Author: Matthew Gullo, Deputy Editor, Centre for Policy and Research on Turkey Date: Jun 10, 2016

Turkey’s Power Play: The Creation of an Indigenous Military Industry and its Neo-Ottoman Offensive

By Matthew. T.Gullo[*]

Abstract

This paper examines Turkey’s nascent indigenous military industry and its future implications towards Turkish foreign policy. Through a construction of a two-level (domestic and international) analysis of current and previous Turkish politics that is juxtaposed by global trends and theories of international relations, this paper will present how Turkey’s new hard-power component has the potential to become a significant lever in its foreign affairs (neo-Ottoman) engagement. Through this analysis, this paper hypothesise that the utilisation of an indigenous military industry serves as a catalyst for achieving two imperative foreign policy objectives for the Turkish State. First, it will help Turkey proliferate its influence in the Middle East through military transfers. Second, it will simultaneously create autonomy for itself in the international political system by ridding itself of foreign dependencies pertaining to its armed forces. These objectives are part of Turkey’s purposeful plan to pursue an independent foreign policy that is less constrained and less beholden towards any specific geopolitical orientation; especially one that is centred on NATO, Europe, and the United States of America, as it aspires to be recognized as an independent and influential global player on the international stage.

***

Introduction

In recent years, the Republic of Turkey has been on a “soft power” offensive to win regional influence vis-à-vis a purposeful cultural and civic resurgence aimed at the Middle East, which is sometimes referred to as neo-Ottomanism.[1] However, a less covered and arguably more powerful offensive to cultivate regional influence has been concurrently developing in Turkey, and that has been its unencumbered drive to establish itself as an important global military exporter with the creation of its own indigenous national military industry. If this ambition is fully realised, Turkey will be less constrained by its hard power requirements, while simultaneously being able to project power more broadly; thereby, creating an opportunity to establish a more autonomous foreign policy with the eventual ability to further influence the politics of the Middle East and those of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

The importance of self-sufficient military equipping has been well documented in statecraft throughout history. From Niccolo Machiavelli’s commentary regarding the demise of Sforza dynasty due in part to their reliance on mercenaries, to Charles de Gaulle’s Force de Frappe, to Kenneth Waltz’s “self-help” framework; an underlying theme of nations and the deployment of the instruments of war has been widely consistent: an independent, reliable, and home-grown defence is the only certain insurance for the ability to resist against unsolicited violent or nonviolent subjection.[2] In fact, in an age where great powers are constantly vying to influence minor or middle powers, the traditional formula used to leverage weaker states (inter alia coercive diplomacy) has been either through economic incentives or sanctions, or by controlling the flow of weaponry into a state.[3] An example of the latter has been the United States’ military assistance to Egypt since the 1978 Camp David Accords.[4] States that are band wagoning, a junior partner in an alliance, or not fully responsible or capable for providing for their national defence are more often than not required to kowtow to the demands of the greater power when interests diverge or when the geopolitical landscape changes.[5] Although, hard power is not the sole variable that governs a state’s ability to project power or to conduct statecraft, a military dependency, like all dependencies, places a constraint on a state’s capacity to independently conduct statecraft.

States simply do not only use their hard power capabilities to survive in our anarchical world that is buttressed by the inherent competition and selfishness of the human condition. It is an additional mechanism to influence and project power on its competitors. As discussed in Thomas Schelling’s seminal work Arms and Influence, one aim of states in regards to their militaries is to achieve an advantageous bargaining position that comes from the capacity to hurt other states.[6] In this regard, the well-equipping of the military or paramilitary forces is pivotal for conducting statecraft, especially if there is a direct underlining threat domestically or transnationally. Therefore, states that are unable to meet their military demand (need) through domestic reliance, can potentially become less autonomous in the international political system and unable to utilize or project power multidimensionality. At the same time, states that can establish a dependency over others can reap potential benefits or achieve gains through strategic coercive diplomacy.[7]

Turkey as the third-largest conventional weapons importer in the world still relies significantly on the West, in particular the United States, for supplying its armed forces.[8] However, unlike during the Cold War and early post-Cold War period where over 80% of its military need was fulfilled internationally, Turkey has started to counter-balance its dependency on its military need. Currently, it now meets over half its defence requirements domestically while striving to meet all of its military domestically by 2023.[9] Additionally, Turkey has made sizeable investments in its own domestic weapon production, and also contributes in producing parts for NATO sponsored war materiel, such as, the F-22 and F-35 programs.[10] In 2011, the Turkish Navy commissioned its first domestically produced Ada class ASW Corvette with the launching of the TCG Heybeliada, and its military industry’s centrepiece, the Altay battle tank, is expected to go into full service by 2018, marking Turkey’s first domestically produced tank.[11]

Similar to Turkey’s former soft power offensive to generate influence in the Middle East, the creation of an indigenous military industry is also a calculated strategic manoeuvre aimed at bolstering Turkey’s position in world affairs. This initiative stems from a wider “neo-Ottoman” foreign policy doctrine that seeks to rid Turkey of its dependencies, which at times has left it vulnerable and constrained by the influence of foreign powers, and runs in parallel with its ambition to garner greater influence over current states that were geographically apart of the Ottoman Empire.[12] By looking at how this new hard power corresponds to Turkish foreign policy ambition, this paper will: review how Turkey’s military industry can reignite Turkish foreign policy and lay the foundation for hypotheses of the potential gains of an indigenous new military industry, and present possible geopolitical ramifications for the Middle East and NATO.[13]

The primary focus of this paper will be to examine Turkey’s indigenous military industry to create a hypothesis on its implications towards the future state of Turkish international relations. To acutely posit how Turkey’s indigenous military industry can reshape its foreign affairs, this paper will: (i) analyse Turkey’s nascent military industry and its current investment, exporting record, and future growth projections; (ii) review the historical record at two-levels (domestic and international) of how the Turkish State has been constrained by its dependency on its foreign military needs and by being a junior member of the Eurasian alliance structure. This analysis will flow into, (iii) how two overlapping factors: (a) neo-Ottomanism, and (b) non-polarity are having a tremendous impact on the foundation of the Turkey’s neo-Ottomanism foreign affairs doctrine, Lastly, (iv); an amalgamation of previous sections will be constructed to hypothesize what a future state of Turkish foreign affairs should look like given its new hard-power means that is being driven by a neo-Ottoman doctrine.

Turkey’s Military Industry

Throughout the last decade, Turkey has moved towards indigenous military manufacturing and development, and through key technology transfers and co-production contracts (when equipment is built outside of Turkey), it has been able to build up a formidable defence industry.[14] Turkish military exports are on the rise, while the proportion of foreign equipment in its armed forces has been falling annually.[15] Ankara has also spent over $1 billion on its defence research and development in 2014, making it the largest research and development investment sector in the country.[16] Turkey’s investment in defence technology and manufacturing has slowly ebbed away at its dependency on importing foreign military equipment, as well as, created business for its growing defence sector. Several major defence companies have been established (both ASELSAN and TUSAS have already broken into the top 100 global defence firms) as Turkey seeks to create global brands in the defence sector.[17]

Boosting defence sales in addition to producing more military items locally has been an intricate part of Turkey’s current five-year strategic plan and also a tremendous source of national pride.[18] According to the Savunma Sanayii Müsteşarlığı (SSM), Turkey’s Undersecretariat for Defence Industries, the reduction of its external dependency is critical for Turkey’s ongoing defence policy. The report states:

In the next phase [2012-2016 Strategic Plan] SSM aims to reduce external dependence in critical subsystems/ components/technologies determined in line with the requirements of the Turkish Armed Forces. In order to optimize the resources allocated to improve the technological infrastructure needed for the systems projects that involve procurement by means of indigenous local production, and hence increase local content ratio, worthwhile R&D projects have been determined and prioritized in the Defence R&D Road Map. The Road Map consists of R&D Projects that are compatible with the needs and objectives of main system projects, and that strengthen collaboration among the industry, small and medium enterprises, universities and research organizations.[19]

At the crux of Turkey’s drive to grow its military industry is the ruling AKP government’s belief that Turkey cannot be the regional power they wish to become without having an independent deterrent military force.[20] This belief is further illustrated by former Turkish Defence Minister İsmet Yilmaz’s 2013 announcement of a $6 billion investment in a new Research and Development site based in Kazan, which aims to boost innovation and self-sufficiency.[21] Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu recalled Turkey’s “painful experience” during World War I when it was forced to buy arms from abroad, and stated that: “a nation without its own defence industry cannot fight the cause of liberation,” and “by 2023 locally manufactured combat planes will fly the Turkish skies.”[22]

