By Gareth Jenkins

Tuesday, July 1, 2008

Early on the morning of July 1, the Turkish police detained 24 hard-line secularists during a series of raids in Ankara and Istanbul. Those taken into custody included retired General Sener Eruygur, the former commander of the Turkish Gendarmerie; retired General Hursit Tolon, the former commander of the First Army; Sinan Aygun, the head of the Ankara Chamber of Commerce; and Mustafa Balbay, the Ankara representative of Cumhuriyet daily newspaper (NTV, CNNTurk, July 1).

The Turkish media reported that several of the arrests came during police raids on offices belonging to the Association for Ataturkist Thought (ADD), a secularist NGO that was founded in 1989 to promote the ideals of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk (1881-1938), who founded the modern Turkish republic in 1923. The ADD is currently headed by General Eruygur. In the spring of 2007, the ADD was one of the main organizers of a series of mass public protests in which hundreds of thousands of secular Turks took to the streets in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to prevent the ruling Justice and Development party (AKP) from appointing Abdullah Gul as the country’s president.

It is thought that those taken into custody on July 1 are being held on suspicion of links to a shadowy Turkish ultranationalist group known as Ergenekon (see Terrorism Focus, January 29). The group first came to public attention in June 2007, when the Turkish police discovered 27 hand grenades and a small quantity of explosives in a house in the Istanbul suburb of Umraniye. Subsequent investigations eventually led to the arrest in January of retired Gendarmerie General Veli Kucuk, the alleged founder and leader of Ergenekon, and 12 associates.

During the 1990s in particular, General Kucuk was heavily involved in operations, mostly targeting members and supporters of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), conducted by the network of covert groups and organizations known collectively in Turkish as the derin devlet or “deep state.” Kucuk retired from active service in 2000. He later turned his attention to the threat he believed the AKP posed to the principle of secularism enshrined in the Turkish constitution as one of the defining characteristics of the Turkish republic. Documents leaked to the Turkish media suggest that Ergenekon planned to conduct a campaign of violence to destabilize the AKP government and perhaps trigger a military coup.

Ergenekon has been a gift to the AKP and its supporters in the Islamist media, who have used Kucuk’s presence to try to portray the group as being controlled by the Turkish military. Even though Ergenekon was unraveled before it could launch its campaign of violence, it has also been used by Turkish Islamists to bolster a tendency toward denial and willful ignorance when it comes to violence staged in the name of Islam. Since the arrests in January, the Islamist press has regaled its readers with a string of revelations quoting unidentified sources as attributing nearly every recent act of Islamist violence in Turkey to Ergenekon.

In truth, Ergenekon appears to have been mostly composed of “deep state” has-beens and wannabes. Despite the presence of experienced covert operatives such as Kucuk, it was very shoddily organized with little attention given to even the most basic tradecraft. There is no doubt that serving and retired members of the Turkish military were personally acquainted with Kucuk. It is even possible that some individuals were aware that he was organizing something and were sympathetic to his aims. But there is no evidence to suggest that the Turkish military was behind Ergenekon. Indeed, it is likely that, if one of the most powerful and best equipped militaries in the region–and one with a long history of covert operations–were to attempt to mastermind a violent campaign to destabilize a civilian government, it would have armed its operatives with something more effective than a single crate of grenades.

Nevertheless, the AKP-controlled Interior Ministry, which is responsible for police operations, has devoted considerable resources to the Ergenekon investigation in the apparent hope of discrediting the staunchly secularist Turkish military. The Turkish authorities have traditionally been reluctant to use any designation that could be interpreted as implicitly associating Islam with terrorism. As a result, both violent Islamist organizations and potentially violent secularist groups are described as “rightist” and fall within the remit of the same department in the anti-terrorism branch of the Turkish police. Over the last six months in particular, the Interior Ministry has been diverting so many resources to the Ergenekon investigation that members of the “rightist” department in the police are now having difficulty monitoring much more dangerous violent Islamist groups.

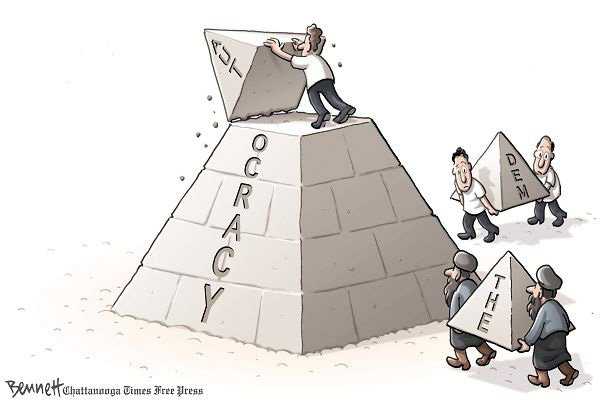

The detentions of July 1 will further strengthen the impression among many secularists in Turkey that the AKP is more concerned with its ideological struggle against hard-line secularists than with law and order. Even if Eruygur and Tolon are subsequently proved to have been linked to Ergenekon, no one seriously imagines that they posed an imminent danger to public security. Most extraordinarily, the detentions came only hours before Public Prosecutor Abdurrahman Yalcinkaya was due to deliver his final presentation in the ongoing case before the Constitutional Court for the closure of the AKP (see EDM, March 17). The detentions will probably be seized upon by the AKP media to try to bolster the AKP’s democratic credentials; but for many others, they will merely reinforce doubts about the AKP’s interpretation of democracy. At a time when the Turkish economy is already looking increasingly fragile, it is difficult to understand why, even if there were evidence against those taken into custody, the Interior Ministry would conduct the raids on a day when Turkish markets were going to be highly vulnerable to any suggestion of an escalation in tension. Not surprisingly, the Turkish financial markets went into freefall as soon as the news of the detentions broke.

The Turkish media reported that both Eruygur and Tolon were seized from the military lodgings where, not least for security reasons, most high-ranking military personnel live after retirement. Whatever motive the Interior Ministry may have had, there is no doubt that the vast majority of the Turkish officer corps will regard the timing and manner of the detentions as a direct invitation to a trial of strength. It is not a challenge that is likely to be ignored. Even if the AKP eventually wins, which is not a foregone conclusion, the price in terms of social and political stability could be very high.