The Structure of Intra-State Conflicts in the Post Cold War Era

Prof. Dr. Muzaffer Ercan YILMAZ Bursa Uludağ University

This work aims to provide an analytical discussion on the dynamics of intra-state conflicts that seem to have replaced the ideological clashes of the Cold War as the principle sources of current conflicts. As for methodology, the study relies on a large- n case study. By looking through major ethnopolitical conflicts around the globe and trying to find out some main points in common, the study reaches the conclusion that such conflicts are correlated with, but not limited to, the desire to express cultural identity, discrimination, anti-democratic political system, economic underdevelopment and unjust distribution of national wealth, unresolved past traumas, as well as external support. The study also reveals that ethnopolitical conflicts cannot be resolved through force only. Although a certain degree of the use of force would be functional in terms of controlling radical groups and thus would be an integral part of the overall conflict resolution process in intra-state conflicts, it would be quite erroneous to assume that such conflicts can be resolved through force only. The disadvantaged groups whose subordinate status is maintained through force and repression often nurture deep grievances against privileged groups, even if they may be hesitant to act on them in the short run. Yet in the long run, when conditions become suitable, they take action to change the status quo for the better. Hence, in the resolution process, multi-level efforts are stressed to be needed by domestic and international actors to be responsive to the underlying causes of intra-state conflicts.

Key words: Intra-State Conflicts, Internal Conflicts, Post-Cold War Era, Intra-State Conflict Analysis, Intra-State Conflict Resolution

⦁ INTRODUCTION

Until the end of the Cold War, the conventional wisdom in the world was that ethnicity and nationalism were outdated concepts and largely resolved problems. On both sides of the Cold War, the trend seemed to indicate that the world was moving toward internationalism rather than nationalism. As a result of the threat of nuclear warfare, great emphasis on democracy and human rights, economic interdependence, and gradual acceptance of universal ideologies, it became fashionable to speak of the demise of ethnic and nationalist movements.

Despite contrary expectations, however, a fresh cycle of ethnopolitical movements have re-emerged in Eastern Europe (including the Balkans), Central Asia, Africa, and many other parts of the world. In fact, with the end of the Cold War, which clearly increased international cooperation, while decreasing the possibilities of inter-state wars, the main threat to peace does not come from major inter-state confrontations any more, but from another source: intra-state conflicts, conflicts that occur within the borders of states. These conflicts have replaced the Cold War’s ideological clashes as the principal sources of current conflicts. To be sure, from May 1988, when the Cold War was coming to its end, to the present day, there have been 58 conflicts the United Nations (UN) intervened and only 3 of them were inter-state in character (Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990, Chad-Libya border dispute in 1994, and Ethiopia-Eritrea border dispute in 1998-2000). If we add the Iraqi invasion by the United States to the number 3, the total number of inter-state conflicts during the whole post-Cold War period is only 4, whereas 54 overt internal conflicts have occurred in the same period.1

The era of intra-state conflicts appears to be holding. However, the international community cannot be said to be well prepared to this trend. Major international organizations, including the UN, were designed to cope with inter-state problems, historically the main source of threat to global peace and security. On the other hand, the fact that internal conflicts occur within the borders of states made major international actors reluctant to intervene as well, either for legal concerns or for concern to avoid probable loses.2 Thus, unless they really escalate, the international community has preferred not to involve in intra-state conflicts.

Yet such conflicts would be as serious, costly, and intense as any in the past. And somehow they need to be managed and resolved, or else international peace and security will not be in a stable situation, for even if intra-state conflicts appear to be

1 Source: UN statistics, September 12, 2019, obtained from the official UN web site, www.un.org

2 For example, during Clinton administration, the US government issued PDD-25 (Presidential Decision Directive-25), limiting the conditions that the US can participate in UN peacekeeping operations. For details, see The Clinton Administration’s Policy on Reforming Multilateral Peace Operations, Washington, DC: US Department of US Publication 10161, May 1994.

local, they can quickly gain an international dimension due to global interdependence and to various international support. In fact, when external parties provide political, economic, or military assistance, or asylum and bases for actors involved in local struggles, these conflicts inevitably assume an international dimension. Undoubtedly, effective management of intra-state conflicts by domestic and international authorities presupposes an understanding of their nature and causes. This study attempts to provide some explanations about the causes of such conflicts by observing many points that seem to be common in major internal conflicts around the globe.