In 2014, Turkey’s defence industry generated $11 billion in orders with overall industry revenue reaching $5.1 billion, a $300 million increase from the previous year.[23] Additionally, Turkey’s defence sector has achieved a 21% annual growth rate over the last five years, with the SSM elucidating the lofty goal of boosting the value of defence exports to $25 billion by 2023.[24] Although, the majority of the growth in the defence sector growth stems from projects within Turkey, domestic consumption is not expected to continue being the growth engine as exports and international cooperation projects will determine the sector’s future growth.[25] The SSM is also targeting future revenue of $8 billion in the defence and aeronautics sectors as the development of several major indigenous military projects, including a Joint Strike Fighter program (TAI TFX Program) and the ATAK helicopter, have already commenced.[26]

As a result of direct government investment in the defence sector, military exports have doubled from $800 million in 2008 to approximately $1.6 billion in 2014; with a projection of almost $2.0 billion by the end of 2015.[27] In the last few years, Turkey’s military exports have steadily rose, creating a positive trend in its ability to capture marketspace in an ever-competitive defence exporting market. In 2014, the United States was the largest purchaser of Turkish defence hardware totalling $508 million in orders, while Malaysia spent $109 million, and the United Arab Emirates spent $87 million.[28] In March 2013, Turkey’s leading armoured vehicle manufacturer, Otokar, won a major $24.6 million contract to supply vehicles to the United Nations (UN), signalling Turkey’s growing importance in the defence sector.[29] Additionally, Saudi Arabia, Azerbaijan, and Oman have expressed interested in the Turkish-produced Altay battle tank, with Oman submitting a bid for 77 tanks in late 2014.[30]

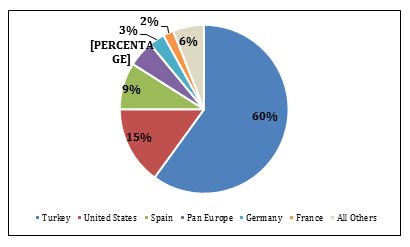

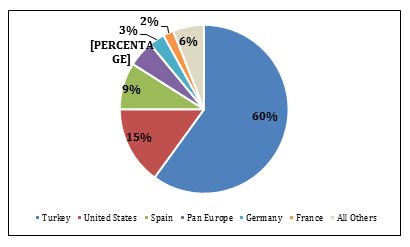

The AKP’s investment into Turkey’s defence sector is married to its overarching foreign policy outlook –neo-Ottomanism– that seeks to position Turkey to become more autonomous and influential on the international stage. To accomplish this goal, Turkish leaders sought to rid its dependency on foreign arms.[31] For example, in 2003, domestic production of armaments was only 25%. Turkey doubled production by 2010, and by 2014, reached 60%. Turkey aims to meet all domestic military need by 2023.[32] Currently, Turkey’s biggest defence importing partner is the United States, which accounts for 15% of all total imports, and Spain is second at 9%. Figure 1 illustrates the primary states Turkey imports its military equipment from:

Figure 1. 2014 Equipment Supply by Country of Final Assembly[33]

With Turkey meeting almost two-thirds of its military requirements domestically, it has made a significant step towards decoupling itself from the influence of the foreign powers that supply its military equipment and a major milestone for the AKP’s policy of military independence.

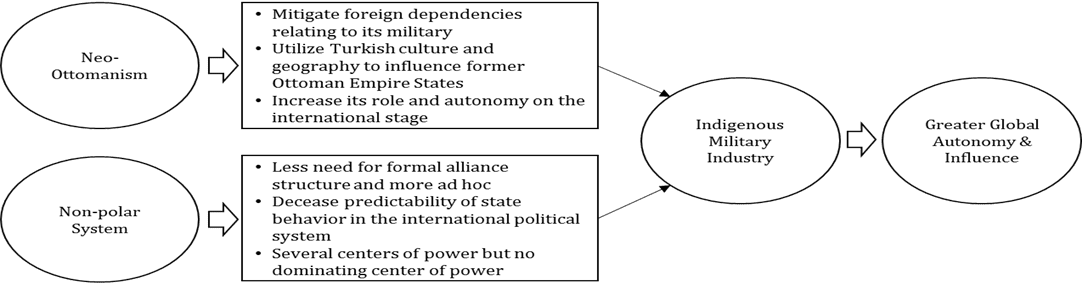

As the AKP’s neo-Ottomanism doctrine continues to drive Turkey’s foreign relations, the continuation of deep investment and growth in Turkey’s defence sector is expected. Figure II outlines several key payoffs that AKP is waging it will receive through an indigenous military industry. Turkey expects that an indigenous military industry will: generate ‘greater international autonomy’ through ridding itself of a dependency on foreign armaments, and thus be able to freely pursue foreign policy objectives. Additionally, an indigenous military industry will create ‘greater international influence’ as Turkey can achieve absolute gains by selling weapons to future clients; especially regional and neighbouring states and non-state actors in the Middle East:

Figure 2. How Turkey’s Military Industry can render strategic gains

The AKP’s sharp vicissitude towards Turkey’s military dependency is well-documented in the literature regarding its commentary towards its defence sector.[34] This attitude has been shaped partially by the constraints that have been placed on the Turkish State to pursue different foreign policy objectives when it conflicted with NATO, and has also left it vulnerable or punished when it did take different course of action. Turkey’s historical dependency on its military AKP’s view on the importance of military independence. The historical record provides a foundation of explanatory power on why Turkey, and in particular, the AKP, are keen on building up its military industry while rebuking its traditional alliance structure.

Turkey’s Historical Military Dependency

Creating a home-grown military industry has been a source of national pride for Turkey’s governing elite. In 2008, then Prime Minister Erdoğan stated that: “we [Turkey] have set as our primary target meeting the requirements of the Turkish Armed Forces from national industry and thus minimizing their dependence on other countries.”[35] Several years later in 2014, during his inaugural address as the newly-elected President of the Turkish Republic, President Erdoğan again spoke about the vast transformation of the Turkish defence industry. He stated that: “Turkey can now manufacture its own tanks, combat ships, attack helicopters, UAVs, communication satellites, its national infantry rifle, rocket launchers, and much other defensive equipment.”[36] The government’s direct policy towards greater military self-reliance is a two-fold initiative that is exogenous of ridding itself of the dependency that has severely constrained Turkey for over a century, while also fulfilling its desire to become more independent and a significant player in the international political system. To provide a contextualization of the importance of the AKP’s outward worldview (neo-Ottomanism) and examination of the century between the present and First World War, will underscore how the Turkish Republic has been arrested by the dynamics of the Eurasian geopolitics, and a state that has been unable to delink itself from the influence of other powers due to its military dependency.

Turkey’s historical dependency on foreign military assistance started in the latter days of the nineteenth century, when the German Empire started investing in the Ottoman Empire (especially railroad and road development) to balance against the United Kingdom.[37] By 1914, and the onset of the First World War, the Ottoman government was under the control of a group of young military officers called the ‘Young Turks,’ and primarily under the direction of Enver Pasha, who later decided to ally with the Central Powers during the war. Although German Officers were instructing Ottoman forces prior to the First World War, soon after the ‘Guns of August’ rang out across Europe, the German Asienkorps along with their Ottoman counterparts, moved towards the British North Africa.[38] To illustrate the level of strategic integration of the Germans in this theatre of war, German Admiral Wilhelm Souchon, who was made a Vice Admiral in the Ottoman navy, and General Liman von Sanders, took command of the newly-created Ottoman Fifth Army and led that army during the British failed Gallipoli Campaign.[39] German officers were heavily integrated within the Ottoman armed forces and had significant influence over war plans and strategy for the first few years of the war. However, by the time of the Russian Revolution in 1917, the cords of discontent were playing between the Germans and their Ottomans counterparts.

