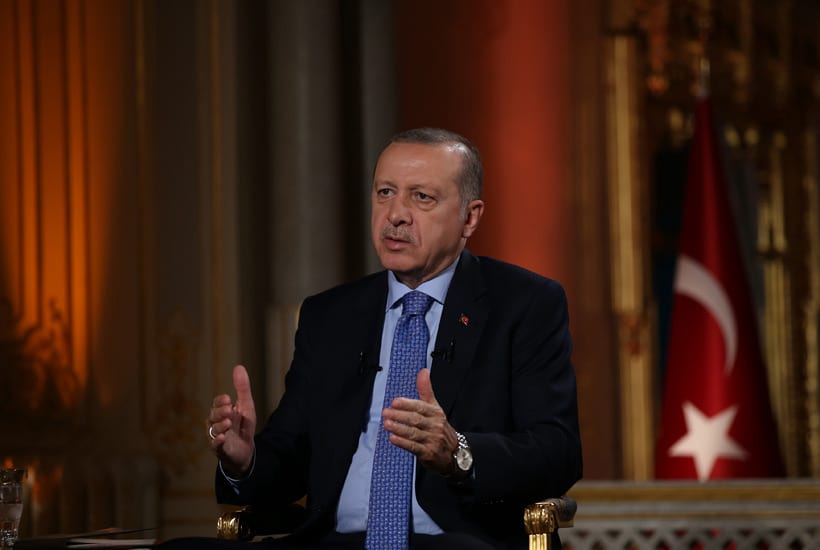

The major takeaway of this election is that Erdogan is now in possession of extremely expanded presidential powers. During his time in office, he has engineered constitutional amendments to give him one of the most powerful presidencies in modern Turkish history. And though in theory there are still some internal checks on his power, in practice little can be done to block his agenda and that of his ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP). Among other things, Erdogan now has the power to rule by decree, appoint Cabinet members, write Turkey’s budget and appoint judges — all without parliamentary approval. Moreover, the opposition cannot mobilize either the necessary 360 legislative votes needed to investigate Erdogan’s presidency or the 400 votes needed to try him in the country’s highest court.

But there are still a few checks on his power: He cannot call new elections without the support of three-fifths of parliament (or 360 legislators), and the parliament is still in charge of approving the president’s budget and his continued use of emergency powers. Now that they have an election victory under their belt, Erdogan and the AKP have hinted that they will relax the current state-of-emergency rule. Though this will please the opposition, the ruling government could easily reimpose it.

The Current Political Scene

Internally, opposition politicians and activists will remain suspicious of the AKP’s control of the media and security sectors and its ability to use them to ensure political victories. Despite a remarkably united political opposition and a strategy of trying to prompt a runoff by preventing the president from winning 50 percent of the votes, the anti-Erdogan camp was unable to gain enough momentum to unseat the president. A very high turnout (87 percent) tipped the balance in favor of AKP loyalists, and Erdogan secured a clear first-round victory with 52.38 percent of the vote according to unofficial tallies.

In parliament, Erdogan’s AKP saw its hold weaken slightly; it ended up with 295 seats — six less than the 301-seat majority it needs to govern by itself. That means that it must now rely on a coalition with its allies in the hyper-nationalist Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) to carry out its legislative agenda. The MHP performed particularly well in the election, winning 49 seats and indicating that many Turks are still very much in favor of a nationalist government. That result, in turn, means that the AKP-MHP alliance has staying power. And it also means that the MHP is in the distinct position to influence parliament.

What Next

The appeal of the MHP — as well as the emergence of a new nationalist party in parliament, the Iyi or Good Party — indicates that Turkey will only continue to strengthen its nationalist policy at home and abroad. Part of Erdogan’s continued appeal to Turks is his patriarchal and security-focused message, and the government will now be sure to ramp up its battle against Kurdish militancy (and other types of extremism) in Turkey, Syria and Iraq. Though the Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) managed to work its way into parliament — a reflection of the AKP’s weakening support among Kurds — Erdogan’s new powers and his powerful nationalist support base in parliament largely negate this victory on a practical level.

The Erdogan and AKP victories also give the ruling party the political capacity to further undermine the Gulen religious movement abroad. Once AKP allies, the Gulenists are now its rivals, and Erdogan sees their global network of influence as a potent threat to his power. He has already begun setting up rival outfits, partially through the state-run Directorate of Religious Affairs, or Diyanet, which was once a fiefdom of the Gulenists. With more opportunity to further these endeavors, Erdogan can better position Turkey as a leader of the Sunni world.

Persistent Economic Problems

Though the election put the AKP in a better political position domestically, it by no means solved every problem facing the party. After all, not even the amended constitution can fix many of the country’s larger economic challenges. Indeed, the formalization of Erdogan’s top-heavy rule will put a strain on Ankara’s relationship with external allies and partners — particularly those in Europe, Turkey’s most important export destination and source of investment. Already almost entirely in control of his country’s media and security landscape, Erdogan will be subject to even less oversight than he was before. And he has the power to make unilateral policies, even if they overstep the human rights norms that Europe values.

Still, even if it encounters some increased tension with Europe, the Turkish government will remain focused on courting further investment (using the lira whenever possible) to try to stabilize its economy. Its low currency value and high inflation rates are top economic concerns for the government to manage. And officials, such as the head of Turkey’s central bank, will have to find a way to address these issues while managing Erdogan’s disinterest in increasing interest rates.

An AKP-led government with Erdogan at the helm has become deeply familiar to Turks over the past 16 years, since the party’s first parliamentary victory in 2002. The latest win maintains the status quo, but that isn’t necessarily a good thing for Turkey’s economic situation.