⦁ INTRA-STATE CONFLICTS AND ETHNIC IDENTITY: AN OVERVIEW

Before getting into a detailed discussion, a few points need to be clarified regarding the scope of intra-state conflicts and the relevance of ethnic identity in them.

The essence of intra-state conflicts involves inter-group rivalries between two or more ethno-cultural groups that feel different from each other. But this rivalry would especially be translated into an overt conflict when the groups (or at least one of them) view their relationship as unfair under the existing political order. The groups that perceive themselves as underprivileged, then, would seek changes through conflict, ranging from recognition of cultural rights to autonomy, to political separation or full independence. The conflict is usually directed towards the members of dominant group(s) or to the state authority dominated by them. Thus, in almost all intra-state conflicts, the very legitimacy of the state is also under question and domestic law is considered breakable as it is perceived to be in favor of dominant groups.

The ethnic criteria used by conflicting groups to define themselves may include common descent, shared historic experiences, or valued cultural traits. In some cases, race and blood ties may also be very important, but in general, there is no warrant for assuming that any one basis for ethnic identity is inherently more important than any other. In the final analysis, the self-attachment to a group is a matter of personal feeling, which may be subjectively defined based on different criteria.

It should be also noted that as we learn from research on human development, no one is born with a distinct identity. One’s sense of self, or identity, is slowly developed as the individual enters into a wide variety of social interactions with other individuals in a given environment. Thus, in this process of socialization, the factors impacting on the crystallization of ethnic identity may vary. While some social environments give more weight to race or common descent, some others may emphasize other bases for ethnic identity, such as religion, language, or shared culture.

But what we know for sure is that, ones ethnic identity is formed, it becomes rather resistant to change. Although change and mutability are endemic in all social identities, hypothetically speaking, we observe that this happens only exceptionally. The reason for this lies in the fact that there usually is a very strong relationship

between ethnic identity and one’s sense of self. Since an established ethnic identity satisfies the individual’s need to know who s/he is and who others are, as well as the need to belong, to love and to be loved, it is rather inflexible to change. Indeed, the self-esteem of individuals often rises and falls with the fate of their group. A success of an in-group uplifts the individuals in that group and a failure hurts them. The fact that people may be willing to die rather than to change their identities and that the group may cling to its identity all the more when political and military pressure is intensified are perhaps understandable within this context.

While ethnic identity is a natural and universal phenomenon, it would be erroneous to assume that ethnic identity itself is a direct cause of ethnic conflicts. If that were the case, then so many ethnic groups around the globe would be in constant conflict just on the ground of their differences. But we observe that this is not the case and indeed, cooperation among diverse ethnic groups is as common as inter-group conflict, if not more common. In light of that, it would be reasonable to assume that intra-state conflicts result from certain negative conditions and our duty now is to discuss some of such conditions by looking through many common points in different conflicts.

⦁ CONDITIONS ENCOURAGING OR LEADING TO INTRA-STATE CONFLICTS

The Desire to Express Ethnic Identity

First of all, whether we look at the intra-state conflicts that the UN has intervened in the post-Cold War period or major others, it becomes apparent that these conflicts are not independent of the desire to express distinct group identity. Such conflicts tend to occur when groups feel serious restrictions on the expression of their ethno-cultural distinction. The restrictions talked about here may involve limitations to the use of local language (i.e., in schools and courts), exclusion of certain ethnic groups from political power, or limitations to the expression of local customs. In general, the greater the scope of real or perceived restrictions the more likely the potential for ethnic challenge against the status quo.

Hence, contrary to the common sense, ethnic identity is valued in and of itself, and for many ethnic groups, the mere urge to express their distinct identity may be independent of the pursuit of economic well-being or power. As Ted R. Gurr astutely observed:

“…One cannot explain away the significance of ethnic identity by arguing that what really motivates ethno-political groups is the quest for well-being. The important factor is that such groups organize around their shared identity and seek gains for members of their group. It is seriously misleading to interpret the Zapatistas as just a peasants’ movement or the Bosnian Serbs as the equivalent of a political party. They

draw their strengths from ethnic and cultural bonds, not associational ones…” (Gurr, 1996: 53).

A strong sense of group identity and collective grievances with respect to real or perceived restrictions are both necessary conditions for sustained ethnic mobilization, but they are not sufficient. Some degree of cohesion is also needed to convert common grievances and identity into purposeful action. A group’s cohesion is shaped by its social, political, and economic organization, past and present. Cohesion tends to be greater among groups held together by dense networks of communication and interaction. It is also greater among groups concentrated in a single region, such as the Tamils of Sri Lanka, rather than dispersed, like the Chinese of Malaysia.