By early 1918, Enver Pasha concluded that German and Ottoman goals were no longer compatible after the Russian Empire had collapsed. With the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that ended the war in the East, the Ottoman recouped territory it lost during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), specifically the territories of Ardahan, Kars, and Batumi.[40] Nevertheless, during the negotiations, the Germans did not permit the Ottoman to make any further demands as it conflicted with Germany’s raison d’état, as Martin Sicker describes:

At the peace negotiations with Russia and Brest-Litovsk in 1918, Turkey was prevented from demanding a Russian withdrawal from Erzurum, Trebizond, in eastern Anatolia because the Russians would have demanded reciprocity. This would have entailed a German withdrawal from Russian lands in Europe, something that Germany clearly was unwilling to do.[41]

Similar to the Ottomans being the junior partner with their German allies, a similar situation occurred when the Italians received less than originally promised during the Treaty of Versailles, as they did not obtain their main territorial claims of Fiume (present day Rijeka, Croatia) and Dalmatia.[42] As the Italians and Ottoman’s learned during the First World War, states that are the junior partners in a coalition cannot expect other states to do their bidding for them at the negotiation table; moreover if interests between the two states are not comparable it is highly unlikely that the junior state will get what it wants.

Turkey managed to stay out of the Second World War through the shrewd diplomacy of President İsmet İnönü; however, the calamity that took place throughout Europe, wreaked havoc on the continent’s economy. In response to the growing concerns of the spread of communism, the United States provided economic assistance to the so-called “Frontline States” of Greece and Turkey by January 1947, and to almost every other Western European state soon thereafter.[43] The European Recovery Program (ERP) –or as it is better known, the “Marshall Plan”– was one component in pre-empting any further Soviet encroachment in Europe by moving these states into an alliance against the Soviet Union. However, it was not until August 29, 1949, when the Soviet’s detonated their first atomic bomb that a major push to form deeper ties among Western bloc nations occurred.[44] By 1952, Greece and Turkey joined the original twelve NATO members and were then subsequently folded into its command structure. Given the unique overarching threat of the Cold War, Turkey’s membership in NATO was firmly in their national interests and that of its allies; however, when there was a divergence of micro interests during the détente era, Turkey was once again effected by the leading coalition partner, the United States.

On October 17, 1974, the United States Congress introduced a bill that imposed an arms embargo on the Turkish Republic as it deemed that it had: “substantially violated the 1947 agreement with the United States governing the use of U.S. supplied military equipment” during its military operations in Cyprus the year prior.[45] This event was a watershed moment that altered Turkish thinking on the need to create diversity in its military supply chain, as it was hit hard by the embargo.[46] The embargo had serious consequences for Turkey as it was almost completely dependent on the United States for all of its armed forces supplies. To circumvent the embargo, Turkey petitioned other NATO members, such as the United Kingdom, Italy, France, and especially West Germany, to fill in the supply and financial assistance gap.[47] As tension continued through 1975, Turkey increased its military expenditure and by 1977-1978, almost 30 percent of Turkey’s budget was used on its defence budget.[48] The invasion of Cyprus led to a serious economic crisis in Turkey throughout the middle and late 1970s and remains a pressure point in Western-Turkish relations even today.[49] As this event demonstrates, even an important frontline NATO member during the Cold War can still be at the mercy of the another states if there is a divergence of interests. Although, it was still undoubtedly in Turkey’s raison d’état to remain under the NATO security umbrella until the end of the Cold War, this event sowed the seams of distrust between Turkey and the United States.

With the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989 and the end of the Cold War two years later, Turkey’s significance to the United States and NATO was put into question. With the Executive Branch of the United States government no longer actively lobbying to prevent the Legislative Branch to consider legislation that would reference Turkey’s (Ottoman) ostensible involvement in the Armenian genocide; couple with increasing pressure over Cyprus, and human rights violations pertaining to the Kurds, led to growing concerns among the Turkish elite that Turkey’s place of importance with the United States was fading.[50] This led Turkish officials to seriously discuss a new foreign policy route to establish greater Turkish autonomy in the international political system (neo-Ottomanism of the 1990s).[51] Nonetheless, the years between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the start of the Gulf War also weighed heavily on some Turkish strategists to prove that Turkey was still: “a reliable ally of the west… [and] an indispensable partner for protecting Western interests by overcoming the complicated polices of the Middle East.”[52]

On August 2, 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait and subsequently propelled Turkey back in the ‘frontline’ of international politics. When the Gulf War started in 1991, Turkish President Turgut Özal, in contrast to many others in his own party and in the military establishment (Foreign Minister Bozer, Defence Minister Giray, and General Staff Chief Torumtay all resigned in protest of Özal approach to Iraq), supported the United States’ efforts wholeheartedly, in part to his personnel relationship with President George H.W. Bush. Turkey allowed the use of its airspace to attack targets in Iraq and Kuwait.[53] In return for his support, Özal expected high levels of economic aid from the United States and Gulf states, and although a $4.2 billion defence fund was set-up for Turkey, the embargo imposed on Iraq after the war, and the effects of the war itself, ravaged the Turkish economy in its Southeast as: “the loss of income from the Iraq-Turkey pipeline, large scale disruption of bilateral trade as well as border trade and the unemployment that this caused in south-eastern region, Iraq’s non-payment of its debts to Turkey.”[54]

Although at times Turkey received benefits from its strategic alliances, it also discovered the limitations and constraints imposed by being a junior partner of an alliance; as a result, domestic issues flamed up and in the eyes of many Turks, both in government and regular citizens. Throughout the 1990s, Turkey had a period of economic booms and busts as well as several weak coalition governments that created political and economic instability. In November 2000, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) provided Turkey with an emergency $11.4 billion in loans and Turkey was forced to sell many of its state-owned industries in an effort to balance the budget. Simultaneously, there was large-scale unemployment, a lack of credit, hyperinflation, and tax increases. Efforts to arrest the stress in Turkey’s financial system did not produce any meaningful results and by early 2001, the country was quickly falling into turmoil.[55] By November 2002, an election was held with the moderate Islamic AKP under now President Erdoğan winning by a landslide becoming the Turkey’s first single party government since 1987.[56]

The historical dependencies, as aforementioned, has constrained Turkey’s ability to achieve its national objectives and caused domestic issues. This was discussed when President Erdoğan outlined his government’s strategic vison to mark the 100th anniversary of the Republic, whereby he stated that eliminating military dependencies has been an important component of the government’s plan. One such example occurred on March 16, 2015, when President Erdoğan in a speech at the inauguration ceremony of the newly established Radar and Electronic Warfare Technology Centre –launched by Turkey’s leading state-owned defence system producer, ASELSAN– stated that: “We [Turkey] plan to eliminate external dependency on defence equipment supply with ongoing projects and investments by 2023. We will not allow the use of any ready defence equipment without our being involved from design to production.”[57]

Turkey’s historical dependency is an important component when explaining the government’s current drive to create an indigenous military industry, or its original decision with the now scraped 2011 deal with China’s Precision Machinery Import and Export Cooperation (to co-develop a missile defence system that is incompatible with NATO’s). The historical dependency construct plays a vital role in the framework of the APK’s foreign policy doctrine neo-Ottomanism, as one key goal of that doctrine is to eliminate any foreign dependency on its military. Although, in the international relations literature, this behaviour is often cited as expected state behaviour within the framework of realpolitik; it will still have to be contextualized within a neo-Ottoman foreign policy doctrine that has recalibrated Turkey’s geopolitical orientation and aspirations. This is because creating a self-help component is structurally within the framework of realpolitik. Turkey’s international engagement –its denotation of vital interests and its policies towards other states– under neo-Ottomanism is not always calculated through a pure cost benefit analysis of its raison d’état.[58] Additionally, the rapid change in the polarity (non-polarity) of the international political system, provides further insights into how Turkey has been able to achieve greater international autonomy and influence.

