- Maps

- Vilayet of Sivas

- Sandjak of Sivas

Colorized Photographs from Sivas/Sepasdia

Bringing Color into the Lives of the Ottoman Armenians

Author: Azad Balabanian, 18/08/20 (Last modified: 18/08/20)

Introduction

As we progress into the 21st century, the tools at our disposal to document, describe, and relive our history progress alongside us. The tools help us shape the narrative about ourselves that we live by, that we tell our children, and pass on to generations.

The 20th century brought forward a new form of artistry, Photography, adopted and mastered by Armenian craftsmen in the Ottoman Empire like Abdullah Brothers, Yessai Garabedian, and Zorapapel Krikor Donatossian. Their work left us with mementos of the lives of the Ottoman Armenians, be it their family photographs, weddings, graduating scholars, or purely, still life.

For the next century, Photography continued to develop and become more widespread. It transitioned from a chemical process into a digital one, taking advantage of the advancements in software and silicon. Not only did the cameras change, but the medium in which photographs were viewed did as well. Instead of images having to be printed and varnished, today a photograph can now be shared to billions of people with smartphones instantly.

Just in the last decade, another large leap in imaging and computer science has been driven by something called Machine Learning, commonly referred to as Artificial Intelligence. As a result of the endless amount of data generated and shared on the Internet, computer scientists can create and “train” machine learning models to be able to “understand” the underlying principles between certain data to extrapolate and generate information in places where there are none.

One area of interest is the ability to colorize black-and-white photographs, which is a profound use of machine learning technology. Given the depth, variety, and extent of the Houshamadyan archives, we decided to give the best colorizing machine learning model, DeOldify, a try to determine how well a generalized model can work on any photograph.

It should be noted however, that attempting to colorize a black-and-white photograph, the intent is not to “improve” or “change” the original image but to offer a new perspective into the world that it captures.

Typically, Photography archives focus on preserving and presenting the original data in its most original and authentic state. It should be noted that the purpose of the Houshamadyan Archives is to “reconstruct” Ottoman Armenian town and village life, rather than simply putting forward the raw photographs, objects, and materials. Colorizing photographs certainly falls within that definition.

The images of this article are entirely colorized using the open-sourced DeOldify machine learning model.

1) Sivas, the Kltian family. Hagop Kltian is seated, to his left is his wife Takouhi Kltian. The others are their daughters – Baydzar, Shnorhig and Dirouhi (Source: Arousyag Mgrdichian collection, Istanbul).

2) Sivas, the Kltian family. Hagop Kltian is seated on the right. Hagop’s wife, Takouhi, is standing in the middle. The others are Hagop’s daughters, Baydzar and Lousig. After his first wife’s (Dirouhi) death, Hagop remarried with Takouhi, who was a widower and had a son named Missak (Source: Arousyag Mgrdichian collection, Istanbul).

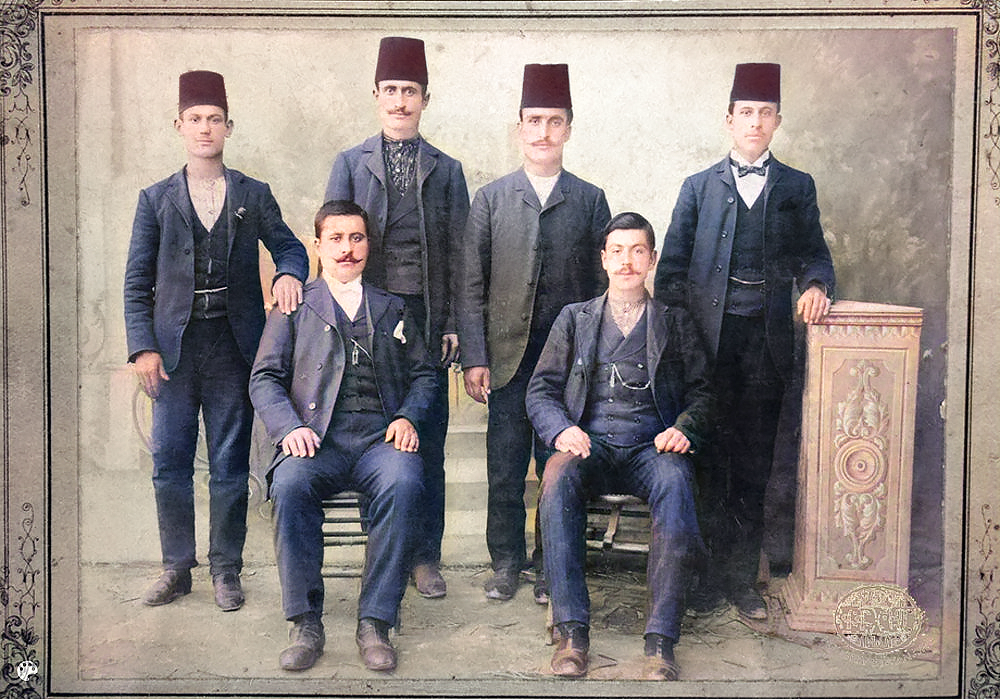

3) The wedding photograph of Avedis Ghazarian and Parantsem Ghazarian (née Shahinian) taken on 12/23 October 1909, in Sivas by the Enkababian Bros. (Source: Avo Gazal collection, New York).

