|

|

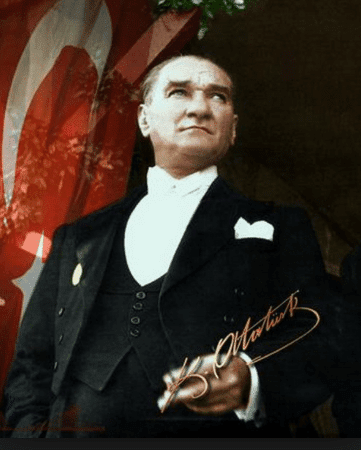

Invitation to Remembrance Ceremony to Honor Atatürk

|

|

| Atatürk Society of America | 10:55 PM (14 minutes ago)

|

||

|

|||

|

|

|

|

| Atatürk Society of America | 10:55 PM (14 minutes ago)

|

||

|

|||

From: Demirtas Bayar [mailto:Demirtas@CelalBayar.org]

New York Times – NOV. 7, 2015

SundayReview | Op-Ed Columnist

Roger Cohen

SANLIURFA, Turkey — ABOVE a restaurant specializing in sheep’s head soup, with steaming tureens of broth in the window, two young Syrian journalists took up residence in this ancient town in southeastern Turkey. They had fled Raqqa, the stronghold in Syria of the Islamic State, or ISIS, and devoted their time to denouncing the crimes of the barbarous jihadi group. Today, their second-floor apartment is a crime scene, with a red police seal on the door.

On Oct. 30, the Islamic State beheaded Ibrahim Abdel Qader, age 22, and slit the throat of 20-year-old Fares Hammadi. They later posted a video of their handiwork, saying enemies “will never be safe from the blade of the Islamic State.” The killers have not been found; a new unease inhabits this bustling town about 30 miles from the Syrian border. “It was shocking to have a first beheading in Turkey,” Omer Yilmaz, the owner of the restaurant, told me. “We are used to bullets, but that, no. To slaughter a human like an animal is unthinkable.”

The unthinkable is becoming conceivable in a combustible Turkey. Syrian violence has seeped over the border. The Islamic State is now entangled in the age-old conflict of Turks and Kurds. During several days near the Syrian border, often in areas with Kurdish majorities, I found simmering anger among Kurds and predictions of worsening bloodshed.

The Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, bolstered by the electoral triumph of his conservative Islamist Justice and Development Party, or A.K.P., has shown a troubling penchant for benign neglect toward the jihadi Islamists — enough for them to establish a Turkish network.

What does Erdogan — in theory a key American ally leading a NATO state — see in the knife-wielding jihadis of the Islamic State? They are useful in confronting Turkey’s nemesis, the Kurds, who have taken over wide sections of northern Syria and established self-government in an area they call Rojava. That in turn has raised the specter of a border-straddling Kurdistan, the nightmare of the Turkish republic.

Hence the unpersuasive Turkish balancing act that sees Erdogan offering the United States use of Turkish air bases to fight the Islamic State even as Turkey twice strikes the positions in Syria of Kurdish militias who, as my colleague Tim Arango put it, are the “most important allies within Syria of the American-led coalition fighting the Islamic State.” Hence, also, the bungling and inaction that produced, on Oct. 10 in Ankara, the worst terrorist attack in Turkish history.

The Ankara suicide bombing followed another suicide bombing in the border town of Suruc that killed 33 pro-Kurdish activists in July.

One of the Ankara suicide bombers was the older brother of the Suruc suicide bomber. Their father tried without success to alert the government to the danger. Almost three months elapsed between the bombings, both of which principally targeted Kurds, and Erdogan did nothing. After the Ankara attack, his prime minister, Ahmet Davutoglu, said the government had a list of potential suicide bombers but could not detain them because “as a country with rule of law, you can’t arrest them until they act.” (Not easy to do afterward either.) These words were uttered even as countless Kurdish militants were rounded up in the months between the June and November elections.

The impression has been inescapable that, for the government, having Islamic State militants kill Kurds with impunity was a palatable option with the bonus of creating the climate of instability that secured the Nov. 1 electoral victory for Erdogan.