That aside, an effective leadership is usually necessary to form coalitions and policies toward ethnic mobilization. Leadership helps expression of shared grievances of groups and translates them into group action. Failure to create a strong leadership and thus to form coalitions particularly reduces the scope and political impact of collective action, making easier for states to co-opt or ignore ethnopolitical challengers.

Discrimination

Another common point in different intra-state conflicts around the globe seems to be discrimination. The most apparent aspect of discrimination involves unequal treatment of minority groups by dominant groups and not creating conditions for their progress. In most Third World countries, inequalities among ethnic groups in status and access to political power have also been deliberately maintained through local law and public policy. State building almost everywhere in the Third World resulted in policies aimed at assimilating minority peoples, restraining their historic autonomy, and extracting their resources and labor force for the use of the state, dominated by a certain ethnic group, or groups. Some minority peoples, including most of the overseas Chinese of Southeast Asia have been able to share power and prosperity at the center of new states. Some others, particularly those in Africa where the reach of state power is limited, have been able to hold on to de facto local autonomy. But the general effect of state building or expansion of state power in most parts of the world has been to substantially increase the grievances of most ethnically distinct groups, those who have either not being strong enough to protect their local autonomy or not been allowed to participate in power at the center.

Having said that it should also be mentioned that discrimination is not limited with legal discrimination, most evident in the Third World. Evident inequalities in status and well being may also cause deep grievances for underprivileged ethnic groups elsewhere. For instance, minorities in Western countries usually work in lower-status jobs and have a clearly low level of income. Even though there is no legal restriction for upward social mobility, these people are mostly entrapped in underprivileged conditions and very few can actually get ahead in the system. The discontent regarding

their disadvantage in comparison with privileged groups may, at times, motive these people for political mobilization. Many minority groups’ uprisings in France a year ago, the hidden tension between White and non-White Americans, between the Black and White in South Africa do not seem to be independent of this kind of structural discrimination. The perception of limited possibilities for upward social mobility tends to anger and motivate many minority groups to utilize conflict as a means to achieve what the privileged groups have.

Finally, minorities in multi ethnic states often face cultural discrimination too. That is, social practices would be such that while dominant group culture is valued, minority norms and customs are disvalued and marginalized. Some examples of cultural discrimination may include making fun of minority languages and customs, portraying minorities as “bad men” in movies and television programs, excluding them from popular social gatherings, and negatively stereotyping them as a group, in general.

By discrimination policies, dominant groups aim to assimilate minorities, but indeed, in-group solidarity usually increases within ethnic groups facing serious legal, structural or cultural discrimination. The groups whose underprivileged status is maintained through repression may be hesitant to act on dominant groups in the short run, but they certainly nurture deep grievances against them. Eventually, these grievances may manifest themselves in conflict when conditions become “ripe”3 for ethnic mobilization.

Political System

Just having talked about the issues of the urge to express ethnic identity and discrimination, the feature of political system should also be discussed in this regard as these issues are also linked with it. It is usually the case that liberal democracies provide many structural mechanisms preventing, at least, legal discrimination and easing identity expression. For example, in most liberal democracies, minority rights are strictly protected by law, different ethnic groups have a space to exercise their group identities, and social problems can find democratic channels to express themselves. Equally or more important, the distribution of political power can be shaped, or re-shaped, through political elections. Therefore, issues concerning ethnic groups can be peacefully dealt with in liberal democracies before they escalate to large-scale conflicts.

That aside, a burgeoning literature has discussed the pacific culture of democracies, usually called as “democratic culture”. In its origin, democratic culture is driven from the interactions of individuals with the system of democracy but in time, it becomes a

3 By ripe, it is meant those conditions making ethnic mobilization possible, such as enough in-group power to combat with dominant groups, cohesion, leadership, organization, external support, and so on.

reality dominating inter-individual relations. Democratic culture promotes peace through common social practices, such as openness to dialogue, tolerance to differences, peaceful resolution of social conflicts, rejecting violence as a means to handle problems as well. Such qualities not only foster social harmony but also give rise to the belief that conflict may produce win-win solutions and it may not be a solely negative phenomenon.