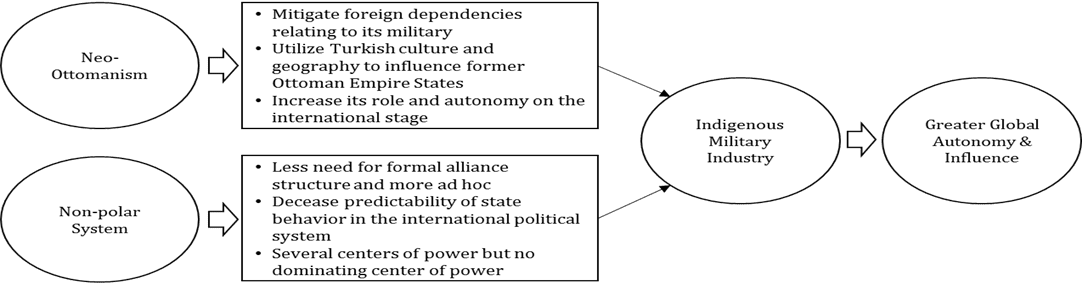

Neo-Ottomanism and Changing Global Polarity

Changing global polarity and neo-Ottomanism are not mutually exclusive in causing Turkey’s drive towards the creation of its indigenous military industry, as these two factors overlap in effecting Turkish geopolitics. As such, these components represent a direct correlation in terms of outputs towards the rationale for creating an indigenous military industry and achieving the AKP’s aspirations of greater global autonomy and influence for Turkey. Therefore, to determine a future state that accounts for this new hard power component being utilised as a political instrument, both the international system and Turkey’s new foreign affairs doctrine will need to be further scrutinised and contextualisation.[59]

Figure 3, outlines at a high level how neo-Ottomanism and non-polarity work in-tandem to drive Turkey towards a final output of great global autonomy and influence through establishing an indigenous military industry:

Figure 3. How both neo-Ottomanism and a non-Polar system facilitates Turkey’s indigenous military industry to achieve greater global autonomy and influence

Creating an indigenous military industry enables Turkey to have a greater role on the international stage influencing other states through military transfers, as well as mitigating the influence of other states by reducing external dependencies of its armed forces. These consequences of having an indigenous military industry are influenced by neo-Ottomanism partial alignment to “structural” realpolitik (yet not to be confounded as pure realism). Non-polarity also influences Turkey’s drive toward greater global influence and autonomy, as the inherent nature of this political system facilitates a diffusion of power, enabling states to independently vie to influence other states. Having a robust exporting military industry in a non-polar world gives states “chips on the table” to play power politics; yet it can also create difficulty in cultivating influence as alliances are less predictable and states can be more susceptible to reserve leverage, as previously discussed.[60]

- Neo-Ottomanism:

Although similar states, such as, Italy, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom –which all have robust military industries– remain firmly entrenched in the so-called “western” alliance structure, Turkey has been rebuking NATO and the west on some issues over the last decade. At the crux of this shift is that unlike those aforesaid states, Turkey has desired a more proactive and augmented position in world affairs.[61] For example, former Turkish President Abdullah Gül stated that: “if you look at all the issues that are of importance to the world today, they [the west] have put Turkey in a rather advantageous position.”[62] This outlook is due in part to its reversal of the historical dependency that has hindered Turkey’s position in the world, but it also stems from a foreign affairs doctrine –neo-Ottomanism– that strives to reorient its geopolitics and views Turkey as a central power with an important regional role that has only recently started to crystalize in practice.

The change from Turkey’s traditional foreign policy doctrine –Kemalism– to neo-Ottomanism has been at the centre of Turkey’s foreign policy shift. Although, Kemalism has been Turkey’s foreign affairs doctrine since the founding of the Turkish Republic by the Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1923 (who had an affinity for French culture from his time spent in in France as a young Ottoman military observer in 1910), the origins of neo-Ottomanism have been sown into Turkey’s social fabric for generations; despite Atatürk’s attempts to universally westernize Turkey during his reforms of the 1920-1930s.[63] In the Kemalist view, Turkey is a “European” state and it should revolve around a “European” axis in foreign affairs. Similar to Peter the Great’s westernization of Russia, Atatürk’s reorientation of Turkey towards Europe has been a pillar of Turkey’s foreign policy orientation most commonly known to Western foreign policy practitioners during the Cold War and the decade after.

When the AKP came to power in 2002, they reaffirmed the Kemalist desire to join Europe –by envisaging to join the European Union, and strenuously strove to accelerate Turkey’s membership bid. However, throughout the early 2000s, negotiations did not progress positively, and the AKP shifted away from a Euro-centric approach with some in the upper echelons of power believing Turkey did not need Europe or that it would never join the E.U. For example, Yiğit Bulut, a senior advisor to President Erdoğan, stated that Turkey has been: “used by Europe and its extensions” and for years, have been “humiliated and scorned” in the process. He continued to say that: “today we don’t need this [E.U.] and the most important thing is that there is no Europe and it is impossible for it to be in the new balance of the world order.”[64] While former the Minister for European Union Affairs, Egemen Bağış, stated that: “In the long run I think Turkey will end up like Norway. We will be at European standards, very closely aligned but not as a member.”[65] As such, Turkey now seeks to become the so-called bridge between the West and the Middle East as well as aims to propagate greater ties and influence in Middle East, North Africa, and in the Somali Peninsula –all former Ottoman Empire states.

At the crux of this policy shift is the fundamental break from the Kemalist ideology and movement towards a neo-Ottomanism policy that has been promulgated by the AKP. This shift has become even more pronounced with the changing power dynamics and polarity of the international political system –increased non-polarity. Although the AKP’s leadership (especially its architect, now Prime Minster Davutoğlu) refer to their foreign policy doctrine as so-called “Strategic Depth,” a continuation of an approach that was started under Turgut Özal during his tenure as President in the early 1990s. In its current context, neo-Ottomanism aggrandizes Turkey’s Ottoman past by promoting the urbane roots and the legacy of the Ottoman Empire to achieve national prestige to rekindle its culture footprint globally.[66] This approach to international affairs does not neatly correlate to any general theory of international relations, but stems from a construct of how Turkey can positon itself geopolitically through its heritage.[67]

Due to a lack of an hard-power component, neo-Ottomanism has been traditionally deployed in a solely soft power capacity, as exemplified by the Somali case, which has often been cited as an engagement to highlight Turkey coming to the aid of a fellow predominantly-Muslim state that was once linked to the Ottoman Empire; yet it seemingly is not does not hold any vital strategic importance for Turkey.[68] A further outlook of what constitutes neo-Ottomanism’s outlook from a soft power and public diplomacy perspective is further explained by Ibrahim Kalın, a chief policy advisor to President Erdoğan, Kalın writes:

Reconnecting with its history and geography, Turkey ascribes strategic value to time and place in a globalized world, and is leaving behind the one-dimensional and reductionist perspectives of the Cold War era. From foreign policy, economy and public policy to education, media, arts and sciences, Turkey’s newly emerging actors position themselves as active players demanding the global transformation of centre-periphery relations in order to create a more democratic and fair world system. Political legitimacy has become an integral part of international relations in the 21st century. It is impossible to implement a policy that does not stand on legitimate grounds in a globalized system. In cases where there is lack of legitimacy, crises are inevitable and the cost is often too high. International public opinion has become a key point of reference for countries to define and implement their foreign policy.[69]

Since a neo-Ottoman doctrine is grounded in the construct of utilizing Turkey’s Ottoman past for its partial international engagement, it is important to underscore that this doctrine does not fall firmly within the framework of realpolitik in terms of its outputs; insofar as, the assumption that Turkey will act solely in its raison d’état with its international diplomacy, it in conflict with broader geopolitical realities or optimal payoffs –usually due to domestic political factors as Kalın pointed out.[70] This aspect of neo-Ottomanism creates a dichotomy with the self-help aspect, which is firmly a principle of realpolitik, within the neo-Ottoman doctrine.[71]

The self-help aspect of neo-Ottomanism is further outlined in now Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu’s amply named book: Stratejik Derinlik, Türkiye’nin Uluslararası Konumu (Strategic Depth, Turkey’s International Position). In Stratejik Derinlik, Davutoğlu grounds his approach with the framework of realpolitik and places a strong emphasis on Turkish autonomy and self-sufficiency.[72] The foundation of Davutoğlu’s theory stipulates that in order to maintain optimal independence, Turkey should not be dependent on any one state and pursue policies that actively find a way to balance its relationships and alliances.[73] Prime Minister Davutoğlu reiterated this claim at a ceremony to mark the 100th anniversary of the Turkish (Ottoman) victory over the Dardanelles, when he emphasized the importance of a national military industry and self-reliance, stating that: “We [Turkey] lost World War I because the Ottoman state did not have its own combat technique… a nation that doesn’t have its own defence industry cannot have a claim to independence.”[74]

Adding to this self-help component of neo-Ottomanism, while also giving attention to Turkey’s pivot away from a solely Western approach of Kemalism, Josh Walker in his review of Prime Minister Davutoğlu’s Stratejik Derinlik, provides further insights into why Turkey is moving away from a Western-centric foreign policy orientation, Walker writes: “Strategic depth as applied to Davutoğlu’s emerging foreign policy agenda seeks to counterbalance Turkey’s dependencies on the West by courting multiple alliances to maintain the balance of power in its region. The premise of this agenda is that Turkey should not be dependent upon any one actor and should actively seek ways to balance its relationships and alliances so that it can maintain optimal independence and leverage on the global and regional stage. This new reading of Turkey’s history differs markedly from the traditional republican narrative that sought to sever all ties with the pre-Republican past and reject all things Ottoman.”[75]

