Tracing the Alanian history, it is not difficult to notice that they cooperated most closely with Türks, at first with Sarmatians and Sarmatian people, Roxolans (in Türkish – Uraksy Alans, ‘Alans-farmers’), Siraks (i.e. Sary-ak people ‘white – yellow’, ancestors of Cumans), Aorses (Aor-Awar-Avars, -os is a Greek ending), Yazygs (Türks – Uzes). All historians admit the close link of Alans with these peoples, only in the definition of ethnolinguistic classification of these peoples do the opinions differ. Iranists classify them as Iranian speaking, Türkologists – as Türkic speaking, as supported by numerous historical facts.

Prior to sorting out the Alanian-Hunnish links, one should visualize Huns. The official historical science postulates that Huns, first mentioned in the Chinese sources, sometime in the II c. migrated from Central Asia to Urals, and from there in 70ties of the 4 c. poured into the Eastern Europe, thus initiating, supposably, the so-called The Great Migration of Peoples, allegedly Huns were the first Türks appearing in Europe, on the way to Europe they would have subdued Alans in the Northern Caucasus, and, led by the leader Balamber, crossed river Don, defeated Goths, Ostgoths, and Vestgoths, who infiltrated the Northern Pontic, and expelled Vestgoths to Thracia, supposedly crossing through Caucasus, they devastated Syria and Cappadocia, settled in Pannonia, and kept attacking the Eastern Roman empire. In 451 under Attila they invaded Gaul, but at Catalaun fields the Romans, Vestgoths, and Franks defeated them. After the death of Attila (453.) there were conflicts among Huns, and the German tribes devastated them in Pannonia. The Hunnish union broke up, and they left to Northern Pontic. Gradually, Huns disappeared as people, though their name still lingered for a long time as a common name for Northern Pontic nomadic pastoralists [Gumilev L.N. Huns]

Such an unreal explanation of the history by L.N.Gumilev raises questions: whether could nomads, having forded Volga, defeat strong Alans, Goths, Syrians, Anatolians (in Cappadocia), population of Pannonia, Gaul, Northern Italy? Certainly, this is unreal. How could L.N.Gumilev determine that Huns disappeared, while their ethnonym continued to last as a common name of the Pontic nomads? How he could know that ethnonym Huns for long time designated not Huns, but others? Whom? Why the advancing Romans, and together with them other peoples (more correctly, armies and colonists), did not constitute the Great Migration of Peoples, while creating a huge Roman empire, but the movement from the periphery to the central regions of the Roman empire of other peoples (liberation army, avenging colonists) is called a Great Migration of Peoples? Why Türks, at first as Huns, and then under the names of Avars, Türks, Khazars, Cumans, and Kipchaks constantly migrated from Asia to Europe? Where would they disappear there? How did they procreate so quickly in Asia? Etc. Trying to answer these questions makes it clear that the traditional presentation of Türks’ history is fashioned tendentiously, irrespectively of the real historical conditions.

Summarizing impartially all historical data based on real historical grounds, it is not difficult to suggest that Huns (Sen or Hen) at first were an undistinguished Türkic people among Türkic Scythians and Sarmatians. They started making themselves known in the 1 c. AD. The Greek historians, marking their presence in Europe, did not say a word about their arrival from Asia.

Thus, Dionysus (the end of the 1st – beginning of the 2nd c.) notes that on the Northwestern side of the Caspian sea live Scythians, Uns, Caspians, Albanians, and Kaduses… [Latyshev V.V., 1893, 186]. As we were proving more than once, Scythians were basically Türkic speaking (see ETHNIC ROOTS OF THE TATAR PEOPLE, § 3), Uns are Huns, with sound h dropped, Caspians also are Türkic ‘people of rocks’ (kas ‘rock’, pi~bi~bai ‘rich owner’), Albanians are Alans, Kaduses are Türkic Uzes~Uses among kath ‘rocks’.

Ptolemy (2 c. AD, B.3 Ch.5 – Translator’s note) writes that in the European Sarmatia ‘below Agathyrsi (i.e. Akatsirs~agach ers‘forest people’- M.Z.) live Savari (Türkic Suvars – M.Z.), between Basternae and Rhoxolani(Uraksy Alans, i.e. ‘Alans-farmers’ – M.Z.) live Huns [Latyshev V.V., 1883, 231-232].

Philostogory, living in the end of the 4 c. (i.e., when, in the opinion of certain scientists, Huns moved to Eastern Europe), describing Huns, does not say a single word of their arrival from the Asia, and writes: ‘These Uns are probably the people who the ancients named Nevrs, they lived at Ripean mountains (Don Ridge S. of Donets river, Mid-Europian Uplands N. of it – Translator’s note), from which come the waters of Tanaid’ [Latyshev V.V., 1893, 741].

Zosim (2nd half of the 5c.) suggests that Huns are Royal Scythians [Ibis, 800]. The impartial analysis of the ethnographic data provides a basis to state that Royal Scythians were ancestors of Türkic peoples [Karalkin P.I., 1978, 39-40].

Thus, among the peoples named Scythians and Sarmatians, at the beginning of our era, the Huns make themselves known, in the Assirian and other Eastern sources they were mentioned among the people living in the 3rd millennium BC. In the 4-th c. in a fight for a domination in the Northern Caucasus they defeated the Alanian power, and together with them revolted against the colonial policy of the Roman empire, at first in Cappadocia, then in the western part of the empire, where appeared new Gothic colonizers. Naturally, neither the Huns, nor the Alans, did not move to the West as a people, as it is imagined by the supporters of the ‘Great Migration Of Peoples’, it was the Hunnish-Alanian army that penetrated deep into the West. The main body of the Hunnish and Alanian peoples remained in the same old places of habitation.