For Erdogan’s A.K.P. government, the terrorist organization par excellence is the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or P.K.K., which has fought an intermittent insurgency against Turkey since the 1980s, is linked to the Kurdish militias in Syria and is designated a terrorist group by the United States. The president, infused with post-electoral vim, vowed this week to fight P.K.K. members until they would lay down their weapons “and pour concrete over them.” The Islamic State, by comparison, is the object of no such ruthless language or action.

I found Gultan Kisanak, the mayor of Diyarbakir, the effective capital of Kurdish aspirations for autonomy within Turkey, watering roses on the terrace outside her office. There was not a cloud in the sky on a mild late-fall day. But her mood was grim. Kisanak is a member of the Kurdish-dominated Peoples’ Democratic Party, or H.D.P., which took over 70 percent of the vote in Diyarbakir but saw its national vote share fall to 10.7 percent from 13.1 percent in June as Erdogan’s fear tactics worked. “ISIS became such a large force thanks to an open-door policy from Ankara,” she told me. “Militants come and go. ISIS has been delegated to fight a proxy war against Kurdish Rojava, and all kinds of support has been given to them.”

THE government dismisses such suggestions. Did Turkey not, in extremis and under great international pressure, allow arms to reach the Kurdish-held Syrian town of Kobani and so prevent its fall to the Islamic State? Are Turkish air bases not being used by the American-led coalition? Do the Kurds not have in the H.D.P. representation in Parliament, as well as control of many municipalities? What do the Kurds want that they do not already have unless it’s territory — and that Turkey will never give.

“For us, ISIS and the P.K.K. have the same aim,” Abdurrahman Yetkin, a prominent businessman and Erdogan supporter in Sanliurfa, told me. “Both organizations are being used by external powers to destabilize Turkey.”

You hear a lot of such talk from the Erdogan camp these days — talk that implausibly conflates Islamist jihadis and Kurdish militants, as in the official characterization of the Ankara bombing as a “cocktail” involving both. It is this sort of manipulation of the facts that undermines the government’s insistence that it’s in the Islamic State fight for real.

Certainly it is targeting the Kurds. The P.K.K. made a big mistake by answering Suruc with the killing of two Turkish policemen. Violence could only serve Erdogan, who embarked on a fierce bombing campaign on P.K.K. strongholds in northern Iraq and has shown equal ruthlessness within Turkey. Diyarbakir and other majority Kurdish towns in the southeast have been under intermittent curfew. Attempts to establish autonomy in certain city districts have been crushed.

Reeling back what he has unleashed after a dozen years in power is going to be hard for Erdogan. Power and money seem to have gone to his head. Turkey has veered into violence and polarization. “Erdogan is scared and he deals with it by making everyone more scared than he is,” Soli Ozel, a university lecturer, told me.

The Turkish president needs to get back to the negotiating table with the Kurds, get serious about crushing the Islamic State in Turkey and beyond, ensure a transparent and credible investigation of the brutal killings in Suruc and Ankara (as well as the double murder in Sanliurfa) and stop his assault on a free press. President Obama should press his ally hard on all these fronts.

Turkey, a heterogeneous nation, cannot be homogenized under the banner of Erdogan’s Sunni Islamist nationalism. Intolerance will backfire, as it has in Syria. “They don’t want the Kurds even to breathe,” Ahmet Turk, the mayor of the beautiful southern town of Mardin, told me. “Kurds do not want violence, but if Erdogan does not stop, things could get much worse.”

In Sanliurfa, as night fell, I met Ahmed Abdel Qader, the older brother of the beheaded journalist. He told me, “The guys who did this killing are now threatening me.” His dark eyes seemed haunted. Turkey’s tide of violence, cynically cultivated, must now be curbed. It won’t be easy.

Ben Aris

|

|||||||

|

Digit Tests and the Peculiar Election Dynamics of Turkey… Sunday’s elections in Turkey were a landslide for the ruling AKP. Its vote share rose nearly 9 percentage points from what it received in June. One interpretation i…

|

|||||||

|

View on erikmeyersson.com

|

Preview by Yahoo

|

||||||

Kurdish People’s Protection Units, or YPG, fighters rest in Tal Abyad, Syria on June 19, 2015.

