The Ergenekon case is the latest salvo in the battle between the ruling AKP and the nationalist old guard.

By Mustafa Akyol | NEWSWEEK

Jul 21, 2008 Issue

Things are getting very hot this summer in Turkey—and it’s not just the weather. A long-simmering constitutional crisis is boiling over, and the country is experiencing one of its most turbulent periods in decades. Over the past several weeks, Turkish authorities have arrested two dozen members of a covert ultranationalist group named Ergenekon for allegedly plotting to provoke a military coup by staging political assassinations and whipping up social turmoil. Among the plotters: two retired top generals, the leader of a paramilitary group, and Kemal Kerincsiz, a lawyer who has sued dozens of liberal intellectuals in the past for violating Turkey’s law against “insulting Turkishness.”

The Ergenekon case is only the latest salvo in a political war between the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and Turkey’s nationalist and staunchly secularist old guard. The charges, if proved, point to a brazen conspiracy to undo the liberal reforms implemented by the AKP in recent years as part of its effort to move Turkey toward entry into the European Union. The plot seems to have grown out of fears that have been growing among Turkey’s nationalists since 2004, when the nation’s accession process began, and nationalists realized that as well as offering some economic advantages, the process could require Turkey to grant concessions on Cyprus, give greater freedoms to minorities and develop a more democratic political system.

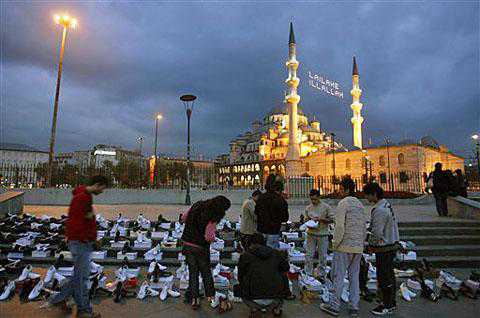

This battle is sometimes defined in the Western media as a tension between “Islamists” and “secularists,” but both terms are misleading. While AKP leaders, including Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, share an Islamist past, they abandoned that years ago and redefined themselves as “conservative democrats” who champion free markets, traditional (including religious) values and pro-EU reforms. Since it came to power in November 2002, the AKP has proved highly successful, winning a solid electoral victory in July 2007. Socially, the AKP represents Turkey’s economically minded masses, religious conservatives—including the rising “Islamic bourgeoisie” —and even most Kurds. As for those labeled secularists, they are not what one might think. Turkey’s definition of secularism is based not on the separation of mosque and state, but the dominance of the latter over the former—all mosques are simply run by the government. Secularist ideologues argue that the state also needs to safeguard society from religion. The Constitutional Court, one of the enforcers of this ideology, ruled in 1989 that “society should be kept away from thoughts and judgments that are not based on science and reason.” The result is a complete banishment of religion from the public square, including a ban on religious symbols such as headscarves.

This illiberal secularism goes back to the formative years of the Turkish republic, born from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire in 1923 under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. He and his followers were deeply influenced by the French Enlightenment, and were convinced that the influence of religion must be swept away from society. Ethnic and cultural diversity were seen as threats—hence the decision to “Turkify” the Kurds. The Kemalists’ project was in fact a cultural revolution and a government they defined as “for the people, in spite of the people.”

Though the Kemalists succeeded in building a strong state, most of the undesired social groups—such as pious Muslims and the Kurds—persisted in their demands for freedom and democracy. Yet Turkey’s establishment, represented by the military and the high courts and supported by urban elites, remains attached to Kemalism, which has turned into a rigid ideology perpetuated by an official cult of personality. The reverence shown to Ataturk, evident in his omnipresent image and oft-repeated mantras, approaches the level of leader worship you see in places like North Korea. The Ergenekon gang seems to have been an attempt by the most radical extreme secularists to preserve the old regime, which has given the old elite unchecked power and privilege. Cengiz Aktar, a liberal EU advocate, likens the plot to the coup attempted by Lt. Col. Antonio Tejero in Spain in 1981, when he stormed Parliament to halt the EU accession process and restore the Francoist regime.

Like Tejero, the alleged Ergenekon conspiracy has failed. But the ideology behind it persists. One clear sign is the shocking case launched by Turkey’s chief prosecutor, Abdurrahman Yalcinkaya, against the AKP four months ago. Defining the party “as an anti-secular threat to the regime,” he asked the Constitutional Court to close the party and ban from politics 71 of its members, including Erdogan and President Abdullah Gul, a former AKP member. Their crimes, according to Yalcinkaya, include passing a constitutional amendment to allow headscarves in universities, and comments by Erdogan such as “Turkey needs a more liberal secularism like the American one.” The notoriously illiberal Constitutional Court is expected to give its verdict on AKP’s fate sometime in August. If the AKP prevails, it will likely continue on the path to the EU. But should the court rule against the party, it will also in the process strike a major blow to Turkish democracy and the country’s EU dreams. There will no longer be any need for gangs like Ergenekon; the coup will have been realized by legal means.

Akyol is the deputy editor of the Turkish Daily News.