As Walker points out, there is a certain national pride regarding Turkey’s Ottoman past that cuts through different social-cleavages of Turkish society. It is here that realism meets with an important domestic constructivist factor of being predisposed to Muslim countries and former Ottoman states that drives foreign policy within Turkey.[76] Ibrahim Kalın, in a report for the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Centre for Strategic Research (SAM), summaries the break from the full prescriptions of state behaviour under realpolitik, he states: “Turkey [foreign policy] is emerging as a result of a new geopolitical imagination on the one hand, and Turkey’s economic and security-based priorities on the other. The tectonic changes in Turkish foreign policy can be reduced neither to ideological considerations, nor to realpolitik anxieties.”[77]

Therefore, it is essential to underscore that Turkey’s investment in its indigenous military industry initiative fits neatly into part of the narrative of a neo-Ottoman foreign policy doctrine that seeks to rid Turkey of its foreign dependencies, creates further international autonomy, and grows its global influence. It does not, however, drive Turkey’s actual engagement strategy; rather, it enables it to be able to pursue the constructivist elements of neo-Ottomanism –styling itself as the heir to the Ottoman Empire and a protector of Turkic-speaking people across the arc of Central Asia.[78] Alternatively, it is imperative to separate the external goals of neo-Ottomanism and not simply juxtapose it with realpolitik, unless structurally classified in the self-help framework.[79] While similar to soft power, an indigenous military industry is another foreign policy lever, albeit more powerful, that can pull to increase its global influence and autonomy, while concurrently targeting its neighbouring states to predominantly influence.

As a neo-Ottoman foreign policy expands Turkish hard power projection, it will be in an advantageous position to use its military industry to shape the politics of the Middle East by supplying weapons to states without incurring direct costs to its military. Already, reports have alleged that Turkey’s state intelligence agency (Millî İstihbarat Teşkilat) helped deliver arms to parts of Syria under Islamist rebel control from early 2014 into 2015.[80] With this contextualization of neo-Ottomanism in Turkish foreign policy, coupled with its break from Kemalism, Turkey is on a new foreign policy course and has a new hard-power component enabling it to continue to pursue the constructs of its foreign policy doctrine. Currently, with the emergence of new regional powers and the relative decline of West, Turkey also has additional space to operate within a less rigid political system as the age of non-polarity starts to grip in the international political system.

- Changing Global Polarity

As the ground shifted in Turkey, it was also shifting globally. Over the last 30 years, the polarity of the international political system has transitioned three times: From the Soviet-American bipolar system of the Cold War, to the American “unipolar moment” during the disintegration of the Soviet Union, to the contemporary emergence of the age of non-polarity. The age of non-polarity has fostered a new allocation of power throughout the international political system with ever increasing competition for influence.[81] From tension in Southeast Asia over Spratly Islands, to Ukraine’s tug of war between Moscow and Brussels, to Saudi Arabia and Iran’s proxy war over Yemen, the international system has become more crowded with major players at the regional level. This has facilitated more competition amongst states geopolitically and has steadily changed how the international system operates and even puts into question how alliances are formed, maintained, and if they can remain predictable.

Unlike a multi-polar system, an important feature of non-polar world is there are many more power centres (regional powers versus classic great power balancing), and quite a few of these centres are also non-state actors. In other words, the primacy of the nation-state is not paramount in a non-polar world, and the system itself is more ad hoc and transaction with more of a regional diffusion of power. This does not mean that nation-state no-longer matters, but Richard Haass outlines the framework of a non-polar world in The Age of Nonpolarity, explains that the traditional alliance structures governing state relations since the end of the Second World War are no longer a relevant understanding of the current international system. He further explains that the relationships between states are becoming more selective and transactional:

Non-polarity complicates diplomacy. A nonpolar world not only involves more actors but also lacks the more predictable fixed structures and relationships that tend to define worlds of uni-polarity, bipolarity, or multi-polarity. Alliances, in particular, will lose much of their importance, if only because alliances require predictable threats, outlooks, and obligations, all of which are likely to be in short supply in a nonpolar world. Relationships will instead become more selective and situational. It will become harder to classify other countries as either allies or adversaries; they will cooperate on some issues and resist on others.[82]

Besides greater unpredictability of alliances, a non-polar system is also less rigid when compared to a system of uni-polarity, bi-polarity, or multi-polarity. This is because non-polarity has numerous centres of meaningful power, yet no dominating centre.[83] For Haass, there is a diffusion of power that goes beyond a state or a superpower, and power is also allocated to multi-national organizations and non-state actors, for example.[84] A non-polar world, in summary, is a complex and messy international system and one where: “leading powers lead, albeit in consultation and cooperation with (and their interests taken into account) second tier actors, however fluid and issue-specific the coalitions may be.”[85]

Turkey’s efforts to adapt to the emerging geopolitical configuration of a non-polar world is also a factor in driving Turkey towards an indigenous military industry, as it needs a self-help mechanism to protect itself from growing global uncertainly as well as a mechanism to influence other states beyond its traditional utilization of Soft Power. As a result, the age of non-polarity is driving Turkey towards an indigenous military industry in two distinct ways. First, since the international system is a less rigid system, there is more flexibility for Turkey to take a divergent foreign policy path from its NATO alliance structure. This does not equate carte blanche when dealing with its ‘partners,’ but given that a neo-Ottoman foreign policy doctrine seeks to alter Turkey’s geopolitical augmentation, it overlaps with a system that is inherently more conducive to power shifts and creates a window to actively alter the conditions it interfaces with the west.[86] As a result, Turkey understood that a “chip on the table” is required to play the game of great power politics beyond Soft Power to achieve greater global influence and autonomy.[87] Second, an indigenous military industry provides Turkey with a self-help framework that bolsters its own security in a world that alliances are less predictable and more uncertain.

Turkey has already shown its willingness to pursue an independent foreign policy objective against the position of a superpower. One example is through its 2008 invasion into northern Iraq, which went against the United States position.[88] Turkey was able to perform this military action due in part to a system that has a strategic calculus which goes behind a binary “do or don’t” expectation that sometimes gripped the bi-polar Cold War system. In the age of non-polarity, if a state achieved enough influence or removed foreign leverage (having chips on the table), it can successfully navigate between great powers and superpowers to achieve its desired outcomes, or it can pursue policies that go against an “allied state” more easily, as recurrent cooperation of an alliance system is no-longer expected.[89] For example, Turkey’s decision to assist different rebel groups in Syria than the United States, while Russia bolstered the Bashar al-Assad regime, highlights how a regional power can operate more overtly and unilaterally in a system so long as it has the desire and power to make a credible challenge, and the need for other transactions further down the line.[90]

Alternatively, the creation of a military industry, ensures state security through a self-help framework, as it is also an expected state behaviour under the perceptions of realpolitik and is structurally occurring due to the influence of non-polarity. This is a structural occurrence given that Turkey is feeling less secured in a non-polar world due to increased volatility and instability of the international political system. As such, alliances are becoming less predictable and relations are conducted on more of an ad hoc basis. As Özgür Ünlühisarcikli of the German Marshall Fund, states: “during the last three years and I think it is a result of the destabilization along Turkey’s borders… [It] is feeling less secure.”[91] As discussed, the external goals of neo-Ottomanism should not be confounded of Turkey acting strictly under perceptions of realpolitik. This structural occurrence under non-polarity provides further rationale of Turkey’s drive towards an indigenous military industry under a self-help framework that is system driven, but also correlates with a neo-Ottoman outlook.