Kurdish People’s Protection Units, or YPG, fighters rest in Tal Abyad, Syria on June 19, 2015.ISTANBUL — The U.S. acknowledged on Wednesday that it has been supporting Kurdish forces in Syria with American aircraft deployed in Turkey, adding another tangle to its strategy to defeat the Islamic State group that hints at the precariousness of the entire campaign.

Col. Steve Warren, a spokesman for the U.S. campaign against the extremists in Iraq and Syria, detailed that decision in a press briefing on Wednesday. The U.S. announced on Oct. 30 that it had based A-10 fixed-wing aircraft at Turkey’s Incirlik air base in the country’s southeast, Warren said. Those aircraft have since provided air support for Syrian fighters in a Kurd-Arab coalition in battles against Islamic State positions in northeast Syria’s Al-Hawl region.

Though the U.S. has launched airstrikes to help Kurdish fighters in Syria fight the Islamic State since last fall, Warren’s comments appear to be the most public admission that it is doing so from a base in Turkey — a NATO ally that is skeptical of the Syrian Kurds and only granted the U.S. full flight capabilities at its Incirlik base this past July. Col. Christopher Garver, a public affairs officer for the anti-ISIS campaign, told HuffPost in a Friday email that U.S. flights out of Incirlik have previously aided Kurdish fighters as well.

Warren was careful to note that the ground forces the U.S. was supporting were under the umbrella of the Syrian Democratic Forces, a recently formed alliance of Kurds, Arabs, Turks and Syrian Christians announced just last month. The Arab component of those forces was involved in the anti-IS offensive, which “is important because Al-Hawl is predominantly an Arab area,” Warren specified.

But that Kurd-dominated coalition is widely seen as a politically convenient invention, cobbled together so the U.S. can funnel significant support to effective Kurdish fighters and their allies — as it did with an Oct. 12 airdrop — while saying it is engaging Sunni Arabs, the majority community in Syria.

YPG fighters pose as they stand near a checkpoint in the outskirts of the destroyed Syrian town of Kobane on June 20.

Talk of the new force gave Washington cover to send arms that could be used against IS without angering Turkey, a State Department official told The WorldPost soon after the airdrop. One administration official called the approach a “ploy” in a conversation with Bloomberg View. And a New York Times reporter who visited the northern Syrian regions home to the new alliance published a damning report on Nov. 2 that said the loosely aligned Syrian Democratic Forces exist “in name only.”

While Turkey and the Syrian Kurds share the goal of undermining the Islamic State, the two U.S. partners deeply mistrust each other. Turkey accuses the dominant political group among Syria’s Kurds, the PYD, of being a branch of a Kurdish militant organization called the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK. The PKK has waged war on Ankara for three decades in the name of Kurdish rights.

Many Kurds, meanwhile, believe Turkey has aided the rise of extremists during the Syrian civil war and note that Kurdish forces have done more to damage IS on the ground than any Turkish action has. Though these tensions have mostly been expressed verbally, Turkey shelled Syrian Kurdish positions on Oct. 27

Analysts worry Washington’s new maneuver could lose either the support of the Kurds — who are reportedly attempting to strengthen ties with Russia, now a key player in the Syrian war — or the Turks, whose military and geographic position make them key to any effort to change the situation in Syria.

Washington’s balancing act between Turkey and the Kurds has worked thus far. But its willingness to now publicly acknowledge support for the PYD from Incirlik could force it to choose between reducing support to the Kurds, the strongest anti-IS force, or placing more pressure on the Turks, who have great influence over the situation in Syria.

“We’re not trying to cover anything up,” Warren said during his briefing when asked by a reporter to respond to the New York Times report. “We’re providing weapons, or in this case, ammunition, to the Syrian Arab coalition. That’s what we said we’re doing, that’s actually what we’re doing.”

A Turkish official made clear to The WorldPost that his government remains worried about the Kurds in Syria.

“We are deeply concerned about the PYD’s links to the PKK,” the official said. Turkey ended a ceasefire with the PKK in July and has been striking the group in Turkey’s Kurdish-majority southeast and in Iraq ever since. The Kurdish militants have claimed respons

Ankara shows no evidence of letting up after Sunday’s election, in which President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party won back majority rule after painting the campaign as a choice between chaos and stability. Erdogan has vowed to “liquidate” every PKK fighter.

