Members of the Turkish police counterattack team responsible for guarding President Recep Tayyip Erdogan stand in front of a mosque as Erdogan departs, following Friday prayers in Istanbul, May 29, 2015. (photo by REUTERS/Murad Sezer)

Estranged from his family and ravaged by a drug habit for most of his adult life, Murat reckoned he had nothing to lose the day he left his home in Ankara for the self-proclaimed caliphate of the Islamic State (IS). As he crossed the Syrian border in full view of Turkish troops in February 2014, Murat concluded that his own government was equally nonchalant about his future. When the 29-year-old returned home late last month, he discovered that the rules of engagement along Turkey’s border had changed. Apprehended by the Turkish military within minutes of his crossing, Murat was arrested and charged with membership in a terrorist organization.

Turkey has recently moved to counter Islamic State recruitment in the country, but it faces a difficult time reintegrating jihadist returnees from Syria and Iraq, some of whom have been traumatized by their experiences.

Author Noah Blaser Posted July 13, 2015

Released pending trial, Murat returned to his tumbledown home district of Haci Bayram, in Ankara, to find police staking out the men who had helped funnel recruits like himself into Syria. “It was never like this before,” said Murat, who asked that his real name be withheld for fear of retribution. “Now there are police here. Now we are being followed.”

On July 10, Turkey launched its first major crackdown on IS’ domestic recruitment network, detaining 18 Turkish citizens and three foreign nationals and confiscating a cache of assault weapons and military uniforms. Of the 21 people taken into custody in raids around the country, including in Haci Bayram, police detained at least 12 of the suspects and pressed charges against the other nine.

While Turkey has markedly stepped up detention of would-be foreign jihadists at airports and border crossings over the past year, it had avoided domestic crackdowns and neglected censoring Turkish-language jihadist websites and other media.

“After launching 10 raids this past week, Ankara is showing it thinks the IS can no longer be managed by de facto nonaggression,” said Aaron Stein of the Royal United Services Institute, a London think tank. “Turkey is conceding to a more US-styled approach,” he said, pointing to a meeting between US and Turkish officials just days before the arrests. Turkish officials, however, have downplayed the significance of the meeting. “Serious operations take months to plan out and Turkey has long showed its resolve against the [IS],” said a Turkish official who requested anonymity.

In Haci Bayram, the arrests represent a once unimaginable about-face. Last year, despite reports that the neighborhood — long blighted by drug use and sweeping urban renewal — had become a major IS recruitment hub, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan denounced foreign news reports of jihadist recruitment in Haci Bayram as a campaign of “shamelessness, sordidness and vileness.” Turkey’s pro-government press forcefully denied the reports and took aim at New York Times reporter Ceylan Yeginsu, who fled the country amid a flurry of death threats.

Although Turkish police have acted in Haci Bayram and other IS hot spots, it will be a struggle to manage the returning fighters who in the end walk free. The Turkish official estimates that around 1,400 Turkish nationals have joined IS, the al-Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra and other rebel groups in Syria since 2012.

Many returnees will earn acquittal barring explicit evidence of violent acts committed in Syria, said Omer Behram Ozdemir, a researcher at Sakarya University who focuses on jihadist extremism in Turkey. “Unlike the Turkish jihadists who fought in the Bosnian, Afghan and Chechen conflicts, those who fight with [IS] see their conflict extending beyond the borders of Syria,” he warned.

Near his new apartment on the streets of impoverished Haci Bayram, Murat says he is slowly reconnecting with his family and does not see Turkey as enemy territory. That conviction is tied to his belief that Turkey won’t decisively crack down on IS while the jihadists battle Kurdish militants in northern Syria.

When asked about the recent arrests, his view of Turkey quickly soured. “We will regard any punishment in [Turkey] as a reward,” Murat declared. Emotionally volatile and wracked by post-traumatic stress disorder, Murat vacillates between disbelief at the violence of his actions in Syria and longing to return to combat. He expressed bewilderment at his commander’s order to carry out a grisly execution of a peshmerga captive in Iraq earlier in the year. “I couldn’t sleep for 10 days,” he said. Staring ahead blankly, Murat added unapologetically, “The laws are strict, but these are our commandments.”