Kenneth Waltz’s describes his self-help framework in his book: Theory of International Relations. He writes: “States do not willingly place themselves in situations of increased dependence. In a self-help system, considerations of security subordinate economic gain to political interest.”[92] Watlz’s assessment provides two important insights into how the system is also moving Turkey towards its military industry. First, security is the leading concern of a state in an anarchical world and the payoff received for being independent in this matter are the highest, as survival is at stake. Second, states can receive payoffs from increasing their hard-power to influence other states, this is simply the receiving outputs of the payoffs of reversing Waltz’s self-help framework by creating a dependency or a need on another state. Given that a non-polar world is more ad hoc, Turkey is adjusting to this world through developing further hard-power capabilities.[93]

Both neo-Ottomanism and non-polarity are contributing to Turkey’s drive towards an indigenous military industry –an industry that has the potential to become an important mechanism in statecraft, mitigating the influence of foreign powers and projecting over other states. By being less constrained, states are theoretically able to pursue policies that will achieve relative gains and have the latitude to directly pursue objectives that might diverge from a traditional alliance structure. As such, the “future” of Turkish foreign policy and its ability to utilize a military industry as a political instrument is predicated upon: the longevity of the non-polar system, neo-Ottomanism, and sustained economic and political continuity, as Turkey is guided by a new grand strategy in international affairs that seeks greater international autonomy and influence. With this collective narrative on the prime factors driving the Turkish state from both a domestic and systematic view, this paper will now hypothesize what is the “future state” of Turkish foreign policy with an indigenous military industry.

Turkish Foreign Policy with an Indigenous Military Industry

The contextualization of neo-Ottomanism, the shift in the polarity of the international political system, and the effects of Turkey’s historical dependency on foreign arms, are all vital factors in establishing a hypothesis of the “future state” of Turkish foreign policy that accounts for an indigenous military industry. This collective narrative of the following two observations, then provides an overarching theorem of how Turkey is expected to behave in the international arena that calculates for how this military industry will be utilized as a political instrument:

- Hypothesis #1: Turkey will continue to invest in its military industry as it makes for good domestic politics; boosting support for a neo-Ottoman foreign doctrine that will guide Turkey’s international engagement.

- Hypothesis #2: Continued investment in a military industry makes Turkey more self-sufficient; resulting in its ability to pursue an autonomous foreign policy that defects from NATO’s policy positions when interests diverge.

These observations are not mutually exclusive of one another, as both have to occur in order to establish a singular hypothesis that predicts: how the establishment of an indigenous military industry is part of Turkey’s purposeful plan to pursue an independent foreign policy that is less constrained and beholden toward any specific geopolitical orientation; especially one centred around NATO, Europe, and the United States, as Turkey aspires to be recognized as an independent and influential global player on the international stage. These observations converge into one hypothesis that describes an understanding of what future effects of a future indigenous military industry will have on Turkish foreign policy that accounts military industry.

- Hypothesis #1

The inputs of public opinion on foreign policy should not be discounted as a secondary factor in the political calculus of a state.[94] In most forms of government, and especially in democratic societies, domestic politics can be a significant contributing factor in a state’s ability to conduct foreign affairs –even during instances that seem to be counterproductive to their own national interest.[95] This is because national leaders are accountable to public opinion and at times are placed in difficult positions by the behaviour of their citizens. This was illustrated by Turkey’s recent clash with China over the situation pertaining to its Muslim Uighur populace, as well as the 2010 Mavi Marmara incident (Gaza flotilla raid).[96] As the 2014 Kobane crisis has shown, elections, public opinion, and other domestic factors can drive foreign affairs.[97]

There is a robust body of literature pertaining to the actual impact of domestic politics on foreign affairs and vice-versa. The crux to understanding the future implications of Turkey’s military industry is through a determination of domestic support for policy continuation, insofar as sustained domestic support for the AKP government equates a continued neo-Ottoman foreign doctrine, which in-turn dictates Turkey’s international engagement. The assumption that domestic politics effects international relations is important to examine both through the perspective of public opinion outputs: the view of the public pertaining to a specific country or organization that effects foreign relations, and the perspective of public opinion inputs: the view of the public pertaining to a set of politics that are domestically focused but influenced by foreign affairs.

Public opinion inputs regarding Turkey’s defence sector first took the place of primacy as an important policy position by the APK government during the 2011 parliamentary elections. In the weeks leading up to that election, the Turkish pressed covered how the APK focused on the defence industry at campaign rallies:

Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party, or AKP, is putting an unprecedented emphasis on the defence industry in its campaign for the June 12 elections. The party’s promises focus on establishing and developing a domestic industry that comes near to being self-sufficient. PM Recep Tayyip Erdoğan says the capital city of Ankara will become the headquarters of the sector…Visions for the defence industry have not played a key role in election campaigns by either a ruling or opposition party ahead of previous Turkish polls. But this year, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been holding up Turkey’s developing national defence industry as one of the pillars of a modern economy in the 2020s. In the weeks leading up to the nationwide parliamentary election that will be held June 12, Erdoğan had made three major speeches on the national defence industry.[98]

The AKP won the 2011 elections with 49.83% of the vote, a 3.25% increase from the 2007 general election, thus affirming domestic support for AKP policies.[99] This support was cemented when the AKP won the next election cycle in November 2015, as it was once again given a full mandate to govern for another four-years.[100] During his election campaign Prime Minister Davutoğlu “often pledged that his government would give a full go-ahead to Turkey’s indigenous weapons systems programs, including drones, a dual-use regional jet, submarines, frigates, a new generation tank and even a fighter jet.”[101]

Further adding to the domestic support for a stronger Turkey is public opinion surrounding Turkey’s position in world affairs. An October 2015 Research Centre poll found that: “people in Turkey think that their country should garner more respect around the world than it currently does. In all, 54% of Turks say they deserve more respect compared with the 36% who think Turkey is as respected as it should be.”[102] As the military industry can serve as a catalyst for greater international prestige, investment in the defence sector makes for good domestic politics, especially when coupled with neo-Ottomanism. Given that Turkey’s growing defence sector is an established policy preference of the AKP, there is an inordinate unlikelihood that the ruling government will defect from this policy position, as it is both domestically popular and something they are spearheading. Other political parties are at risk of punishment if they choose to defect on this issue, as the AKP can paint the opposition as appearing weak on defence or on the economy that is supplemented by a robust defence sector, or bandwagoning with the west and NATO in the realm of foreign policy.[103]

Domestic opinion and its influence on a leader’s international engagement, as well as being a coalition partner with a highly unpopular country and its policies, can be domestically punishing for a democratic leader. For example, the 2003 Spanish, 2006 Italian, and 2010 Dutch elections, all saw incumbent governments collapse and lose the subsequent election due in part to supporting the United States wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, respectively.[104] Public opinion can shape a leader’s policy, as costs are incurred for following a domestically unpopular policy, such as, falling back to a solely Western foreign policy orientation, providing that he or she makes any substantial change in Turkey’s military sector investment to become more dependent on the west.[105]

While there is low public confidence for NATO in Turkey, another Pew poll found that: “Turks are hesitant to live up to their Article 5 obligation to come to the aid of another NATO country if it is attacked. Nearly half (47%) say Turkey should not use military force to defend a NATO ally if Russia got into a serious military conflict with that country.”[106] With over half the Turkish public believing Turkey should have more global influence; coupled with an increasingly deteriorating perception of NATO, Turkish leaders will be harder pressed to cooperate or appear taking a back seat in foreign affairs. As a result, its growing military sector has become an important source of national pride, while military independence has become a central policy position of the APK and “another side of Turkey’s rise” in the Middle East.[107]

The staying power of sustained investment in an indigenous military industry is vital for an understanding of the future state of Turkish foreign affairs. Through the establishment of a self-help framework that is supported by neo-Ottomanism polices and reinforced by historical experiences, the effects of a more unpredictable international system are being driven by non-polarity and public opinion concerns. As such, there are structural, international, and domestic drivers that provide compelling evidence that Turkish investment in its military industry will not wane. Therefore, it is expected that Turkish investment in its military industry will be stay constant until the APK achieve its goal of total military independence from foreign arms by 2023.

- Hypothesis #2

As discussed in the introduction, “hard power is not the sole variable that governs a state’s ability to project power or to conduct statecraft;” yet “a military dependency, like all dependencies, places a constraint on a state’s capacity to independently conduct statecraft.” As such, Turkey’s defence sector has a utility function for achieving its aspirations of being a global power, and also further emboldens its pursuit of neo-Ottoman objectives. Through both military aid or weapon transfers and the curtailment of domestic military need, Turkey’s defence sector gives it the ability to play the game of power politics and pursue a more autonomous foreign policy from that of NATO. While domestic support for counterbalancing outside influence underpins this trends continuity.