4) The Didizian family from Gürün (located in Sivas province), ca. 1910. Standing (from left): Mania Didizian, Dikranuhie Didizian (née Nahabedian), Setrag Didizian, Hagop Haig Didizian. Seated: Haigag Hagop Didizian. Photograph by Encababian Bros. (Sivas/Sepasdia) (Source: Didizian family collection, London).

5) An Armenian family of the city of Sivas/Sepasdia (Source: Nubarian Library collection, Paris).

6) Haroutyoun Efendi Kasabashian, photographed on his horse in Sivas/Sepasdia (Source: Kasabach/Getoor collection, Southfield, MI).

The Technical Details of How DeOldify Works

DeOldify is a “deep learning” model that has been “trained” on millions of photographs to be able to predict the colors of a color-less photograph.

How does it work? We shall attempt to explain the underlying technical principles of DeOldify as well as discuss our results in an attempt to demonstrate the limitations of machine learning and understand the areas that we hope to see improved in the near future.

Training Phase

A deep learning model works by first being trained with data that includes both the questions and the correctanswers, so that the model can learn and infer the steps going from a “question” to its correct answer.

In fact, this is very similar to we as humans learn: when studying a subject like math or science, it’s useful to have both the question and its answer, so that you can work out the steps to reach the desired answer (otherwise, you’d be running blind).

DeOldify combines advancements in machine learning, namely Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), where the model is first trained on a set of data with both the question and its answer, and with that knowledge, tries to answer questions that it hasn’t encountered before.

In the training phase, the model needs a lot of data to first learn the underlying principles that we want it to understand, which in this case is the difference between a colored photograph and its black-and-white counterpart.

The model consists of two main components: the Image Generator and the Image Critic. In the following steps, you will see how these two components interact to create the deep learning model.

First, the Image Generator needs to learn how to colorize an image.

- The software downloads images with color from the ImageNet database (which is an open-sourced database with millions of images scientists use to train various machine learning models with).

- The images’ colors are removed so that they are now black-and-white.

- The Image Generator attempts to re-color those images, with a random set of colors.

- It then compares its attempted colorizations with the images’ original colors to determine how close its prediction was.

- Given its last attempt, the Image Generator tries to color the image again and again, until it reaches a result that is good enough.

At this stage, the model’s second component is introduced: the Image Critic, which is trained to be able to detect whether an image is real or fake, as in, whether the colors of the image it is critiquing is its true colors or colorized by the Image Generator.

To be able to achieve accurate image colorization, the colorization result needs to be good enough to trick the Critic into thinking that the image’s colors are not colorized, but are in fact, real.

If the Critic is not very good at detecting colorizations, the results that pass its test will not look very realistic. For that reason, the Critic itself needs to be trained to be able to have a very high standard of what image can pass its test.

The Image Critic is trained with the following steps.

- The Image Generator colorizes a number of images.

- The Image Critic is given a set of images, some that are colorized by the Generator (fake), and some that are colored images from ImageNet (real).

- It attempts to critique whether each image’s colorization is real or fake. It is then given a score on whether its critiques were accurate or not.

- Given the results of its previous critiques, it tries again and again until its critiques are accurate.

Now that both the Image Generator and Image Critic are trained to be good at generating colorized images and being able to detect whether the colorizations are real or generated, the final stage of training is reached.

The Image Generator and the Image Critic have to train against one another, with one trying to out-learn and out-perform the other and be able to generate the best colored result. They iteratively go back-and-forth, generating new colorizations, critiquing them, and trying to pass the real-or-fake test.

This is why this method is called a Generative Adversarial Network, as the Generator and Critic are adversaries, working against each other and trying to fool one another.

The images in the article are the results that have come out of the DeOldify model, meaning that their colors were generated by the Image Generator, critiqued by the Image Critic, and passed its real-or-fake test.

Looking Forward

The results we show in this article are some of the best results we’ve been able to achieve.

As you can most likely see, however, the colorization attempts are not 100% accurate. There are patches where the image is still grey, or colors in the image aren’t particularly accurate.

Determining why certain results are better than others is not particularly an easy thing to do with machine learning models, as the underlying principles that the model learns during training are abstract and partially inaccessible to the scientists that create them.