On the other hand, in authoritarian, totalitarian, and other nondemocratically constituted states, the absence or weakness of systemic mechanisms that can alleviate social tension may easily escalate ethnic issues to the point of violent conflict. In such regimes, dominant group privileges are usually supported by local law and popular culture too, perpetuating, thus, discrimination and repression at the political level, as well as at the societal level. Hence, it is perhaps no coincidence that serious internal conflicts tend more frequently to occur in anti-democratic societies, while it can be observed that in ethnically heterogenic but democratic countries, such as Switzerland, Canada, and Belgium, no serious inter-ethnic conflicts take place. That seems to confirm a positive relationship between liberal democracy and social peace.4

Economic Distress and Unjust Distribution of National Wealth

Another factor that contributes to the occurrence of ethnic conflicts in multi-ethnic societies is economic distress and unjust distribution of national sources. When the intra-state conflicts that the UN has intervened are examined, it becomes clear that the GDP per capita in these countries is approximately $3000 according to the data by The World Factbook. Even in some countries, such as Sudan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, and Haiti, it is under this figure. Research shows that there is a strong correlation between human needs deprivation and conflict. If people are not satisfied in terms of their basic needs, they may easily become conflict-prone against other individuals and the system under which they live (see, Burton, 1979, 1990, 1997).

Aside from widespread poverty, in countries suffering from intra-state conflicts, there usually exist great gaps in the distribution of welfare among different ethnic groups. While dominant groups often get the “lion’s share” and enjoy prosperity, most minorities suffer poverty and they are entrapped in a structural violence. This relative deprivation of economic well-being in comparison with dominant groups may motivate disadvantaged ethnic groups for political mobilization.

4 On the relationship between liberal democracy and social peace, see Michael W. Doyle, “Liberalism and World Politics”, American Political Science Review, Vol. 80, No. 4, 1986; Bruce Russet, Grasping the Democratic Peace, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993; Johusa Muravchik, “Promoting Peace Through Democracy”, Managing Global Chaos: Sources of and Responses to International Conflict, (Ed.) Chester A. Crocker et al., Washington DC: US Institute of Peace, 1996.

Hence, although ethnic identity is valued in and of itself, the economic dimension is still important, for a multi-ethnic state that is characterized by widespread poverty and evidently unjust distribution of national wealth is a state where ethnic antagonisms are likely to grow. Economic well-being and perception of just distribution, on the other hand, may contribute to a sense of security, and give ethnic minorities a stake in the system. Donald L. Horowitz calls this the “distributive approach to ethnic conflict resolution”, as opposed to structural approaches based on creating a political framework. He points out that such an approach can include preferential policies aimed at raising certain groups to a position of equality through investment, employment practices, access to education, and land distribution (Horowitz, 1985: 653-681).

As a matter of fact, albeit ethnically heterogenic, the fact that there are no serious ethnic conflicts in the European Union (EU) countries where the annual GDP per capita is about $30000 on average confirms a positive relationship, among other things, between economic well-being and inter-group harmony. This can be said to be the case for many other multi-ethnic but wealthy states, such as Canada, United States, Australia, New Zealand, and so on.

Collapse of Central Authority

Sometimes ethnic conflicts may also result from the collapse of state authority. Just as serious ethnic conflicts may lead to the collapse of the state at times, the collapse, by itself, may also give rise to inter-ethnic conflicts. The reason for this is that the state, especially modern state, has many positive functions in terms of sustaining social peace and with its collapse, serious problems inevitably arise.

To be more specific, first of all, state collapse causes a local anarchy in which individuals and group find themselves in a state of serious insecurity. In the absence of a central authority, security is inevitably subjectively pursued, whereby many social conflicts occur out of it. Additionally, in-group solidarity usually increases in the absence of a central authority as individuals try to get a sense of security by clinging more to their group. Increasing in-group solidarity, in turn, exacerbates ethnocentric behaviors, that is extreme in-group favoritism and discrimination against out-groups, a social-psychological component of inter-group tension, if not conflict.

Second, the collapse of the state also results in a power struggle for governance among different ethnic groups. All major groups want to get a dominant position to run the country and pursue a more privileged status in comparison with other groups. But since different groups play the same game, their efforts inevitably clash and the power struggle among them may manifest itself in serious inter-group conflicts.