As Turkey closes in on its 2023 goal of becoming entirely self-sufficient on its defence sector to meet its military needs, it will have eliminated a powerful mechanism by which it can be influenced by other states, especially western powers. As a result, Turkey has the ability to distance itself from NATO to pursue a more autonomous foreign policy when its interests diverge from those powers. Additionally, due to non-polarity, Turkey can also seek more transactional cooperation with non-NATO powers in order to achieve absolute gains against those powers when opportunities arise.[108] However, it is important to not confound increased autonomy with the belief that Turkey will leave NATO, but rather that the strategic calculus and conditions under which it seeks to cooperate with NATO has and will continue to evolve.

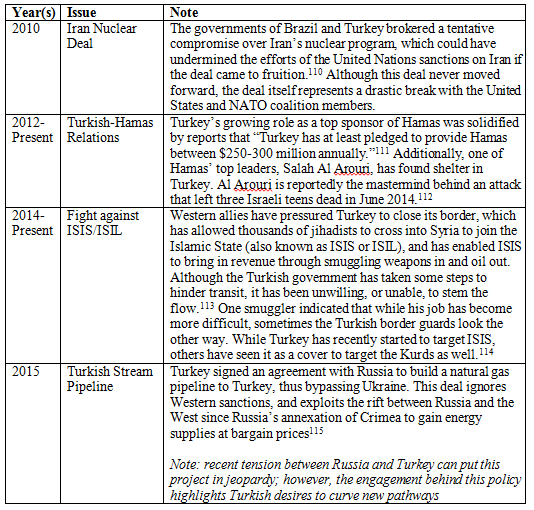

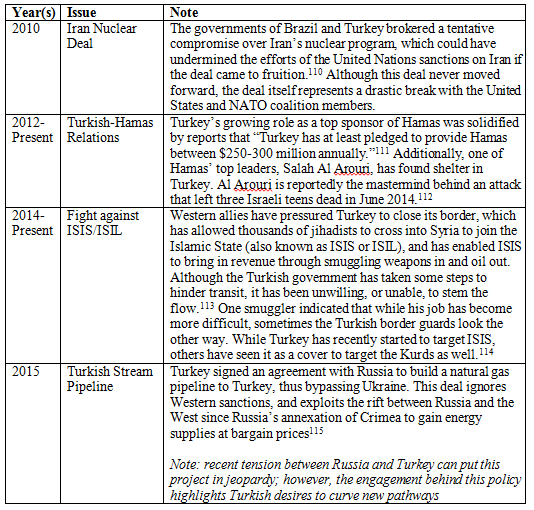

Turkey’s policies related to the arming of non-moderate Islamic rebels in Syria (such as Jabhat al-Nusra), the tentative deal with China pertaining to Turkey’s missile shield, and even its small quarrel over the appointment of former Danish Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen to Secretary General of NATO in 2009, have shown its willingness to rebuke preferred NATO positions.[109] On several occasions, Turkey has also signalled its willingness to cooperate and work with states other than its traditional western partners (See Table 1)

Table 1. Turkey’s Political Conflict with the West

While Turkey’s defence sector affords it the ability to pursue an autonomous foreign policy, western policy practitioners will need to be more in-tune to the micro and macro changes of its relationship, determine areas of common interests, and be selective with those areas to cooperate with Turkey. For example, James Clapper, the U.S. Director of National Intelligence, told the U.S. Congress he was not optimistic that Turkey would do more against ISIS because it had “other priorities and other interests.”[116] As the policies of neo-Ottomanism are further expounded and obtainable through military independence, it creates a higher probability of Turkey diverging from NATO; yet that does not mean Turkey is leaving NATO.[117]

Until a critical mass of leverage is established upon other states or influential non-state actors, Turkey is limited in its ability to achieve its neo-Ottoman objectives, and can in conflict with the United States and NATO’s when common interests diverge. As shown, Turkey’s foreign policy movements since the Arab Awakening proved its engagement preference of trying to cultivate greater global autonomy and influence.[118] Therefore, through the utilization of its military industry as a political instrument, Turkey can generate leverage to influence other states through military aid or weapons transfers.

- An Indigenous Military Industry utilized as a Political Instrument

To understand how hard power will be utilized, first it is necessary to understand why it is needed over soft power. As mentioned, Turkey has relied on its soft power to achieve greater global influence and power. Turkey’s first attempt to generate greater influence was at an apropos moment for soft power during the Arab Awakening, when the Middle East saw many dictatorial governments collapse or be overthrown. In the power vacuum that followed, Turkey went on a Soft Power offensive to cultivate influence in those states; especially Prime Minster Erdoğan, who travelled to Tunisia and Egypt and throughout the Middle East to drum up support from the less secular and more religious segment of the countries that were suppressed.[119] This led to an increase of influence and prestige for the Turkish state, thrusting them into the frontline of international politics, as Turkey was hailed as the model of democracy in the Middle East.[120]

By mid-2011, the Arab Awakening subsided and caught many Turkish policymakers by surprise.[121] Turkey thought that the regime of Bashar al-Assad would quickly collapse; yet he has since managed to hang onto power, causing a quagmire. In other cases, the old regimes have returned in to power in the Middle East. As a result, Turkey did not adjust its geopolitical position and lost much of its influence with those states, and has become increasingly isolated in the current geopolitics of the Middle East.[122] Turkey’s overt subversion in the domestic affairs of some states and outward hostility to the new regimes, have made rapprochement difficult, and has significantly diminished its own influence and soft power in the process.[123] A clear example of this is the case in Egypt, where Turkish-Egyptian relations went from robust cooperation to opposing political tit-for-tat moves.

Upon the ousting of former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak in 2011, Turkey heavily supported the democratically-elected Muslim Brotherhood government led by Mohamed Morsi, resulting in a “honeymoon” period of cooperation and trade in Turkish-Egyptian relations. Relations between the two states were growing until Morsi was usurped in a military coup d’état by Egypt’s current President, General Abdel el-Sisi in 2011. Instead of trying to make new bedfellows with the new regime in Cairo, President Erdoğan went on the offensive and publicly attacked President el-Sisi domestically and at the United Nations citing Morsi’s ouster as unlawful.[124] As a result, President el-Sisi’s administration decided to cancel the important “Ro-Ro” agreement with Turkey (signed during President Morsi’s reign), effectivity blocking it from transporting containers to the Gulf via Egyptian ports, and also spearheaded a successful campaign against Turkey’s bid for a rotating Security Council seat on the United Nation’s Security Council.[125]

A similar case occurred in Tunisia, when Turkey heavily supported the Ennahda Movement, but influence was again diminished when the Ennahda government stepped aside so a national unity government could be formed to redesign the Tunisian constitution.[126] As a result of failing to maintain its influence during the aftermath of Arab Awakening, Turkey has since become isolated in the Middle East. This has occurred due to increased regime change as shown by Egypt and Tunisia, or in anarchy-gripped states, such as Libya and Syria, Turkey is having trouble inserting influence over different competing factions as other global powers are engaged in a micro proxy wars.[127] Regardless, if Turkey’s isolation is either temporary or systemic, Turkey learned two important lessons. First, the staying power of soft power is limited and its reach occurs if they can work with likeminded governments. Second, the outcome of those proxy or over-turning the status quo requires hard power leverage.[128]

Given the driving force of neo-Ottomanism and its ambition both domestically and at the governmental level, it is unlikely that it will detour from pursing its goal of greater global and autonomy. As such, barring any regime change, Turkey’s only chess piece to move to cultivate regional influence is through coercive diplomacy, and therefore, a future state of foreign policy is predicated upon its ability to target states or non-state actors that have no other place to turn to or are looking for a new partner. This creates the risk of Turkey being leveraged by other states or actors that can temporary bandwagon for short-term gains, because it has not yet created a critical mass of weapon exports to any particular state, and would not be able to receive transfers from another state. In other words, Turkey does not have a “paternalism” over another state, but as Turkish ambition grows in parallel with its military industry, this dynamic may also change.

Turkey has the latitude to enter into a new age of statecraft –also aided by the change in the international political systems due to the era of non-polarity– where it can leverage its hard power means to derive payoffs to garner great international autonomy and influence. Since military or interior affairs does not only govern a state’s ability to protect its citizens (or control), it is also a mechanism by which one state can influence another state vis-à-vis coercive diplomacy. Therefore, to understand how Turkey can use its military industry to gain influence, it is important to first qualify how military transfers equate geopolitical payoffs and influence.