Turkey’s government was not yet prepared to comment on the U.S. strikes launched from Incirlik, however, the official added.

“Another concern is that divisions among opposition forces will ultimately serve the regime’s interest,” the official added, vocalizing a commonly reiterated state allegation that the Kurds care more about their own interests than the broader future of Syria.

Turkey is a staunch opponent of Syrian dictator President Bashar Assad, and it supports a range of Syrian Arab groups that are trying to bring down his regime. Ankara and many members of those Syrian opposition groups are wary of the Kurds because they have allowed some regime forces to remain in the Kurdish city of Hasakah, and because they believe the Kurds want a de facto break-up of Syria.

Firefighters extinguish the fire after a car bomb attack on YPG headquarters in Hasakah, Syria on September 15, 2015. At least nine people were killed and other 30 people wounded after the attack.

Firefighters extinguish the fire after a car bomb attack on YPG headquarters in Hasakah, Syria on September 15, 2015. At least nine people were killed and other 30 people wounded after the attack.Arabs in areas captured by the Kurds with U.S. support have also reported abuse at the hands of Kurdish forces, in interviews with outlets including The WorldPost and advocacy organizations like Amnesty International. Those allegations suggest that the Turks may have a point: If Washington does empower the Kurds without real engagement with Sunni Arabs, it could push many Arabs into the embrace of the Islamic State or other extremist, anti-Western groups in Syria.

The U.S. appears to be managing Turkey’s concerns by tacitly agreeing that Syrian Kurdish forces will not be allowed to pass into areas west of the Euphrates river, according to Aaron Stein, a Turkey expert at the Atlantic Council.

Turkey is nervous that the success of the Syrian Kurds will inspire Kurds in Turkey to try and carve out their own statelets, and it pointed to the Euphrates as a red line when announcing its recent attacks on the Syrian Kurds. Ankara fears Syrian Kurdish forces will connect the areas they control in northeast Syria to their third region, or canton, in the northwest, thereby creating a powerful Kurdish corridor along the Turkey-Syria border.

The focus on vanquishing the Islamic State, which U.S. officials say will only happen with help from the Syrian Kurds, puts Turkish policymakers in a difficult position.

“In any case, Turkey is certainly indirectly aiding the YPG’s advance east of the Euphrates,” Stein told The WorldPost, using the acronym for the Syrian Kurds’ fighting force. “American drones provide intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance for these missions, and tankers based at Incirlik most certainly refuel U.S. bombers flying from Qatar.”

Max Hoffman, a policy analyst at the Center for American Progress, told The WorldPost that the U.S. seems largely willing to pursue its goal of bringing down IS regardless of Turkish sensitivities.

“It seems unlikely to me that coalition air controllers would ignore a credible ISIS target relayed by YPG on the ground, or divert coalition aircraft from further away, just because the closest coalition airplane was launched from Incirlik,” Hoffman wrote in a Wednesday email. “But I have no way of confirming that, and it’s certainly in the U.S. interest to allow Turkey to preserve that useful political fiction [that the Kurds are not supported from Incirlik] (if it is, in fact, a fiction).”

YPG fighters in downtown Tal Abyad, Syria on June 19, 2015.

YPG fighters in downtown Tal Abyad, Syria on June 19, 2015.The U.S has struggled to find reliable partners against the Islamic State on the ground other than the Kurds and an array of Arab-dominated groups the CIA has armed to fight Assad. In early October, the Obama administration announced that a $500 million Pentagon program to train anti-IS Syrian rebels had largely failed and was being restructured.

The White House’s approach now seems to be to support the Kurds and nationalist Arabs in the north as intensely as possible. It announced on Oct. 30 that President Barack Obama would deploy dozens of American special operations forces to northern Syria to coordinate airstrikes and arms supply.

The war in Syria has claimed at least 250,000 Syrian lives. With no end in sight to the conflict, IS remains in control of large tracts of land and the Assad regime continues to kill civilians daily, prolonging a conflict that has forced millions to seek refuge in neighboring countries and fueled the largest mass migration of people since World War II.

International players involved in the conflict — either supporting Assad or the opposition to him — are holding negotiations to work out whether the dictator can be removed so that a more stable Syria can be established, but those talks have yet to bear fruit.