Of course, the quality of the original black-and-white photograph makes a large difference in the colorization results. We’ve found that photographs with high contrast produce better results than photographs that are “washed-out”.

Other reasons for inaccuracies could be based on the images that the model was trained from, biasing the model towards the things, people, and places in the images found in the training data.

The potential, however, to use ever-improving software to bring our people and history clearer is very exciting.

As the Houshamadyan motto is to “reconstruct the life of the Armenians in the Ottomon Empire”, this colorization attempt is a literal way to bring our history from the Ottoman times into full color.

Try DeOldify With Your Own Photos!

The benefit of the Internet and open-source software is its accessibility to anyone!

If you’d like to colorize your own black-and-white photographs, the website MyHeritage has built the latest version of DeOldify into its website, allowing you to colorize up to 10 photographs for free (it will require you to create a free MyHeritage account).

For people that are more technically savvy and are using a modern computer, you can access the open-source version of DeOldify on GitHub to colorize as many photographs as you’d like. You can use its “stable” version to get more consistent colors or its “artistic” version to get more colorful results. They even have a version for colorizing video!

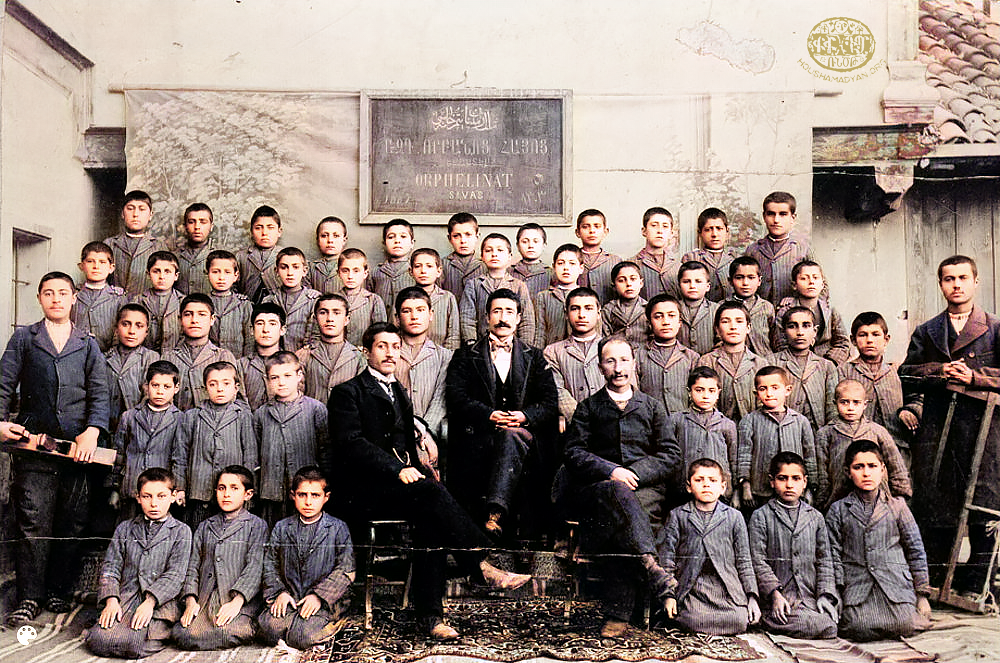

1) The graduates of the Armenian school in Sivas/Sepasdia, around 1912 – Hrant Shahabian should be in this photo (Source: Kasabach/Getoor collection, Southfield, MI).

2) A unique photo. From the presence of musical instruments, books, and newspapers we can assume that the photographer and the men in the photograph had the desire to produce an artistic photograph impregnated by their intellectual life. The location is unknown, but we assume that the photo was taken either in Sivas/Sepasdia or in Marsovan/Merzifon sometime after 1908. Mihran Toumajan is sitting second from the right, he’s in a white shirt and holds what appears to be a newspaper on his lap. Right next to the feet of the young man sitting in the center we can see the ARF Dashnaktsutyun’s “Droshak” «Դրօշակ» official newspaper, with the image of the revolutianary Sevkaretsi Sako, on the cover (Source: Turnamian collection, USA).

About the Author

Azad Balabanian is a Cinematographer and Photogrammetry Artist specializing in 3D scanning and Virtual Reality.

His work has been featured by DJI, Oculus Medium, and the Institute for the Future, as a creative technologist pushing the medium in a new direction.

His work is largely based around a 3D mapping technique called Photogrammetry, which produces photorealistic 3D reconstruction of places from around the world. His love for Aerial Cinematography has taken him from Iceland to Armenia, creating cinematic short films, and documenting a vast amount of history.

He is the Dir. of Photogrammetry at Realities.io and is the host of the Research VR Podcast, hosting discussions about the Science and Design of Virtual Reality and Spatial Computing.

houshamadyan