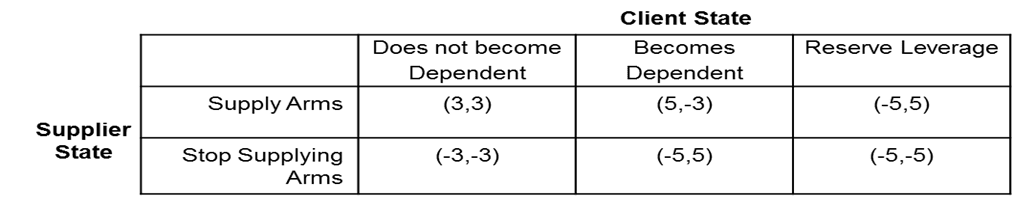

Coercive influence could be utilized in a multitude of ways, but it is most often deployed through deterrence, compellence, or direct violence. However, only corpulence and deterrence will be assumed as the underlying mechanism to understand how a military industry, specifically Turkey’s, can be utilized to forge successful, coercive diplomacy. Often cited by Carl Von Clausewitz puts it: “war [is] a continuation of politics by other [violent] means,” and therefore no longer coercive in an ad bellem situation where a state can exercise influence through military transfers.[129] Unlike deterrence, compellence shifts the initiative of the first action to the coercer and will subsequently affect an opposing leader’s decision tree. For example, in a hostage situation, compellence involves the police threatening a suspect with death if he or she does not surrender; while deterrence is what should have prevented an offender from taking any hostages in the first place. Both compellence and deterrence are underpinned by the credibility of the coercer.[130] Therefore, if a state is dependent on another state for military supplies, then that state is susceptible to coercion by the state that supplies its weapons. Adversely, a state that has a dependency cannot issue a threat without any credibility behind it, because another state is aware of this dependency. As a result, a state will then have to evaluate whether or not the ramifications for defecting would be too costly before acting.

Another important component of effective coercive diplomacy is decrypting the actual gains of the influence that military aid generates. This analysis requires an understanding of what are the potential pitfalls or benefits of giving and receiving military aid. There is clear empirical evidence regarding the importance of military aid and its impact upon recipient states, yet there is also a false assumption that the state giving aid also benefits. For example, the United States deployment of military aid directly after the September 11th attacks, was both beneficial and detrimental. Providing military aid to the former Soviet Republic of Georgia had clear benefits, in that, the United States had an ally in former President Mikheil Saakashvili: he committed 2,000 soldiers to support the U.S. war effort in Iraq.[131] However, in the case of Pakistan, the United States gave billions of dollars in military aid, which in turn, was funnelled to extremist groups, including the very same Haqqani network and Taliban militants who are killing U.S. soldiers fighting in Afghanistan.[132]

Although both aforesaid states received generous military aid, the United States expected to gain influence in both states; however, failed to recognize the differences between the two state’s own internal objectives and international position. In the case of Georgia, they viewed Russia as a major outside threat and needed a powerful ally to ensure their own security and state survival. Additionally, most of the Georgian military makeup prior to American security cooperation were outdated Soviet equipment, which made them especially vulnerable to Russian influence.[133] In the case of Pakistan, although they are in direct competition with India and feel internally threaten by the Indian state, they are also a nuclear power and not threatened directly by the Taliban in a traditional war situation.[134] This military aid was mostly not deployed by Pakistan against America’s foe –the Taliban– but used to counterbalance against India’s growing military power.[135] Second, Pakistan’s long-standing policy of destabilizing Afghanistan and having close ties to the Taliban, did not correlate with American interests.[136] The situation of U.S. aid to Pakistan is a textbook case of the Reverse Leverage model, where rather than inducing compliance, generous U.S. military funding created a strong client state who was able to ignore U.S. interests and play the U.S. off against other powers.[137] In effect, Pakistan understood that the United States wanted to influence them and allowed that perception to continue.[138]

In the Turkish case, the same concepts and lessons also apply as it has started to carve out an autonomous foreign policy. Given that neo-Ottomanism is a socially constructed policy, Turkey is also more susceptible to potentially falling into a reserve leverage situation, as it will seek to build coalitions that are not always associated with its raison d’état; insofar supporting a group or state that is closer to its own non-secular ideology over other regimes (as demonstrated through its action during and after the so-called “Arab Awakening”). A second example is the arming of Syrian rebels considered to be too extreme for the United States and other NATO allies.[139] This situation gave Turkey the opportunity to reap payoffs if rebels were successful in overthrowing the Syrian government; but instead has created a situation of being drawn into a reverse leverage situation, where it has lost influence to Russia and the United States. Through supporting some rebels over others and working outside the scope of other major powers, Turkey has painted itself into a corner, as Russia increases involvement in bolstering the Bashar al-Assad regime and the United States ends their aid to rebels. Turkey is left isolated and only influential over a marginalized group and has no other choice but to support the rebels, as it has no other prospect of influencing other stakeholders at this point in time.[140]

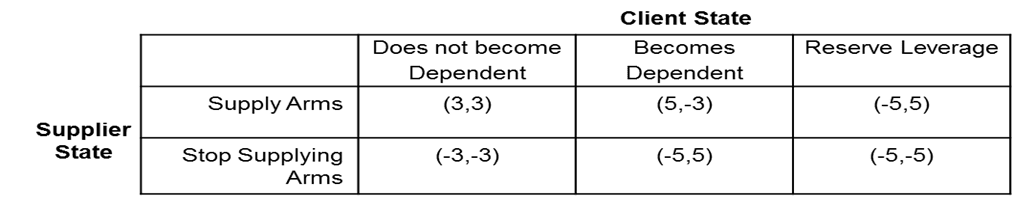

The potential payoffs stemming from Turkey’s military industry is dependent upon how far a dependency can grow. In this regard, there are several payoff or punishment scenarios that are predicated upon if an opposing actor either believes they need Turkey (as they do not have any other partners to turn to), or believe they can play Turkey off another state to reap further rewards. The payoff matrix below highlights what Turkey can expect in terms of payoff or punishment on arms transfers as a part of its foreign policy initiatives. The matrix is denoted through a logical game structure. For example, if Turkey supplies arms to a state, it receives the payoffs of both influence and return on investment, while if the recipient state does not become dependent, it still receives what it wants. If the state becomes dependent to a supplier state, then that state receives a greater payoff, as it can exercise greater influence, while the client state can be swayed more easily by the supplier state. If the client state realizes its dependency and seeks to counterbalance by finding a new supplier state, the supplier state loses its influence and leverage.

Table 2. Payoff Matrix on Arm Transfers

As shown by this illustrative payoff matrix, Turkey, similar to other states, has to determine the context and conditions for utilizing its indigenous military industry as a political instrument. As such, the balance of how Turkey can garner regional influence is asymmetrical rather than a linear progression.

Conclusion

Given the principles and popularity of neo-Ottomanism, Turkey could possibility be a supplier to a future Palestinian state or non-state actors fighting against Middle Eastern regimes, such as in Syria, Yemen, and Iraq, for example. Yet, it will have to choose wisely so it is not trapped into one side, as a zero-sum game will dictate the policy and any leverage or influence generated will be nullified. As covered, neo-Ottomanism is a doctrine that is not always based in realpolitik and thus is susceptible constructs of creating a sphere of influence with former states of the Ottoman Empire. With Turkey currently marginalized in the international system, coupled with its failure to utilize soft power gains, there is evidence that Turkey will use its military industry to garner influence; however, more research is needed to fully calculate the scope of this political phenomenon.

Over the last five years, Turkey’s defence sector has doubled in revenue, a plethora of new projects are being launched, while other projects are being deployed. This coincides with Turkey meeting almost a two-third of military needs domestically and on track to meet all of its military needs by 2023. As a result, Turkey has rid itself of an import influencing lever of the West, and has become self-reliant in regards to its military need. Additionally, its defence sector is penetrating international markets and has gained modest headway in some sectors. However, Turkey has yet been able to create enough influence or leverage over other states through military assistance or military weapon transfers, and it remains to be unseen if it can establish such a dependency. What is known is that staying power of this charted course in international relations is underpinned by the domestic attitudes which further pushes Turkey in this direction. As a result, the popularity of neo-Ottomanism will produce continued and sustained investment in a defence sector, as it makes for good domestic politics and a mechanism to tap into Turkish nationalism. Therefore, the staying power of an indigenous military is most likely going to occur, and will have lingering ramifications for the Middle East and for NATO.