical juncture in its attempt to develop an Africa agenda. It is within this context that the unusual state visit to South Africa by Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan earlier this month, must be understood.

The two countries share similar global outlooks on many matters affecting global governance. South Africa’s eyes are rightly fixed on the Brics, yet cultivating strong ties with countries such as Turkey should be a foreign-policy priority.

Turkey appears to be aware of its strategic objective in pursuing relations with South Africa. Does Pretoria have a strategy on Turkey? Can South Africa gain or lose in foreign-policy calculus by being closer to Ankara?

In the diplomatic arena, Pretoria’s stance on the urgent need to transform the economic and political institutions of global governance is largely shared by Ankara. Thus, the United Nations Security Council, the World Bank and International Montary Fund (IMF) should be democratic and truly representative of all regions of the world. South Africa and Turkey are both members of the G20, and have been working closely to reshape the global economic order into one that is more representative of emerging markets and the developing world.

As it stands, Turkey’s chances of being the next Brics member are very good. In 2003, Pretoria and Ankara both vehemently opposed the unlawful American invasion of Iraq. Turkey sacrificed its strategic relations with Washington by refusing the use of its territory as a launchpad in the US’s disastrous war against Iraq under Saddam Hussein.

Support for Palestine

South Africa and Turkey support the Palestinian yearning for statehood and have repeatedly condemned the use of violence by both sides. Addressing the Arab League, Erdogan noted that recognition of a Palestinian state is “not an option but an obligation”. On many occasions Erdogan has offered a vocal critique of Israeli actions: in Gaza, on the Mavi Marmara incident, and elsewhere.

Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu said: “Israel is out of touch with the region and unable to perceive the changes taking place, which makes it impossible for the country to have healthy relations with its neighbors.”

Both South Africa and Turkey are opposed to nuclear proliferation but support the right of countries to use nuclear power for peaceful purposes. The two countries’ view of Iran’s dispute with Western countries, led by the US, over the enrichment of uranium, is a good example. They both seek a peaceful resolution to the Iranian nuclear-enrichment crisis. Given its geographical proximity to the Middle East, Turkey plays a greater leadership role in this than South Africa.

Yet tight diplomatic relations between Pretoria and Ankara will strengthen South Africa’s Middle East policy. South Africa is seen as a champion in peaceful negotiation, the mediation of political conflicts and peacekeeping, as well as post-conflict reconstruction and development. Turkey might want to learn from South Africa how to resolve conflicts in its neighborhood (it has a territorial dispute with Cyprus).

The Arab Spring has, unexpectedly, benefited Ankara more than Nato. Egypt’s future leadership in the Middle East region has been weakened by uncertainty about its political stability. On his recent state visit to post-Mubarak Egypt, Erdogan sold the Turkish model of democracy, saying: “Do not be wary of secularism. I hope there will be a secular state in Egypt.”

The major point he made was that “secularism is compatible with Islam”. This view appears to be welcome in Libya. The head of the Transitional National Council (TNC), Mustafa Abdel Jailil, said: “We will not accept any extremist ideology, on the right or the left. We are a Muslim people, for a moderate Islam.”

South Africa could use Erdogan’s growing influence to reach out to the new players in Libya, Tunisia and Egypt to achieve peace and security, in line with its African agenda. More importantly, Turkey’s expanding economy requires Africa’s energy and markets.

Development and finance

The country is renowned in the spheres of infrastructure development and development finance. It should not only be the South African government that is thinking seriously about Turkey, but business, labour and civil society as well.

Like Turkey, South Africa must balance its diplomatic relations with both developed and developing countries. Universities in South Africa and Turkey can share and exchange knowledge in numerous academic fields. While Turkey can teach the world how to balance secularism and Islam on the doorstep of Europe, South Africa remains a beacon of hope as it strives to be multi-religious and multiracial.

Although South Africa is battling to close the widening inequality gaps between racial, gender and other groups, it has made huge strides in just two decades on deep structural and historical divisions.

Turkey’s experience has lessons for South Africa and the region in a number of development areas, but South Africa’s experience in advancing a non-sectarian democratic order and in accommodating minorities, both non-African and African, may offer Turkey some lessons too.

David Monyae is an independent international-relations expert