The latest round, involving the U.S., Turkey, and states like Russia and Iran that are helping Assad, concluded without significant progress last week.

This story has been updated to include Garver’s comments about ealrier U.S. aid to Kurdish fighters.

Sophia Jones reported from Istanbul and Akbar Shahid Ahmed reported from Washington.

By Ferruh Demirmen, Ph.D.

AVİM, Center for Eurasian Studies

October 26, 2015

When Pope Francis, during a Mass in St. Peter’s Basilica on April 12, 2015, pronounced the word “genocide” in reference to the 1915 events in Ottoman Anatolia a century ago, it was patently clear that he was delving into territory he should not have. It was a meeting where the pontiff and top Armenian clerics and Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan had gathered in what was apparently a show of Christian solidarity.

By recognizing “Armenian genocide,” and calling the Armenian victims “confessors and martyrs for the name of Christ,” the Pope was asserting an unproven event, revealing his prejudice, or at the vey best, his misjudgment. The recent decision from the Grand Chamber of the prestigious European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) is a testimony to the Pope’s wrongful and deplorable stance on Armenian allegations.

In its milestone decision announced on October 15, 2015, the Grand Chamber, by a majority vote, agreed with the Second (lower) Chamber’s 17 December 2013 decision that Switzerland had violated Turkish politician Doğu Perinçek’s right to freedom of expression when it imposed penalty on Perinçek in connection with his “denial of Armenian genocide.” Hoping to have the lower chamber’s decision reversed, Switzerland, under intense Armenian lobbying, had appealed that decision to Grand Chamber – obviously to no avail.

The Grand Chamber’s decision had two equally important ramifications. By letting stand the lower chamber’s decision, the Grand Chamber in effect affirmed that: (a) “Armenian genocide” is controversial and unproven, (b) there can be no comparison between the 1915 events and Holocaust.

The court’s position is consistent with the provisions of the 1948 UN Convention on Genocide (ratified in 1951), which first codified this term. According to this Convention, genocide is a legally construed special crime, and it can only be established through a judicial process in a duly authorized court – an international court or a court where the alleged crime was committed. Without a verdict from such a court, labeling an event as genocide lacks legal validity. In other words, it is merely an opinion.

To date there exists not a single court verdict characterizing the 1915 events as genocide. The UN has also refused to call the 1915 events genocide. When he decided to recognize “Armenian genocide,” the Pope should have been aware of these legal boundaries. ECHR is an organ of the 47-member Council of Europe.

So, one must ask, absent a judicial verdict, what gave the Pope the authority to call the 1915 events “genocide”?

In its February 3, 2015 ruling (Croatia v. Serbia), the International Court of Justice in The Hague also concluded that forced relocation, which is what happened in Anatolia in 1915, even if it results in killings, cannot be called genocide unless specific intent (dolus specialis) to harm or kill is proven. The court also held that the provisions of the 1948 Convention cannot be applied retroactively, i.e., judgments as to past events not permissible.

In the U.S. the Bill of Rights protects a party from being labeled guilty of a crime without due process; i.e., the alleged crime must be adjudicated in a court of law. The old, venerable adage, “Innocent until proven guilty,” must be respected.

It is obvious that by labelling the 1915 events as genocide the Pope exceeded his authority and violated both the European and American due-process standards. The same standards, in fact, also bind parliaments that have so far recognized “Armenian genocide.”

To date, the Armenian side, out of fear it would lose, has refrained from litigating its case in a court of law, preferring to influence the public opinion through propaganda instead.

A case in point is the 17 December 2003 order of the European Court of First Instance on a lawsuit lodged by a group of Armenian-French citizens against three European institutions including the Council of the European Union. The applicants had sought compensation for non-material damage suffered on account of, inter alia, recognition of Turkey’s status as a candidate for accession to the EU without Turkey’s prior acknowledgment of Armenian genocide. The court found that the applicants’ action was without legal merit and dismissed the claim, adding that the European Parliament’s 1987 resolution calling on Turkey to recognize “Armenian genocide” was purely political, without any binding consequences. Appeal of the ruling to the higher court was dismissed.

The case was a legal defeat for the Armenian side, also reaffirming the fact that Armenian “g” resolutions passed by parliaments are no more than political opinions.

