At least all those non-EU citizens wanting to live and work in the European Union now know where Malta stands. If they have a spare €650,000, plus more for dependents, they will be able to treat the whole family to Maltese passports. In so doing, they will effectively buy full access to all 28 EU countries – and the right to visit many others visa-free.

However Malta’s move is viewed – and Brussels is not happy, but currently has no mechanism to prevent it – there is virtue in clarity.

According to Chatham House for a brief period, a limited number of rich people will be able to obtain citizenship of an EU country by contributing to a Maltese development fund. Such paid-for provisions are not unheard of: Britain and others already offer a path to citizenship for £1 million-plus investors.

But Malta’s scheme, as originally concieved, differs in having no residence requirement. It really is offering a passport of convenience.

Some might reasonably object that the fuss about Maltese passports ignores the ease with which members of the global elite – aside from those expressly blacklisted – are already able to cross borders. It is the rest, including the new middle classes of the emerging economies, for whom visa restrictions are burdensome. And frustrated applicants reserve some of their most bitter complaints for Britain.

The point was made pithily a few years ago by the Russian liberal politician, Grigory Yavlinsky, when he spoke at Chatham House. After making a plea for Britain to relax visa restrictions on Russians, he remarked with heavy sarcasm that there were some Russians, including those with dubious pasts, for whom entry to the UK was no problem.

To judge by my inbox, the ill-feeling generated by the British visa system has only increased. Many complaints are about delays, costs and carelessness with crucial documents. But recurrent themes are the supercilious attitude of officials and a perception that the rules are applied both inflexibly – formulaic box-ticking – and arbitrarily.

In recent months, I have learnt of several individuals from former Soviet states whose applications to visit relatives for a short stay have been turned down, even though they have visited regularly over several years. I have also attended conferences where featured speakers have received their visas late or not at all.

Unfavourable comparisons are made with other EU countries in the Schengen zone – the 22 EU members which have abolished passport controls at their common borders – or even with the United States.

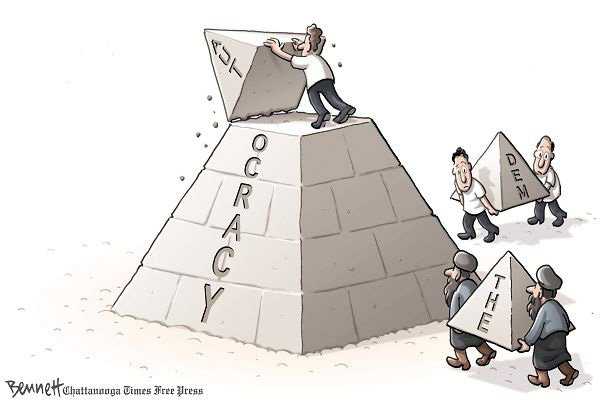

Part of the explanation may be the ambivalence and sheer muddled thinking that often seems to prevail at the very top. On the one hand, the British Government has an electoral mandate for a sharp reduction in immigration. Yet its toughest talk concerns prospective new arrivals from Romania and Bulgaria – about whom it can actually do nothing.

On the other hand, it is keen to attract ever more overseas (non-EU) students, while refusing them the right to stay after graduation.

Looking enviously across at France, it also wants many more tourists, especially those, such as high-spending Chinese, of whom France attracted six times more than Britain last year.

To this end, the Chancellor, George Osborne, recently proposed simplifying the visa rules for Chinese business people and tour groups if they were also applying for a visa from one of the Schengen countries. France has since gone one better by providing a 48-hour service. The race for the Chinese yuan is on.

However, Britain’s efforts to be competitive have only introduced more inconsistencies. Membership of Schengen has been rejected by successive UK governments on the grounds that it would mean contracting out border security to other EU countries. Yet, as is now tacitly acknowledged, nonmembership puts Britain at a disadvantage in the tourism stakes. So it has come close to accepting the Schengen visa process in practice, but only for well-heeled Chinese.

One consequence could be resentment on the part of others, including those from the Commonwealth and the former Soviet Union. Individual visitors – relatives, artists, performers or academics – already feel they receive short shrift. Positive discrimination for Chinese business people and shoppers could only make matters worse.

UK visas are a particularly sore point among Russians, with the British authorities stressing security concerns, and Moscow insisting that any liberalization be reciprocal. It would be facetious to suggest that the new arrangements for Chinese could be extended to others – by requiring, say, sponsoring organizations, to include generous shopping vouchers with their invitations.

But should the way to a British visa really lie through Harrods? There must be a more equitable, less mercenary, way.