Finally, with the collapse of the state, both local and foreign investments decrease, whereby the fulfillment of people’s basic needs becomes very problematic. As a result

of that, spreading poverty, on the one hand, and pursuit of needs fulfillment with subjective methods, on the other, may create a conflict-prone structure.

In short, although it is not the only cause, the collapse of central authority may be a serious source of inter-ethnic conflicts. As a matter of fact, I. William Zartman, who studied intra-state conflicts in Africa, reached the conclusion that such conflicts were strongly correlated with state collapse (see, Zartman, 1995). Terrence Lyons and Ahmed I. Samatar, who studied the ethnic conflict in Somalia, came up with a similar conclusion in that the conflict was due mainly to the failure to restore the state authority (see, Lyons and Samatar, 1995). Likewise, the inter-ethnic conflicts occurred in the former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia after the disintegration of them in the 1990s also do not seem to be independent of the dissolution of central authority.

Historic Traumas

Alongside the interest-based considerations in intra-state conflicts, there are oftentimes obligatory psychological issues that are, in effect, tainted with irrationality too. Political, economic, historical, and military events can sometimes become so psychologies and so “stubbornly fixed” in the minds of adversaries that without an understanding of the large group psychology, it may be impossible to fully understand inter-group conflicts.

In this regard, a hidden dimension that usually plays a significant role in ethnic conflicts is historic traumas. Historic traumas refer to events that invoke in the members of a group intense feelings of having been humiliated and victimized by members of another group. A group does not, of course, choose to be victimized, and subsequently to lose self-esteem, but it does choose to psychologize and mythologize to dwell upon the event. The group draws the emotional meaning of traumatic events, and mental defenses against it, into its very identity. Members of each new generation share a conscious, and unconscious, wish to repair what has been done to their ancestors to release themselves from the burden of humiliation.

What is more, once a terrible event in a group’s history becomes a historic trauma, the truth about it does not really matter. From that time on, reality is interpreted through inner perceptions and feelings. Especially, when a new conflict situation appears and tension arises, the current enemy’s mental image becomes contaminated with the image of the enemy in the chosen trauma, even if the new enemy is not related to the original one.

A good example regarding the negative effects of historic traumas on current inter- ethnic conflicts is the case of Cyprus. A closer look suggests that the contemporary conflict on Cyprus is not an isolated issue having its own “private” life, but is a significant part of the larger Greco-Turkish issue with a thousand-year history. Despite a relatively long-time of togetherness (since 1571), in general, neither the

Greeks nor the Turks of Cyprus have ever considered themselves as members of a distinct Cypriot nation. They were, and still are, separate communities with strong emotional attachments to their respected motherland countries. Because of this “total body identification”, historical enmities between the larger Greek and Turkish nations have been transported to Cyprus. Both Cypriot communities brought past grieves and ideals of their respected nations to the island. Even the images of each side towards the other are pretty much the same as those of the motherland Greeks and Turks. Therefore, when the Republic of Cyprus was created by outside powers in 1960, there was an artificially-created state, but there was no cohesive Cypriot nation to support it (see, Xydis, 1973; Volkan and Itzkowitz, 1994).

Aside from larger Greco-Turkish hostilities, the Cypriot communities themselves have experienced many traumas at the hands of each other. The Turkish Cypriots, for instance, still remember the period between 1963-1974 as their major chosen trauma, while the Greek Cypriots similarly refer to their own chosen trauma which has started with the Turkish invasion in 1974. Past hurts affect the interactions of the two communities, as they do the formal negotiation process. This is one of the main reasons why the peace process on Cyprus, or outside it, does not go on smoothly (see, Volkan, 1989; Yılmaz, 2004).

Another example would be the ruthless attitudes of the Serbs toward Turkish, Albanian and other Muslim communities after the disintegration of Yugoslavia. For the Serbs, these communities were the descendents of the Ottomans that defeated them in Kosovo in the 14. Century. Although over six hundred years passed, the Serbs did not forget their defeat and wanted to destroy the “ashes of the Ottomans” in an effort to “purify” Serbian nationalism. This policy manifested itself in the genocide attempts in Bosnia, Kosovo, and other minority areas in the 1990s where the international community was too late to intervene.