Ankara has admitted to the security risk the former jihadist fighters pose, but Turkish officials have declined to comment on how they plan to rehabilitate them. “So far, I haven’t heard of any plans for dealing with returnees from [IS],” said Ozdemir. Turkish Interior Minister Sebahattin Ozturk conceded July 7 that “negligence” had allowed Orhan Gonder, a 20-year-old returnee from IS, to elude Turkish intelligence and carry out twin bombings at a June 5 election rally in Diyarbakir. Four people were killed in the attack.

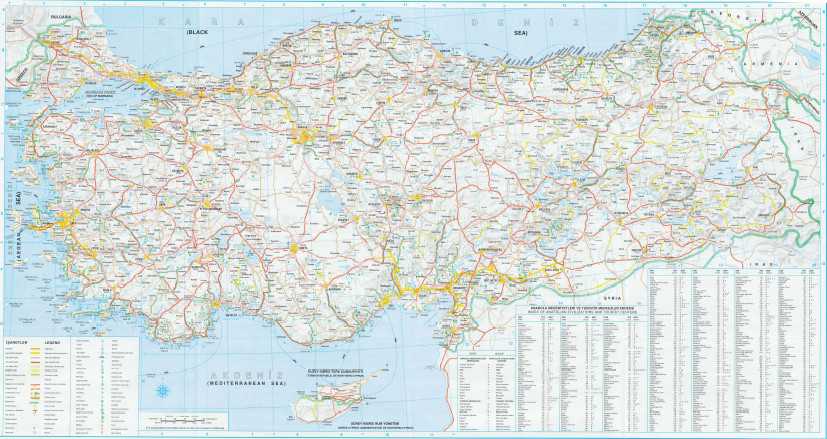

If Turkey sustains its crackdown on native-born jihadists, it will find more of them within its borders than ever, Murat warned. Wary of a 10-year prison term if he skips trial, he has no plans to return to Syria. He also said IS recruits feel trapped in Turkey by the buildup of troops between the border towns of Kilis and Karkamis that has squeezed IS’ last smuggling route into Turkey after it lost the border city of Tell Abyad to Kurdish forces in June.

“The war is also getting harder in Syria,” he said. Claiming to have been detained by fellow militants wary of escapees in Syria, he added, “More and more, fighters want to come home.”

It remains to be seen how serious Ankara’s crackdown will be. The New York Times reported July 10 that some suspects had been freed just hours after their detention. Although the crackdown has included key names, including IS proponent Murat Gezenler, the jihadist web editor Abdulkadir Polat and pro-al Qaeda pundit Cumali Kurt, Ankara notoriously released the foremost pro-IS preacher, Abu Hanzala, during the height of the riots last October over Ankara’s response to the siege of Kobani.

How Ankara deals with those it cannot hold in jail cells is a no less critical issue, said Ozdemir. “[IS] will publish its Turkish propaganda magazine’s new issue soon. We will see if it mentions Turkey’s policy on Turkish pro-IS supporters,” he said. “Regardless, returning [IS] fighters will pose a serious threat to the Turkish state.”

Dogu Eroglu contributed to this article.

EVEN IF HE MADE A ROCKET THAT WOULD REACH THE MOON HE NEVER TOOK IN THE FACT THERE IS NO OXYGEN IN SPACE OR ON THE MOON

de man wordt steeds zieliger…

misschien denkt hij dat minaretten de raketten zijn…of zo

Je vindt dit soort gedrag ook bij lijders aan syphillis, gevorderd stadium

Tijd voor het gesticht voordat er echt domme dingen gebeuren

I may be the only one to notice this, but the author refers to the show “Mythbusters” and says

“the final design did not attempt to utilize materials of the period;”

I would like to clarify that the reason the final design did not utilize materials of the time is because they try to test the myth using time appropriate materials and methods, and if this fails, they then attempt to re-create it using modern methods.

Did he bring back drawings as proof?

He was unable to to do that because, as you probably know, drawings are forbidden by the Koran.

@Roy Martin, Mehmet II was the first emperor who painted his portrait.

@Kutay. Yeah after him, his son sold the portrait to non-muslims and banned to drawing

This guy is the president of a nation. How scary is that?

Actually, it was pretty scary having George W Bush in the hot seat. He and Mr Erdoğan would have some verrry interesting conversations – without needing to get stoned first.

Unfortunately, he is our president

The scary thing is if you living in that nation and witness all the things that man do and see how much supporters he has.This is an embarasment.

Poor secular turkish people this tayyip is the emberesment of Turkey