Such realization should prompt parliaments that have recognized Armenian “g” to date to re-think their stance and rescind their decisions. The 1948 Convention does not make a distinction between “political” and “legal” recognition of genocide.

The Pope, of course, has the right to express his opinion on the 1915 events; but this is not the same thing as denouncing these events as proven genocide.

Speaking of opinion, in 1985 69 U.S. historians and researches signed a declaration, published in New York Times and Washington Post, stating that in their opinion the 1915 events do not constitute genocide. Among the signatories were eminent scholars such as Bernard Lewis. Surely, the Pope should have been aware of this declaration. Hence, even as regards opinion, there is no consensus among the scholars on “Armenian genocide.”

The Pope apparently is also not aware that in 1920 his predecessor Pope Benedict XV had pleaded with the British to release some of the high-ranking Ottoman officials who were being held on the Island of Malta on suspicion of complicity in massacring Armenians. Benedict XV, who had direct contact with the Ottoman authorities, obviously did not think the Ottoman government had murderous or genocidal intentions toward the Armenians. All 244 Malta detainees, in fact, were released by the British for lack of evidence and returned to Turkish soil.

So, one must ask the Pope: What did he know about the 1915 events in 2015 that his predecessor Benedict XV did not know almost a century earlier?

Human rights issue

The Pope, while recognizing “Armenian genocide,” astonishingly did not express any compassion for more than half a million civilian Muslims that lost their lives at the hands of renegade Armenian bands during the 1915 Armenian revolt.

In a gesture of humanity, the Pope could have also offered condolences to the relatives of 42 Turkish diplomats and 4 foreign diplomats that were assassinated by Armenian terrorists in the 1970s through 1990s – including Turkish ambassador to Vatican Taha Carım in 1977. Three years later, in 1980, Carım’s successor Vecdi Türel and his driver were wounded by the terrorists.

Likewise, the Pope could have expressed his compassion for the memory of the more than 600 Azeri civilians massacred by Armenian forces in the town of Khojaly in 1992.

The Pope’s “humanity” should not be limited by race, religion or ethnicity.

The 1.5 million Armenian victims alluded to by the Pope is also a grotesque exaggeration. The Armenian losses in Anatolia during World War I from all causes including fighting on the sides of the Allies were roughly 300,000, some 57,000 of which were during the relocation itself, most of them due to disease, famine and chaos.

Double standard

When he visited Sarajevo in June 2015, His Holiness, while denouncing the massacres inflicted upon the Bosnian Muslims in Srebrenica, refused to use the term “genocide.” This, despite the fact that two UN courts have unequivocally called the Srebrenica massacres genocide. The Pope ignored the appeals of Bosnian academics and representatives of war victims to recognize the massacres as genocide. Srebrenica in a sense is a stone-throwing distance from the Holy See.

Reflecting a shameful double standard, the Pope could not bring himself to use the word “genocide” when the perpetrators are Christian and the victims Muslim.

In conclusion, His Holiness should deal with matters of faith and stay away from highly-charged historical issues that sow discord and hatred in society. He should not readily accept Armenian “g” allegations presented to him on a gold platter by the Armenian side. Otherwise, his call for inter-faith and inter-communal dialog becomes shamefully hollow.

OTTAWA – The Leader of the Liberal Party of Canada, Justin Trudeau, today issued the following statement on the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide:

“Today, we commemorate the centennial anniversary of the Armenian Genocide; an event which saw the destruction of the national and personal freedom of over a million people during and after the First World War.

“By recognizing the atrocities of the Armenian Genocide, we are reminded of the pain and suffering endured by those affected, as we endeavor to achieve peace and reconciliation for the people of Armenia, and a stable and prosperous future for all of its citizens.

“While the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide is a time for solemn remembrance, it also provides us with the opportunity to reaffirm our commitment to never again be indifferent to hatred and genocide, nor remain silent to those who discriminate against others based on characteristics such as race, gender, or sexual orientation.

“On behalf of the Liberal Party of Canada and the entire Liberal Caucus, I stand with Canadians across the country as we honour the memories of the victims of the Armenian Genocide.”

Kaynak: » Statement by Liberal Party of Canada Leader Justin Trudeau on the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide – liberal.ca