However, it would be erroneous to claim that historic traumas directly cause ethnic conflicts. If that were the case, then ethnic groups that experienced great traumas at the hands of each other in the past would be in a constant state of struggle at present. But we know that this is not the case in light of historic facts. Nevertheless, it can be argued that historic traumas would particularly become activated under some negative conditions and further escalate a conflict after it has begun, fostering, thus, a climate of distrust, which, in turn, inhibits the search for a peaceful solution (see, Yılmaz, 2005). The implication is that ethnic conflicts ought not to be analyzed only on the ground of visible or more concrete issues, such as land, territory, or economic issues, but concrete problems should be evaluated through a historic lens and in this regard, the interplay between past and present should not be missed. In fact, if relational problems connected to historic traumas seem to define present issues and there seems little chance for progress toward a solution without overcoming them, then priority should be given to confidence building measures. Concrete issues should be handled afterwards.

The International Context

The factors that have been addressed and discussed so far are among major internal dynamics of serious intra-state conflicts. But most ethnic conflicts are also tied with international support and they may not be fully understood without taking this dimension into account.

To begin with, foreign sympathizers can contribute substantially to an ethnic group’s cohesion and political mobilization by providing material, political, and moral support. For example, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) has organized and supported oppositional activity by Palestinians in Jordan, Lebanon, and Israel’s occupied territories. Rebellious Iraqi Kurds, likewise, have at various times had the diplomatic support of the Iranian regime, Israel, and the United States. Similarly, on Cyprus, Greek Cypriots have been supported by Greece, while their Turkish counterparts by Turkey.

The most destructive consequences usually occur when competing powers support different sides in ethnopolitical conflicts. Such proxy conflicts are often protracted, very deadly, and not likely to end in negotiated settlements unless it is in the interest of external powers. When external support is withdrawn, possibilities for settlement may open up, as it happened in Angola in 2002. In Afghanistan, however, the cessation of Russian and US support in the early 1990’s led to a new phase of civil wars, fought among communal rivals for power. The country was devastated by conflict among political movements that represented the Tajiks, Uzbeks, and other minorities who opposed efforts by the historically dominant Pushtuns to regain political control. Proxy wars were especially common during the Cold War, yet by no means were limited to superpower rivalries. As it is remembered, in their 1980s war, both Iran and Iraq encouraged Kurdish minorities on their enemy’s terrain to fight from within. Ethnic mobilization is also prompted by the occurrence of ethnopolitical conflict elsewhere through the processes of diffusion and contagion.

Diffusion refers to the spillover of conflict from one region to another, either within or across international boundaries. For instance, in the last century, about a dozen ethnic groups in the Caucasus, including the Ossetians, Abkhaz, Aeries, Chechens, Ingush, and Lezghins, have been caught up in ethnopolitical struggle through the diffusion of proactive and reactive nationalism. Political activists in one country usually find sanctuary with and get support from their transnational kindred. Generations of Kurdish rebels in Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran have sustained by far one another’s political mobilizations in this way. Likewise, the Chechens outside Russia, descended from the exiles and political refugees of an earlier era, gave open support to their rebellious cousins in the Caucasus. As a rule, a disadvantaged group’s potential for political mobilization is increased by the number of segments of the group in adjoining countries, by the extent to which those segments are mobilized and by their involvement in overt conflict (Gurr, 1996: 72).

Contagion, on the other hand, refers to the process by which one group’s actions provide inspirations and guidance for other groups elsewhere. While, in general, internal conflicts are by themselves contagious, the strongest force of communal contagion tends to occur within networks of similar groups. Informal connections have developed, particularly since the 1960s, among similar groups that face similar circumstances so that, for instance, New South Wales Aborigines in the early 1960s organized freedom rides, and Dayaks in northern Borneo in the 1980s resisted commercial logging of their forests with rhetoric and tactics remarkably like those used by native Canadians in the early 1990s. In general, groups that are tied into networks acquire better techniques for effective mobilization: plausible appeals, good leadership, and organizational skills. More important, they benefit from the inspiration of successful movements elsewhere, successes that provide the images and moral incentives that motivate activists.

In sum, myriad international actors help shape the aspirations, opportunities, and strategies of ethnic groups in conflict. Thus, the nature of international engagement is a major determinant of whether ethnic conflicts are of short duration or long, and of whether they end in negotiated settlements or humanitarian disasters. Contagion may not be preventable due to advanced communication in today’s world that is largely beyond the control of any international actor, but conflict resolution efforts in intra- state conflicts certainly require a stable international environment, especially far from major-state confrontations (Yılmaz, 2005: 15-16).