In the end of the 4 c. the Huns, together with the Alans, fell on the Goths, who wanted to colonize the Northern Pontic. The main historian of the Huns and Alans of this period, Ammianus Marcellinus, frequently equated them, for they were ethnically very close. ‘Ammianus Marcellinus not only emphasized that precisely the assistance of Alans helped Huns, but also quite often called attackers Alans’ [Vinogradov V.B., 1974, 113].

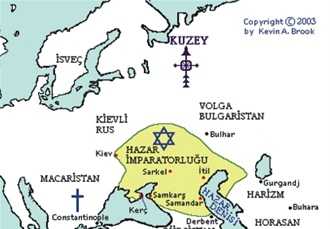

After the death of Attila (453), the Hunnish union gradually disintegrated, and Huns as a ruling power do not appear any more, they fused with the Türkic Alans and Khazars, while keeping their ethnonym Hun (Sen).

In the Gaul the Alans entered into a close contact withthe Vandals (Eastern Germans), together they devastatedthe Gaul, and in the 409 they settled in Spain, wherethe Alans received the middle part ofthe Lusitania (later – Portugal) and Cartagena. However, in the 416the Vestgoths entered Spain and defeatedthe Alans. Inthe May of the 429 the Vandal King Geizerix together withthe subordinated Alans went to Africa, and, defeating the Roman armies, created a new Vandal and Alan state. As the result the Alanian troops dissolved amongthe Vandals andthe local population. But in the Northern Pontic and in the Caucasus the Huns and Alans continued to cooperate closely.

Following the disintegration of the Hunnish empire, in the decentralized period, various tribes and peoples tried to become the ruling group, therefore in the Byzantian sources frequently appear ethnonyms: Akathirs, Barsils, Saragurs, Savirs, Avars, Utigurs, Kutigurs, Bolgars, Khazars. All these ethnonyms belong to the Türkic populations. The Barsils are the inhabitants of the Berselia (Berzilia), which in many sources is considered as the country of the Alans. Here is an obvious identification of Alans with Barsils~Bersuls, deemed related to Khazars [Chichurov I.S., 1980, 117]. More than that, the Khazars also came from Berzilia. So, Theophan in 679-680 writes: ‘From the depths of Berzilia, the first Sarmatia, came the great people Khazars and began to dominate all the land on that side down to the Pontic Sea’ [Chichurov I.S., 1980, 61].

From the 5 c. among the Caucasian Alans, i.e. numerous Türkic peoples, also began to make themselves knowntheother tribes: Khazars, Bulgars, Kipchaks etc. After the brilliant performance of the Türkic peoples, led by the Huns, against the colonial policy ofthe Goths andthe Romans, the Huns ceased to be ruling, andtheAlans and Khazars took their place, competing on the political arena up to the 10-th c. ‘From the 5-th c. the push of the Khazar Khaganate grows, establishing control overthe Alans’ [Vinogradov V.B., 1974, 118]. In the 8 c., at the time of the Alanian expansion, the Alans once again proved that they supported Khazars. ‘The 10-th c. marks a turn. Now the Khazars had to recognize their former vassals with the following words: ‘The Alanian Kingdom is stronger and tougher than all other peoples around us’ [Vinogradov V.B., 1974, 118-119].

In the 11-th c. others nations begin to raise in the Northern Caucasus, Kipchaks (Russ. Polovets), who at once joined with the Alans, and established peaceful and loving relations [Djanashvili M., 1897, 36]. In this area the Alans, together with the Kipchaks, adopted Christianity.

In the 1222 Alans and Kipchaks come out together against the Mongolo-Tatars. Seeing that they together represent an undefeatable force, the Mongolo-Tatars used a trick. ‘Seeing a danger, the leader of the Chengizkanids (Subetai – Translator’s note)… sent gifts to the Kipchaks and ordered to tell them, that they, being the same kin as the Mongols, should not rise against their brothers and be friends with Alans, who are entirely of another lineage’ [Karamzin N.M., 1988, 142]. Here the Mongolo-Tatars figured, apparently, that their army at that time consisted primarily of the Kipchak Türks of the Central Asia, therefore they addressed Kipchaks as kins, andthe Alans ofthe Caucasus were partially Kipchaks (ancestors of Karachai-Balkars), and partially Oguzes (ancestors of Azerbaijanis -the inhabitants ofthe Caucasian Albania, Alania).

It is known that soon all Kipchak steppes passed into the hands of Mongolo-Tatars. The Volga Bulgaria, the main component of whose population was referred to as the Yases, subordinated to the Mongolo-Tatars in 1236, and the Alans – Yases of the Northern Caucasus in 1238.

Thus, Alans made their celebrated military and political route hand-to-hand with their Türkic kins: Huns, Khazars and Kipchaks. From the 13 c. Alans-Yases cease to be ruling among the other Türkic people. But it does not mean at all that they physically disappeared, they lived among others Türkic people and gradually entered into their ethnicity, accepting their ethnonym. Such a strong, scattered along all Eurasia people as Alans-Yases, cannot be equated to Iranian speaking Ossetians by a single trait, and could not be suddenly reduced ‘by a miracle’ to the strictures of the Caucasus Ossetians.

If the Scythians, Sarmatians and Alans were Ossetian speaking, all Eurasia should have Ossetian toponyms. They do not exist, unless artificially (quasi-scientifically) produced. Thus, in all their attributes the Alans were Türkic, and took part in the formation of the many Türkic peoples.

Zakiev M. Z.

PROBLEMS of the HISTORY and LANGUAGE

Collection of articles on problems of lingohistory, revival and development of the Tatar nation

Kazan, 1995