⦁ INTRA-STATE CONFICTS AND THE USE OF FORCE

Despite their complexity in terms of both internal and external dynamics discussed above, most intra-state conflicts are still tried to be “resolved” by the use of force to a large extent in practice. At the national level, this is done through suppressing rebellious groups by national military and police forces, punishing or exiling the activists, in this regard. At the international level, UN and regional forces are deployed for one of three purposes: to stop immediate violence, to help recasting the institutions of the society, or to provide protection and the basic necessities of life, often through the establishment of safe havens. Depending on the requirements of a given situation, one or another of the above approaches is chosen, or they can be combined if needed.

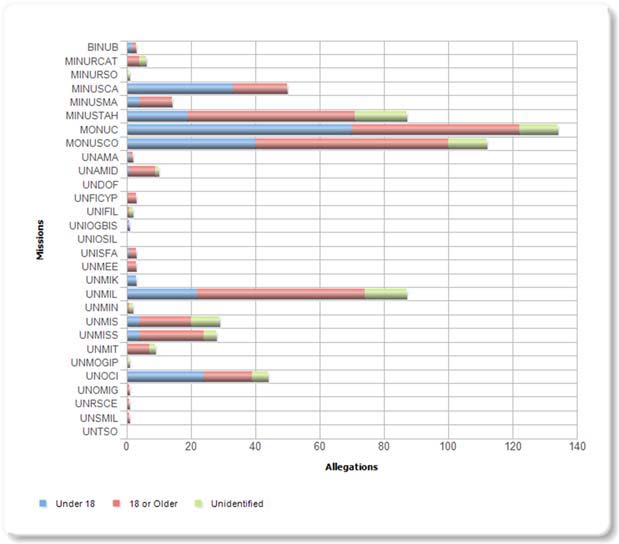

It must be admitted that sometimes a certain degree of force would be an integral part of the overall conflict resolution process in intra-state conflicts. Take international peacekeeping, for example. Especially when adversaries are engaged in mutual violence or armed clashes, peacekeeping often appears to be the most urgent strategy. Until violence is stopped, or at least managed, it is unlikely that any attempts to resolve competing interests, to change negative attitudes or to alter socio-economic circumstances giving rise to conflict will be successful. In fact, by far, thousands of civilian and military peacekeepers who have toiled over the past five decades have

been successful, in general, in keeping people alive and in preventing conflict escalation in most inter-ethnic conflicts.

By the same token, in the absence of peacekeeping forces, any group wishing to sabotage a peace initiative may find it easier to provoke armed clashes with the other side, since there is no impartial buffer between the sides which can act as a restraining influence. The absence of a suitable control mechanism may enable even a small group of people committed to violence to wreak enormous havoc, whereas the presence of an impartial third force can be an important factor for stability.

Finally, peacekeeping forces can also contribute to peace making process by:

-Monitoring or even running local elections, as in Namibia, Angola, Mozambique, the Congo and East Timor (now independent Timor-Leste).

⦁ Guarding the weapons surrendered by or taken from the parties in conflict.

⦁ Ensuring the smooth delivery of humanitarian relief supplies during an ongoing conflict, as in Somalia, Rwanda, Liberia and Sudan.

⦁ Assisting in the reconstruction of state functions, as in Bosnia-Herzegovina, El Salvador, the Congo, and Liberia.

⦁ Providing inter-communal gatherings with secure meeting places and safe escorts to and from negotiations, as on Cyprus, for instance, where the Ledra Palace Hotel, located in the UN zone in Nicosia, has been used for inter-communal meetings.

The deployment of national forces in conflict settings would be more problematic, for these forces tend to take side and act in favor of dominant groups that are in power. Thus, intervention just by national forces would indeed exacerbate tension and escalate the conflict. But on the other hand, provided that they are neutral, just, and reasonable, even national forces can be said to be functional in terms of excluding some radical wings from the essence of the problem.

However, it would be quite erroneous to assume that intra-state conflicts can be resolved through force only. These conflicts may be suppressed through force for a while, but they cannot be resolved in the conflict resolution sense. What is more, violent tactics eventually invite counter violence. Thus, rather than turn to increasingly militarized solutions – a habit that indeed pervades thinking about conflict management at the national and international level- we must more seriously consider non-violent alternatives which take account of the range of complex issues involved in violent conflicts and the people who experience them

⦁ CONCLUSION: IMPLICATIONS FOR CONFLICT RESOLUTION

Several significant lessons can be drawn from the above analyses and arguments, which can be summarized as follows:

⦁ The dynamics of intra-state conflicts are highly complex. Thus, the theories that emphasize the supposedly crucial role of a single factor are misleading and insufficient to capture the complexity of ethnopolitical conflicts. For this reason, conflict resolution strategies should also be multi-sided. In light of the above discussions, this involves finding formulas that enable expression of distinct group identities; preventing legal, structural, and cultural discrimination; democratization; economic development and relatively just distribution of national wealth; confidence building measures, as well as a stable international environment.

⦁ Particularly conflict management strategies that fail to recognize the significance of people’s ethnic identities or that fail to address the grievances that animate their political movements fail to reduce conflict. Thus, ethnic conflicts should not be merely seen as an economic issue, or a “foreign-party game”. Successful formulas ought to be found to satisfy people’s need to express their distinct group identity.

⦁ Intra-state conflicts are almost always a two or n-party game. Hence, concentrating conflict resolution efforts on one party to the exclusion of others is a no-win strategy. For durable resolution of these conflicts, all related parties must be involved in the peace process.

⦁ Intra-state conflicts cannot be coped with effectively through force only. By force, problems can be suppressed for a while, but they cannot be resolved. Ethnic groups whose subordinate status is maintained through force and repression nurture deep grievances against dominant groups, even if they may be hesitant to act on them in the short run. But in the long run, when conditions become suitable, they take action to change the status quo for the better.

⦁ Preventing or resolving intra-state conflicts is not feasible through the efforts of one actor only. Multi-level efforts must be put by several actors, domestic and international. Perhaps the best result can be obtained if various efforts by different actors can be combined. Since the problem (of ethnopolitical conflict) is many sided, and obviously there is no single formula, the wisest thing to do is to attack on all fronts simultaneously. If no one single attack has large effect, yet many small attacks from many directions can have large cumulative results over time.

REFERENCES

Berdal, Mats (2003). “Ten Years of International Peacekeeping”, International Peacekeeping, Vol. 10, No. 4.

Burton, John W. (1979). Deviance, Terrorism, and War: The Process of Solving Unsolved Social and Political Problems, New York: St. Martin’s Press.

. (1990). Conflict: Human Needs Theory, New York: St. Martin’s Press.

. (1997). Violence Explained, Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press.

Doyle, Michael W. (1986). “Liberalism and World Politics”, American Political Science Review, Vol. 80, No. 4.

Gurr, Ted R. (1996). “Minorities, Nationalists, and Ethnopolitical Conflict”, Managing Global Chaos: Sources of and Responses to International Conflict, (Ed.) Chester A. Crocker et al., Washington DC: US Institute of Peace.

Horowitz, Donald L. (1985). Ethnic Groups in Conflict, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lyons, Terrence ve Samatar, Ahmed I. (1995). Somalia: State Collapse, Multilateral Intervention, and Strategies for Political Reconstruction. Washington DC: Brooking Institution.

Muravchik, Johusa (1996). “Promoting Peace Through Democracy”, Managing Global Chaos: Sources of and Responses to International Conflict, (Ed.) Chester A. Crocker et al., Washington DC: US Institute of Peace.

Russet, Bruce (1993). Grasping the Democratic Peace, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Serafino, Nina M. (2005). Peacekeeping and Related Stability Operations, New York: Novinka Books.

The Clinton Administration’s Policy on Reforming Multilateral Peace Operations, Washington, DC: US Department of US Publication 10161, May 1994.

Volkan, Vamik D. (1989). “Cyprus: Ethnic Conflicts and Tensions”, International Journal of Group Tensions, Vol.19, No. 4.

.& Itzkowitz, Norman (1994). Turks and Greeks: Neighbours in Conflict, Cambridgeshire, England: The Eothen Press.

Xydis, Stephen (1973). Cyprus: Reluctant Republic, The Hague: Mouton.

Yılmaz, Muzaffer E. (2004). “The Political Psychology of the Cyprus Conflict and Confidence Building Measures Sustaining Peace Efforts”, Balikesir University, Bandırma İİBF Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2.

. (2005). “Enemy Images and Conflict”, Istanbul University SBF Journal, No. 32.

. (2005). “UN Peacekeeping in the Post-Cold War Era”, International Journal on World Peace, Vol. 12, No. 2.

Zartman, I. William (1995). Collapsed States, Boulder: L. Rienner.

Internet Reference

(September 12, 2019).